It started with her right foot dropping, which caused her to fall a couple of times before she broke her ankle. When I went home to care for her, it was clear that this retired university professor and provost was no longer as mentally acute as she once had been. She cried easily, in public too, completely contrary to the “stiff upper lip” ethos of her home country of England and her war-time generation. Then we noticed slurred speech. Three months after she broke her ankle, my mum was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, also called motor neurone or Lou Gehrig’s disease) with accompanying frontotemporal dementia. With people diagnosed late in life, it can progress very swiftly—in my mum’s case, seven months from diagnosis to decease, with abilities and personality traits being shed or altered along the way.

First, she could only walk in sneakers, with a brace to lift her foot. Then she began to have trouble swallowing and needed all her liquids thickened. Then she couldn’t walk without a walker. Then she couldn’t walk at all and needed a specialized (and expensive) electric wheelchair. Then she couldn’t breathe well lying down and needed a BiPap machine to help. Then she could no longer swallow food safely and needed a gastrostomy tube (G-tube). Then she couldn’t speak intelligibly and needed assistive technology to communicate. And then, and then, and then, until she died.

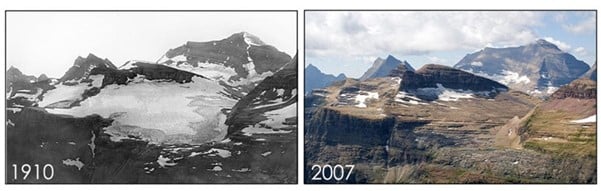

This is what climate change is like: a progressive degenerative disease on a planetary scale. We keep losing things, precious and irrevocable things. We lose a community, a homeland. A glacier. There goes a cloud forest, a warm-water coral reef, another species. Soon we’ll lose more land ice and with it, more coastal homes and cities. Then, perhaps, an ocean food web. And then, and then, and then.

The limits of adaptation

We made many efforts to support my mum’s adapting to her illness, with medicine (to date the FDA has only approved three drugs, which may slow down progression a bit and may improve daily functioning for people with ALS), with technology and surgery. Some adaptations—notably her G-tube surgery— were almost as bad as the disease itself. There were some adaptations she refused, such as a tracheostomy. Rather than prolonging her suffering, she eventually chose to abandon her life by refusing hydration and nutrition. Throughout her illness, she woke up every morning knowing that each day might mean a “new abnormal” in an ever-declining quality of life. Every day with a progressive degenerative disease is as good as it will ever get.

A similar pattern is true of climate change. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists’ framework and principles on climate resilience, “The damaging impacts of climate change will grow as the climate changes and adaptation fails to keep pace, unless societies take steps to increase their resilience through aggressive action on both climate mitigation [reducing our global warming emissions] and adaptation.” New abnormals in high temperatures, the melting of glaciers, the strength of storms—these changes are coming so swiftly. We can try to prevent wildfires in our communities by planning power outages, but then many of us can’t work or go to school or even keep our food refrigerated. Regarding sea level rise, there are places we can build sea walls, which can buy time but worsen impacts for neighboring places. There is surely a limit to the number of times any given community can rebuild after a major hurricane or can adapt to the level of chronic flooding they will endure. People are already abandoning their homes in Louisiana, Maryland, and Alaska, to name just a few places. Recent research from Climate Central projects that by 2100, areas now home to 200 million people around the globe could fall permanently below the high tide line. Today is as good as it will get.

The importance of community

Technologies could only help my mum so much. What really supported her at the end of her life were people: my brother Tom, who moved across the country and became her full-time caregiver; Miss Bessie, her supremely competent and kind home health care provider; the hospice nurses and volunteers; her neighbors, friends, and other children. Together we drew a circle of care that allowed my mum to live as well as she could in her own home throughout the progression of her disease, and to die there in privacy and some dignity.

Climate adaptation and resilience professionals also talk about community: they emphasize the importance of rising to the challenge together and describe social cohesion as a “secret weapon” in the fight for equitable climate resilience. Policymakers are recognizing this too. In both the American Families Plan and the American Jobs Plan, President Biden is proposing investments, not just in technological and built infrastructure such as roads and broadband, but in people, care, and community: in community colleges, Historically Black Colleges and Universities and other minority-serving institutions; in childcare and in home health care workers like Miss Bessie; in paid family and medical leave.

Avoiding maladaptation: don’t do stupid stuff

Once we’d received my mum’s diagnosis and prognosis, at no point did our family consider moving her bedroom upstairs or replacing her shower stall with a soaking tub. We stopped buying any of her favorite treats she wouldn’t be able to chew. Instead, we invested in a transfer seat for showering and silky pajamas so she could be turned more easily in bed. In short, we chose not to do stupid stuff. We didn’t close our eyes to the progressive nature of her disease but tried our best to anticipate it and to prepare her and her care circle for the next stage, the next challenge. Any failure to look ahead to her changing needs would have heightened her discomfort, and perhaps would have broken our family maxim: we would do things with our mum, not to our mum.

This is how people and policymakers need to think about climate change. I have a witty colleague who says she knows a neat trick to turn a two trillion-dollar infrastructure investment into a six: ignore climate impacts. Ignoring the likely future climate means doing stupid stuff, such as not building to withstand the changes we can predict with confidence. That’s why it’s so important to replicate and expand policies such as California’s Climate Safe Infrastructure Working Group and the climate provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act.

The US needs to stop inadequately scrambling from one climate-worsened disaster to the next. Instead, we must reduce the dangers and the impacts before people suffer. And at every political level, our country needs policies and practices that do things with communities at risk, rather than for or to them.

Causes and cures

At present, medical science has identified a few genes that cause an estimated five to ten percent of ALS cases. We don’t yet know what factors or combination of factors cause the other 90 – 95%. When my mum was diagnosed, we knew from her prognosis that there was no chance for a cure in what remained of her lifetime—and even if there were, it would not be likely that dead nerves would regenerate and restore her abilities. It will be a long, hard slog to find a cure for this disease.

With climate change, we’ve had a solid theory of the cause since the 19th century work of Fourier, Foote, Tyndall, and Arrhenius. Schoolchildren can understand it: when we extract or burn fossil fuels for transportation, heating or cooling, to generate electricity, to raise cows and sheep for food, or we burn forests, we add heat-trapping gases to our atmosphere. There, they trap excess heat. It’s that simple.

Because the theory of human-caused climate change has been confirmed with multiple lines of evidence, we know the cause. The “cure,” or at least the effective treatment, has been obvious for a long time: we need rapidly to switch the global economy to renewable energy, decrease our consumption of meat, reduce our consumption in general. We’ve let the disease progress so far that there will be some things we can never retrieve. But if we slow the pace of climate change, we can still save much and increase the chances of adapting successfully to our strange new world.

Stages of grief and hope

We must all find ways to grieve this cascade of losses and the many to come. I’ve never been a fan of the well-known “stages of grief.” In my experience the emotions of grief do not follow an orderly sequence but are turbulent, chaotic. I work with good scientists, so sustaining denial is out of the question for me, but anger, bargaining or wishful thinking, depression, guilt, shame, acceptance, occasionally relief, swirl through and bewilder me.

It’s not much use to be angry at a malign fate, so I didn’t feel anger at my mother’s illness. I couldn’t feel angry at medical science or her team of expert care-givers—I knew people were working as hard as they could with the resources they had. But with climate change we know both the cause and the treatment. We have both in our grasp but have delayed action because we’d have to pay some now instead of much more later. Our wanton, willful avoidance enrages me more than anything, especially when I think of the malign fate we are creating for my mum’s grandchildren and all future generations.

I combat my symptoms of climate grief in many ways. When I catch myself thinking wishfully, I listen to one of my hard-headed and warm-hearted scientist colleagues. When I feel depressed, I get silly with my family or play the piano. When it snows in New England where I live, or the trees blaze brilliant red and gold at the “right” time in the fall, I breathe with relief. I try to turn my anger into outrage: an emotion that motivates me to go out and target my rageful energy at those who obstruct climate progress.

A dear colleague who attended the most recent in-person United Nations Framework on Climate Change Congress of the Parties, in Madrid in December 2019, was outraged at the obstruction, yes, but also heartened to hear from people from all over the world who had struggled and defeated various tyrannies. They gave her hope that we will prevail. There are simply too many millions of us around the world for us to lose. And making change feels like it takes forever until it doesn’t, and then it too can progress swiftly.

It’s true that we will not recover all we’ve lost. But unlike ALS, we can live with the disease of climate change—we will just need to value different things. The world as we know it doesn’t work for far too many people and other species anyway, so we have an opportunity to build quality of life while we transform towards sustainability. While the climate is as good as it will get for a very long time, our world is not. We can slow the progression of our global disease and build a world we can adapt to, thrive in, and live in with joy. Like my mum, we can raise a glass to the future.