Over the years, my family and I have driven up, down, and across California’s Central Valley on road trips from our home in the Bay Area. On each trip, I’ve marveled at the Valley’s climate (hot and arid), its landscape (flat), the scale of its agriculture (massive), and the bounty advertised on handmade signs along the road (almonds! honey! tomatoes! strawberries!). What’s harder to see from the road are the people who work under conditions that are frequently dangerous to produce that bounty: the region’s farmworkers.

With jobs that already carry nearly 35 times the risk of heat-related death than the average job in the United States, farmworkers in California’s Central Valley work under often-grueling conditions that are expected to worsen with continued climate change. As part of our series on climate change in the Central Valley, this post focuses on the risks climate change and extreme heat pose to farmworkers and other outdoor workers in the region.

Farmworkers in the Central Valley

The Central Valley encompasses all or part of nearly 20 counties in California. As my colleague Marcia described in a post earlier in this series, despite the fact that these counties represent less than 1 percent of nation’s farmland, they produce about a quarter of the nation’s food and an even larger share of its fruits and nuts. Across the Central Valley, there are more than 35,000 farms and nearly 6 million acres of harvested land, which is roughly the area of Vermont.

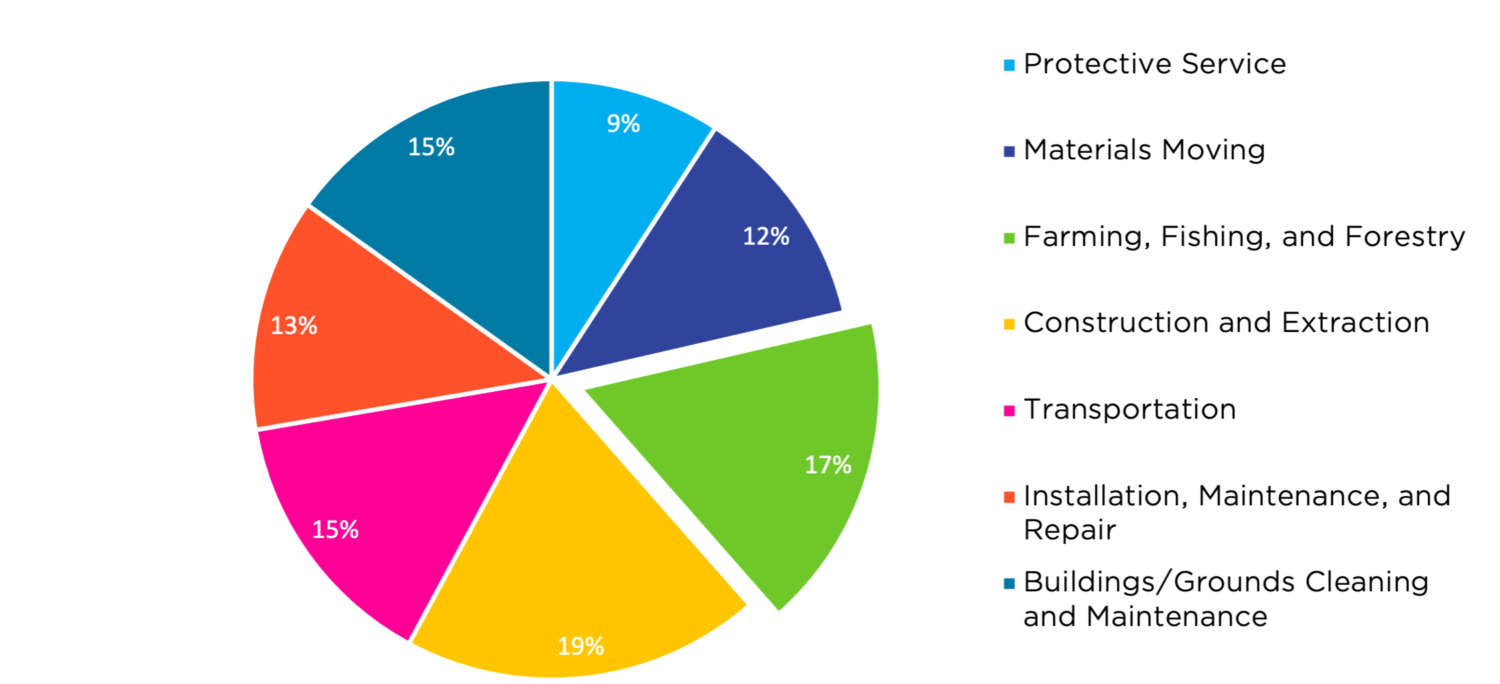

Given the scale of the Central Valley’s agricultural production, it’s not a surprise that it relies on the labor of thousands of farmworkers. While estimates of the number of farmworkers in the U.S. are highly uncertain and vary widely depending on the source, data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey indicates that there are an estimated 146,400 people working in farming, fishing, and forestry jobs across the Central Valley, which represents about 17 percent of all outdoor jobs in the region (see pie chart below). In the counties with the highest percentages of outdoor workers in farming, fishing and forestry jobs—Colusa, Glenn, and Tulare Counties—about 40 percent of outdoor workers work in these occupations (see maps below). While these come from an official source, they are unlikely to be capturing the entire farming workforce in the Central Valley because an estimated 75 percent of the state’s farmworkers are undocumented.

These are exhausting, back-breaking—and too often life-threatening—jobs. Further, farmworkers are often exploited, performing this dangerous work for insufficient wages and with few legal protections. Workers in farming, fishing, and forestry jobs in the Central Valley earn, on average, about $20,000 per year, which is about 40 percent less than the average worker in California. Given that more than 90 percent of California’s farming, fishing, and forestry workers identify as Hispanic or Latino, it’s clear that Central Valley workers in these occupations may be marginalized both because of low incomes and/or ethnicity.

Climate change will make the hot Central Valley even hotter

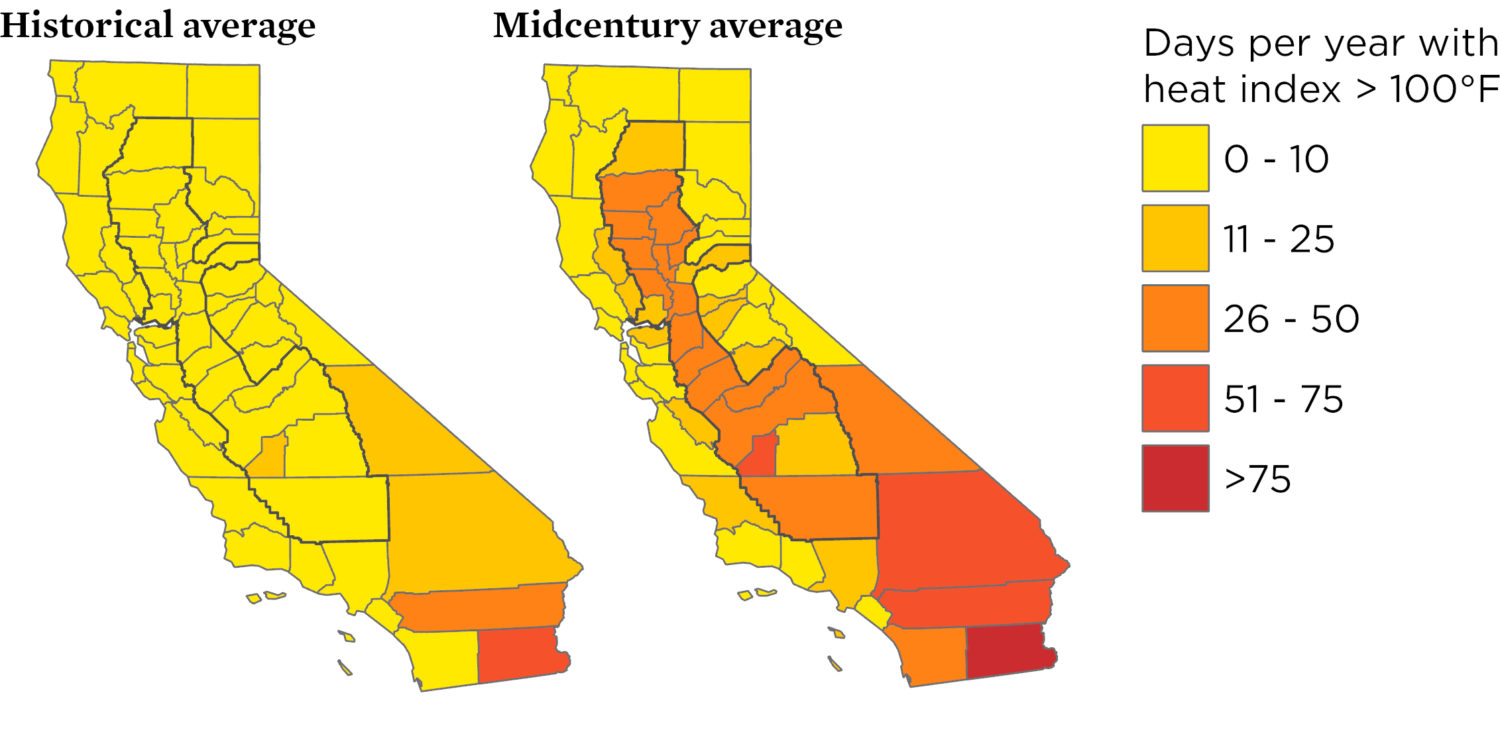

Of the many challenges that farmworkers and other outdoor workers face in the Central Valley, among the most dangerous is regular exposure to the region’s heat. Historically, Central Valley counties have averaged about 45 days per year with a heat index above 90°F and about 6 days per year with a heat index above 100°F. Meanwhile non-Central Valley counties in California have averaged about half as many 90°F days—about 22 per year—and four days per year with a heat index above 100°F. What that means is that on average, outdoor workers in the Central Valley experience more days of extreme heat each year than outdoor workers elsewhere in California.

Why does that matter? Extreme heat exposure can cause a range of problems, ranging from dizziness to heat stroke, which can be fatal. Agricultural workers who are repeatedly exposed to extreme heat exhibit both persistent dehydration and increasing rates of acute kidney injury as temperatures rise.

Climate change will worsen heat exposure for the Central Valley’s outdoor workers. By mid-century, with no action to reduce global emissions, Central Valley counties would experience more than 30 days per year with a heat index above 100°F, meaning about one month per year of such conditions (see the bar chart and maps below). If we continued on a path of increasing emissions through late century, the Central Valley would see nearly 60 such days per year. On the other hand, rapid action to reduce emissions and limit warming to 2°C or less would cap the number of these dangerously hot days at about 22 per year—still a significant increase from what workers have historically experienced but less than half of what would be expected with no action to reduce emissions.

Protecting workers from extreme heat

The frequency of days with a heat index above 90°F or 100°F is significant because outdoor work poses risks to workers’ health, lives, and livelihoods under such conditions. California is one of the few states in the U.S. that has statewide standards in place for protecting outdoor workers from extreme heat. While the data above is for heat index (a combination of temperature and humidity), in California, employers are required to implement high heat procedures when the temperature is at or above 95°F. Those procedures include ensuring that employees have access to shade and water; are able to communicate with their supervisors; are assigned a buddy; and are given a 10-minute rest break every two hours.

California’s worker-protection requirements when it comes to extreme heat don’t match exactly with what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has recommended. For example, NIOSH recommends using a combination of temperature and humidity as the basis for adjusting how much time workers spend in the heat whereas California uses temperature on its own without considering humidity. Humidity can make “real feel” temperatures much higher than the thermometer reading.

That said, California’s requirements are consistent with the fundamental idea that workers need water, shade, and increasing amounts of rest as temperatures rise. And there are some indications that California’s rules are working, albeit with room for improvement. A recent study found that occupational heat-related injuries in California have declined by about 30 percent since the standards took effect in 2005. Such data will undoubtedly prove useful as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration embarks upon the process of creating a national heat safety standard for both indoor and outdoor workers. Similar legislation in Congress is named for Asunción Valdivia, a father and a farmworker who died after working a 10-hour shift.

It’s important to note that workers may be hesitant to report and attend to symptoms of heat illness for a variety of reasons. In some instances, workers are paid “piece rate,” which means that they’re paid by the piece or by the pound for the produce they harvest. If you’re already struggling to make ends meet, taking time off during a hot day could mean harvesting less and, as a result, getting paid less. Moreover, undocumented workers may fear deportation if they speak up about their symptoms and the need to rest. Truly comprehensive heat protective standards for outdoor workers would therefore need to ensure that workers do not lose wages or risk retribution simply because they’re trying to stay healthy on the job.

Central Valley farmworkers face more than just heat

Heat is just one of the many threats faced by farmworkers in the Central Valley. For example, California’s statewide pesticide application rate is more than 4.5 times the national average, and rates for some Central Valley counties are even higher. Toxic pesticides are dangerous for farmworkers under any circumstances, and protective clothing worn while applying pesticides can make workers even more susceptible to heat illness. And as UCS fellow Carly Phillips will discuss in the next post in this series, outdoor workers in the Central Valley are regularly exposed to wildfire smoke. On their own and together, heat, pesticides, and smoke present serious threats to worker health.

We’re heading toward the glorious peak of strawberry season in California. So the next time you pick up a pint of the state’s strawberries, or the next time you grab a handful of our delicious California almonds, take a moment to thank the Central Valley’s farmworkers by encouraging Congress to act to protect workers across the country.