A new analysis out today and led by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) reveals a significant amount of critical infrastructure along US coastlines at risk of disruptive flooding today and in the near future as sea level rises, potentially affecting millions of coastal residents. We unpack the results of our analysis in a new report—Looming Deadlines for Coastal Resilience—and a slick new interactive mapping tool. Here, I’ll summarize why we did this analysis, what we found, and how the nation can address the risks we’re facing.

Climate risks to critical coastal infrastructure are flying under the radar

Sea level rise is a climate change impact that doesn’t charge into our lives the way a wildfire or a hurricane might—exploding in size and causing catastrophic damage in a short period of time. But over the last century, sea level has risen enough that coastal communities are starting to feel its effects.

In Norfolk, Virginia, the razing of a public housing development due to coastal flood risks has forced former residents of Tidewater Gardens to fight to secure their right to inhabit new affordable housing. Down the coast, in Charleston, South Carolina, sewer overflows due to tidal flooding have sent unhealthy, partially treated wastewater into nearby waterways.

Even without storms or heavy rainfall, high tide flooding driven by climate change is accelerating along US coastlines. It is increasingly evident that many critical infrastructure assets along our coasts—such as power plants, wastewater treatment plants, and schools—that were safe when constructed are now at risk of being regularly inundated with seawater.

Hundreds of coastal infrastructure assets at risk this decade

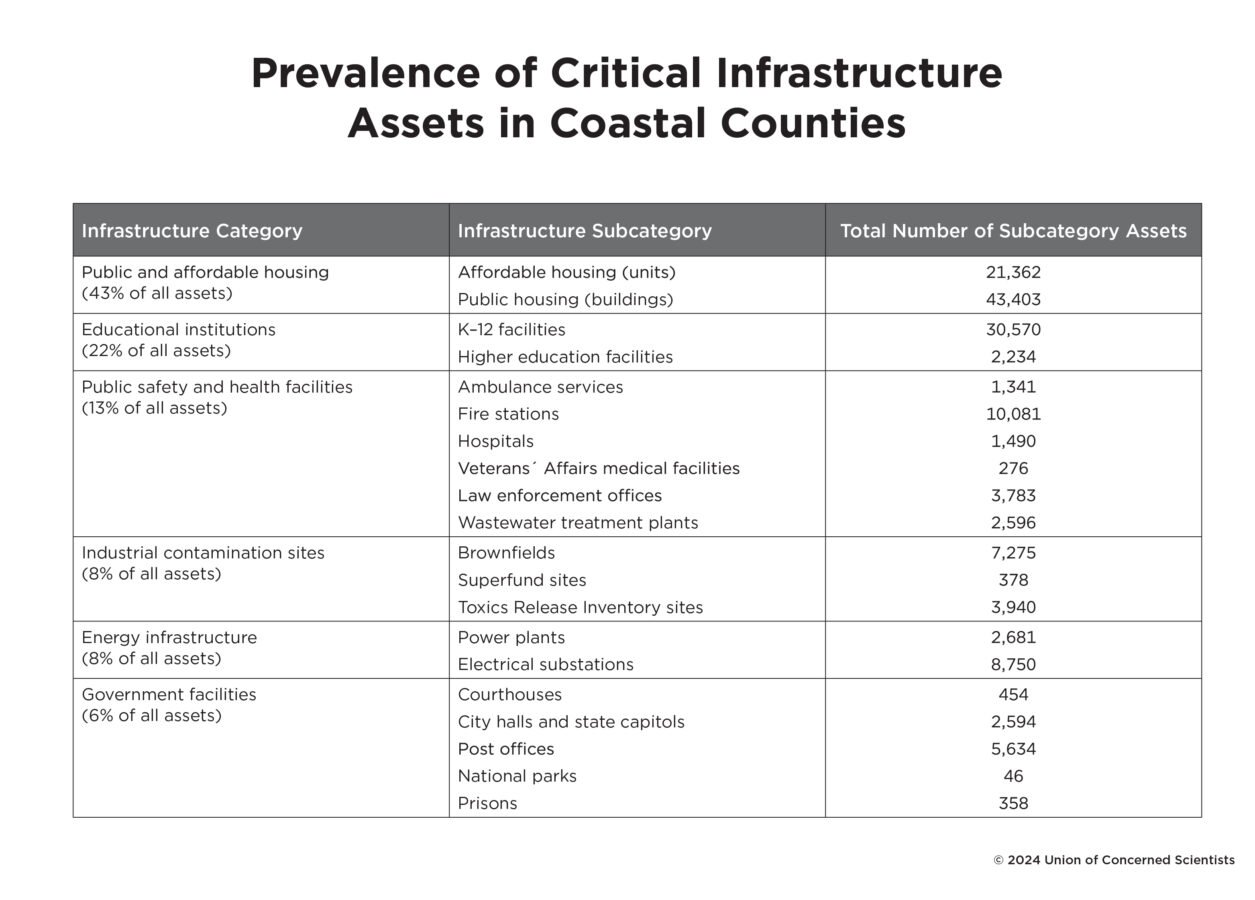

To determine where and when coastal infrastructure would be at risk of flooding, we first mapped out areas along the coast that would flood 2, 12, or 26 times per year under a range of different amounts of future sea level rise. We then overlaid those maps with a dataset of infrastructure located along the coast, which included six different categories of buildings and services, from public and affordable housing to schools, hospitals, fire stations, and industrial contamination sites.

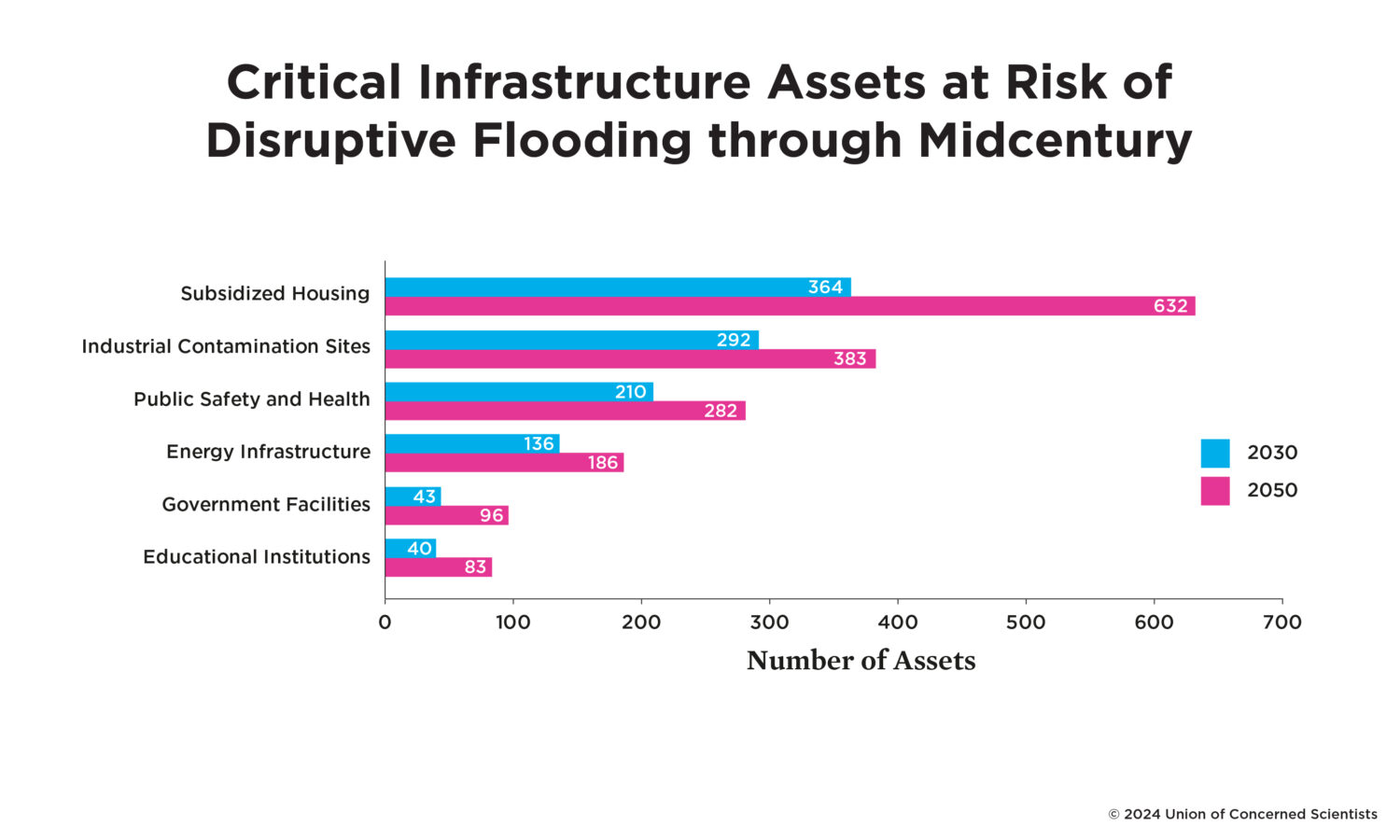

Over the course of this decade, our data show a sharp increase in the amount of infrastructure exposed to two or more disruptive flooding events annually, from 904 assets nationally in 2020 to 1,085 assets nationally in 2030. Those assets currently serve communities that are home to 2.2 million people—roughly the population of the fourth biggest city in the country, Houston, Texas.

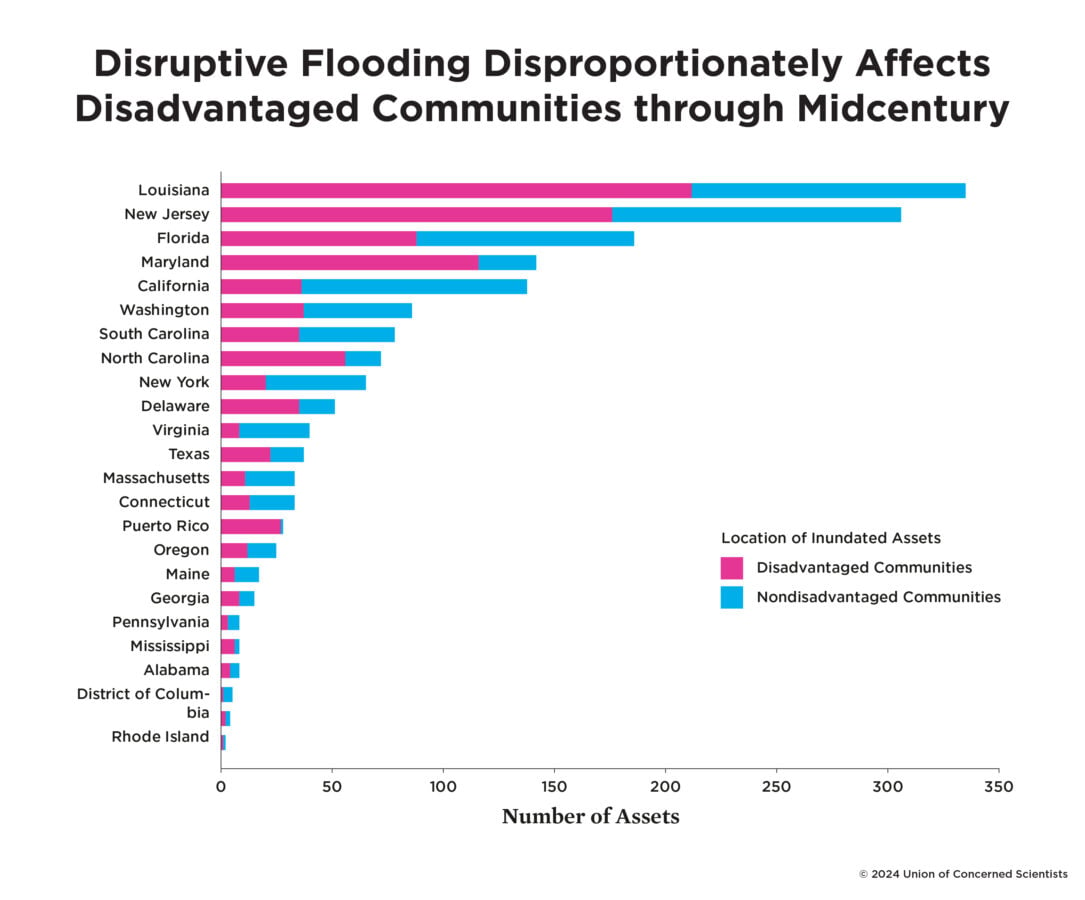

Some communities will be more affected than others. Atlantic City, New Jersey, for example, is among the hardest-hit communities in this time frame, with 44 public and affordable housing facilities at risk of flooding twice annually by 2030. In the town of Raceland, Louisiana, 16 public housing buildings, an electrical substation, and a sheriff’s office are all in danger of flooding twice annually by the end of this decade.

Of note, communities designated as disadvantaged by the federal government contain nearly twice as many at-risk assets per capita as nondisadvantaged communities. Additionally, communities in which five or more infrastructure assets are at risk are home to a disproportionately higher percentage of Black residents compared to the national average. This greater potential for disadvantaged communities to be affected by flooding is poised to exacerbate existing, unaddressed inequities caused by environmental racism and toxic pollution.

Major risks within the next 25 years

By 2050, with a medium sea level rise scenario in which sea level rises by roughly one foot, 1,662 critical infrastructure assets are at risk of flooding an average of twice annually. Overall, public and affordable housing, brownfields, electrical substations, wastewater treatment plants, and fire stations are the types of infrastructure with the most facilities at risk.

In this midcentury timeframe, disadvantaged communities contain, on average, about twice as many at-risk infrastructure assets per capita as nondisadvantaged communities, and more than 70 percent of the public housing at risk is located in disadvantaged communities. Moreover, disadvantaged communities with at-risk infrastructure are home to significantly higher percentages of people who identify as Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, or Native American than the national average. In Maryland, for example, 82 percent of the assets at risk are in disadvantaged communities, where 41 percent of the population identifies as Black or African American, compared with roughly 32 percent of the population in the state as a whole.

Our collective choices now will determine fates later this century

With higher emissions and greater warming, higher amounts of sea level rise late this century become more likely, mostly because there is greater potential for ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica to shrink, adding more water to the ocean. With such scenarios, more present-day infrastructure would be exposed to persistent flooding, with potentially grave consequences for the continued livability of coastal communities. Conversely, lower sea level rise scenarios are more likely if global emissions decrease substantially, and future warming is limited to 2°C or less. With lower sea level rise scenarios, less infrastructure would be at risk late this century.

We found that under a low sea level rise scenario, roughly 3,500 critical infrastructure assets would flood twice annually by 2100—a challenge, to be sure, and a substantial increase from the amount of infrastructure at risk today. Under a medium scenario, roughly 6,500 assets would flood with that frequency. And under the high scenario, that figure jumps to 15,081.

The low, medium, and high scenarios result in profoundly different implications for the level of adaptation required, for state- and community-level consequences, and for the number of people whose daily lives could be affected.

Funding and leadership are needed now to build coastal resilience

The risks to vital infrastructure and services that millions of people depend on will grow as the global sea level rises in the coming decades, with wide-ranging implications for public health, safety, education, and well-being, and for coastal ecosystems and ways of life. This predicament creates a profound and urgent responsibility for policymakers and public and private decisionmakers to take protective action now, working together with communities. In our report, we outline six recommendations decisionmakers should act on:

- Use science and innovation to plan for near- and long-term risks

- Scale up public and private sector funding for infrastructure resilience

- Reduce historical inequities and prevent future harms

- Protect affordable housing; open just pathways to retreat

- Start informed, flexible, adaptive planning now for later-century potential outcomes

- Cut heat-trapping emissions to limit the pace and magnitude of sea level rise

You can read more about each of these recommendations in the report itself or in report co-author Rachel Cleetus’s blog post.

There is a narrow window of time for federal, state, and local policymakers to provide funding and resources and for local decisionmakers to use this backing to make transformative changes to their communities that would help them to withstand future flood risks. Our analysis shows that the scale of the challenge is daunting, but it also points to actionable, science-informed steps that can and must be taken to protect vital infrastructure and services. Investments in resilience, equitably shared, can help build a safer, fairer future for all.