California is burning (again). As a climate scientist living in California, the state’s wildfires over the past few years, while startling, have not been particularly surprising. This is, after all, what scientists have been predicting for a very long time. But there’s a profound difference between being clear-headed and understanding of predictions and feeling existential nausea because this is the reality we have created for ourselves and our children.

Our hearts ache for those who have lost their homes to wildfire or have had to evacuate and live with uncertainty. They ache as we drive on winding roads through forests devastated in years past by fires, by bark beetles. They ache as we imagine the majesty of Yosemite Valley cloaked in smoke and closed indefinitely, thousands of potential visitors unable to look up in wonder at Half Dome.

For my children, who have grown up in this state, it is normal to see ash raining down from metallic yellow skies in July. It is normal to have recess indoors because the air is unfit for little lungs. And while we seek out pristine forests for vacations, they see it as normal to drive through acres of blackened trees. Knowing that this is their normal, knowing that the future does not look much brighter gives me a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach.

Inspired by all that heartache, let’s take a step back and put this year’s fire season into perspective.

Are fires like this the new normal for California?

As of today, there are 11 active wildfires burning in California. The largest of these, the Mendocino Complex Fire, which is made up of the River and Ranch Fires, is over 290,000 acres in area, making it the largest wildfire in the state’s modern history. That means that the two largest fires in the state’s modern history have both occurred within the last eight months–a troubling signal. Farther north, the Carr Fire, in the Redding area, is affecting over 160,000 acres and has destroyed over 1,000 structures.

Calling the current state of wildfire in California a “new normal” isn’t quite right because this particular point in time is, unfortunately, part of a long-term trajectory toward increasingly devastating fires. Globally and for the western US, wildfire trends are very clear. Whether measuring by the length of the fire season, the area burned, the number of large fires, or a variety of other metrics, it is clear that wildfire activity has been increasing since about 1980. On a global basis, a study from earlier this year found that the length of the fire season has increased by nearly 20% since 1979.

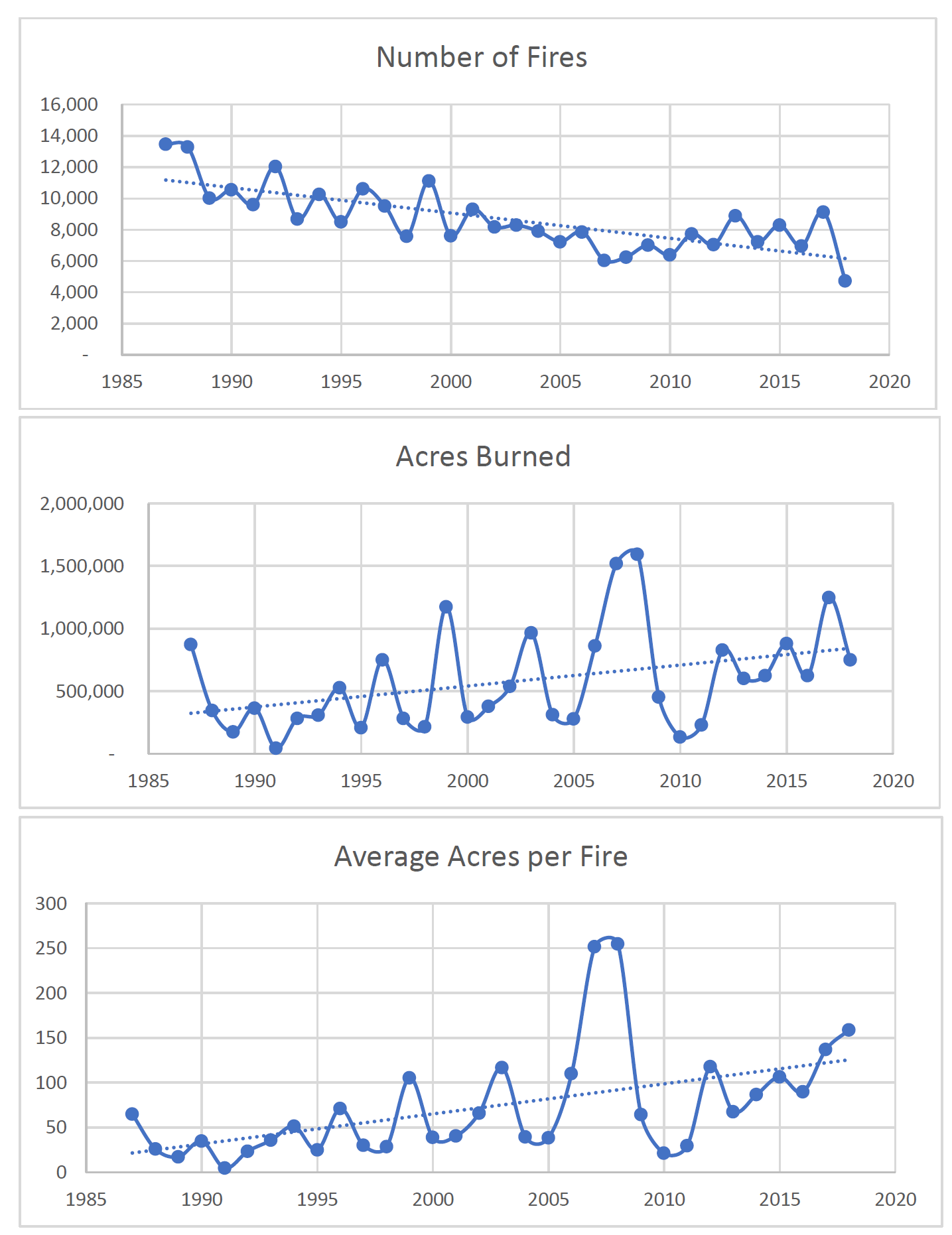

In California, interestingly, data provided by CalFire shows that the number of fires in the state has been declining since the 1980s, but the number of acres burned has been slowly increasing, which means that the average fire size has increased over time.

It’s important to note that these statistics are only one measure of how destructive wildfires are. While 2017 does not stand out in this data as particularly exceptional, it was the most destructive season on record with over 10,000 structures damaged or destroyed, which speaks to the fact land use and development play strong roles in determining overall wildfire risk.

Human-caused climate change plays a role in driving wildfire

There are many factors that contribute to overall wildfire risk, some climate-related (such as temperature, drought, soil moisture) and others not (such as vegetation type, land use, and fire suppression practices). Because of the range of variables involved in determining wildfire risk, attributing trends in wildfire activity to human-caused climate change is more difficult than for other types of extreme events such as heat waves or coastal flooding.

Recent studies, however, have attributed over half of the recent trends in the aridity of wildfire fuels and forest fire areas directly to climate factors. In particular, warming temperatures–particularly in spring and summer–earlier snowmelt, and drying soil are contributing to heightened wildfire risk across the western US.

This summer has been a scorcher for California. Nearly statewide, both average and daily minimum temperatures have been well-above average, and many cities have seen their high temperature records broken. Warmer minimum temperatures in particular are changing the pace at which wildfires are growing.

While there has not yet been any research to specifically attribute California’s hot weather this summer to human-caused climate change, in general, such extreme heat has been linked to climate change. High temperatures dry vegetation, which then becomes fuel for wildfires. So while we can’t say for certain yet that human-caused climate change is responsible for the devastating wildfires in recent years, it’s clear that warming temperatures are increasing the likelihood of such events.

More extreme heat on the way for Californians

The Carr Fire in Northern California broke out just days after the area was under an excessive heat warning issued by the National Weather Service. In the week leading up to the onset of the fire, temperatures were running as high as 110 degrees F–up to 10 degrees above the historical average.

California is bracing for another round of extreme heat this week, with broad swaths of the state expecting temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter. Coupled with the seasonally-typical lack of rain and extremely dry vegetation, these conditions could pose additional wildfire risks, tax our already weary firefighters and present health risks to residents already weary of this season’s heat and smoke.

The future of heat and wildfire

As temperatures continue to rise in the coming decades, the risk of wildfire is expected to grow. Wildfire is far from the only danger of rising temperatures, however. Extreme heat can cause a wide range of impacts to human health and society, from increased heat mortality to deterioration of asphalt roadways.

The excessive heat warnings for California this week alert residents of the increased potential for heat-related illnesses, particularly for children, the elderly, and those without access to air conditioning.

In Shasta County, California, where the Carr fire is burning, a preliminary analysis by UCS suggests that the number of extreme heat days in the county is poised to rise as global temperatures continue to warm. While wildfire risk increases as humidity decreases, direct heat-related impacts to human health tend to increase when hot temperatures and high humidity occur together. Looking at the heat index—a combination of heat and humidity that the National Weather Service relies on when issuing heat advisories—the number of days of extreme heat in Shasta County is poised to increase significantly in the coming decades.

With a business-as-usual emissions scenario, the number of days with a heat index above 100 degrees Fahrenheit will go from an average of 4 days per year historically in Shasta County to 17 days per year by mid-century and over 30 days per year by the end of the century. That’s an additional two weeks to a month of conditions that will pose additional health, infrastructure, and wildfire challenges to the region.

About 38,000 people in Shasta County were forced to evacuate because of the Carr fire, and while many of them have since been allowed to return to their homes, continued heat and dangerous levels of air pollution make living conditions far from safe.

What can we do to prevent extreme heat and wildfire

Climate change is here. It’s now. But we are not powerless to help those who are in need now or to help our future generations. May we pour our hearts into helping those affected, and may we pull ourselves out of the pit of climate despair to advocate for the policies that will be critical to limiting future harm. Increasing renewable energy and decreasing coal use, bringing clean vehicles to the forefront of our transportation system, and implementing proactive, science-based forest management practices are all part of creating the kind of future we want for ourselves and our children.

Preliminary analyses provided by Juan Declet-Barreto.