It was never hard to find hate and disinformation online, but it’s been much harder to avoid on X (formerly known as Twitter) since Elon Musk bought the platform in July of 2022.

Numerous independent sources have documented how prevalent dishonest and hateful speech has become on platform formerly known as Twitter since Musk purchased it last year. Just last week, the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) reported finding that X “continues to host nearly 86% of a set of 300 hateful posts after a week since we reported them.”

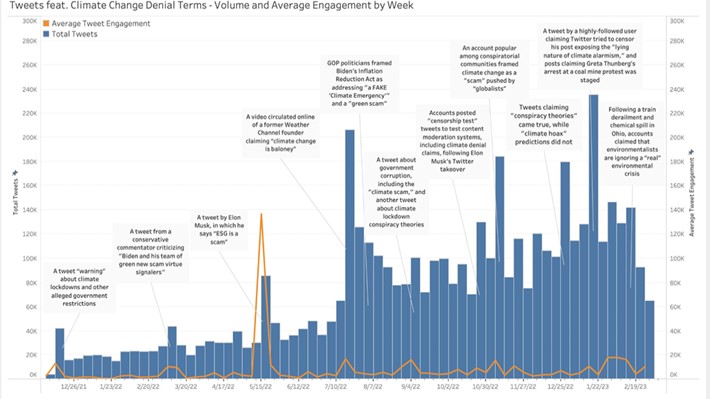

Researcher Abbie Richards found that “between December 2021 and July 2022, there were an average 30,000 climate denial tweets per week. After July 2022, that figure nearly tripled to 110,000 tweets per week.” A researcher from the University of Southern California found that the “average daily hate speech of hateful users nearly doubled” in the first six months of Musk’s ownership.

Sue the messenger

So far, Musk’s approach has not been to reinstate the Trust and Safety Council it disbanded in December of 2022. Nor has it been to strengthen content moderation policies that could help counter the disturbing trends. On the contrary, he has blamed and threatened the nonprofit organizations who’ve pointed out the problem, the fact that it’s largely self-inflicted, and the degree to which it has contributed to an approximately 60% drop in advertising revenue. Already, Musk has sued CCDH and threatened to sue the Anti-Defamation League.

Suddenly last summer

Climate disinformation and denial on social media often spikes around times of climate opportunity or action, but the trend was particularly acute on what was then Twitter during 2022. The graph above shows spikes when the Inflation Reduction Act was moving towards passage in July and August, and in the run-up to the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, last November.

During those months, researchers working with the Climate Action Against Disinformation (CAAD) coalition research unit also noticed an uptick in the prevalence of the Twitter hashtag #ClimateScam and related terms, despite the fact that more people were not engaging with this hashtag than with others such as #ClimateEmergency. (I am one of the co-chairs of CAAD’s policy group.)

Researchers still don’t understand what’s behind this spike, which cannot be explained by user behavior such as quotes or retweets. But a year later, according to one study, climate scientists and advocates are abandoning the platform, with nearly half of those who posted most on related topics becoming inactive after the final takeover.

Conflating denial and hate

“Climate denial has emerged as a new hybridized threat, merging those with vested interests in the carbon economy and those profiting from the outrage economy,” according to my CAAD colleague Jennie King of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

I saw this phenomenon myself when monitoring social media last year: after Musk’s takeover, I frequently saw posts claiming fraud in the US 2020 election and denying the safety of vaccines, the reality of climate change, the existence of transgender people, and the moon landing—in fewer than 140 characters. I am deeply concerned that this trend could have the ability to push people away from evaluating climate facts and choosing climate solutions and towards putting climate denial at the center of their identities.

Why care what liars say?

On this subject, I’m fond of quoting the great satirist Jonathan Swift: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.”

The problem isn’t just that lies move faster. In today’s world, they can shout much louder and drown out the truth entirely. Colleagues working in the CAAD’s COP research unit have found that disinformation continually outperforms verified science online, even when the latter is actively supported by platforms, for example by Facebook’s Climate Science Center.

Once a lie is out there, it’s very difficult to persuade people who’ve been convinced by it that it’s not true. CAAD’s findings suggest that climate conspiracy theories outperform the popularity and reach of any other narrative, including the good and useful science UCS contributes to public discourse.

What can we do?

Most of the content that actively disinforms X users regarding climate change causes, costs, and solutions is purveyed by relatively few users. In fact, leading up to and during last year’s COP, tweets and quote tweets from just 16 accounts amassed a total 507,000 likes and retweets! This pattern is true on Facebook and other social media platforms as well.

If Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, or other owners and CEOs really wanted to address the problem, it would be easy to check posts from these accounts BEFORE they go live on their platforms, rather than afterwards, when mere fact-checking is insufficient to undo the harm caused.

And if they won’t? We can make them. We can demand that our lawmakers pass policies that force companies to provide healthy and safe social media spaces where people can interact well and have real conversations.