Across the western U.S., the physical and emotional scars from last year’s record-breaking wildfire season are still fresh. No one wants to imagine another season like last year’s, but with the dry season well underway and zombie fires popping up within areas that burned just months ago, it’s time to start asking ourselves what’s in store for the months ahead. So here’s what we know so far about what this year’s western wildfire season might bring (tl;dr: buy that air purifier now before they’re out of stock.)

We’re still recovering from 2020 wildfires

Before we dig into what’s in store this year, let’s recap a bit. Last year’s wildfire season was before the election, before the deadliest stretch of the pandemic, and before any vaccines were available. So much has changed since last year’s flames died down that it might feel like a distant memory.

In 2020, many western states saw their most extensive wildfire seasons on record. Nationwide, about 10.3 million acres burned, which is roughly double the area of Massachusetts. More than half of those acres were in California and Oregon alone. It was a devastating year for other states as well: Colorado saw its most active wildfire season on record, for example, and in Arizona more acreage burned in 2020 than in 2018 and 2019 combined.

With so much damage and destruction, perhaps it isn’t surprising that recovery from last year’s fires is still very much underway. The damage continues to limit access to treasured trails and parks in Northern California. Damaged trees and homes in California and Oregon are still being cleared. And with more than 10,000 structures destroyed and an estimated 1,200 premature deaths due to wildfire smoke exposure in California alone, an untold number of people are still coping with the loss of homes or loved ones. Meanwhile, in Arizona, this year’s fires have already claimed homes and necessitated evacuations in communities such as Bagdad and Minnehaha.

With such a long way to go to recover from last year’s fires, it’s daunting to be heading into another season of fire.

It’s been dry. Really dry.

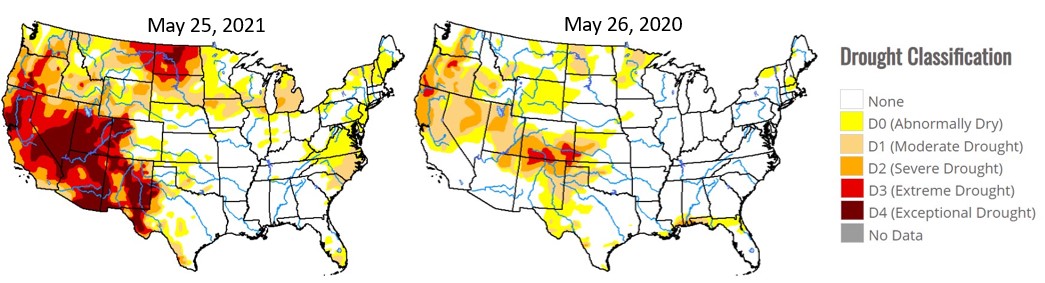

Heading into last year’s wildfire season, much of the West was either abnormally dry or experiencing moderate drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. But after a paltry winter rainy season, drought conditions have become much more severe and much more widespread. Much of Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Utah are currently experiencing extreme or exceptional drought—the two most severe drought classification categories.

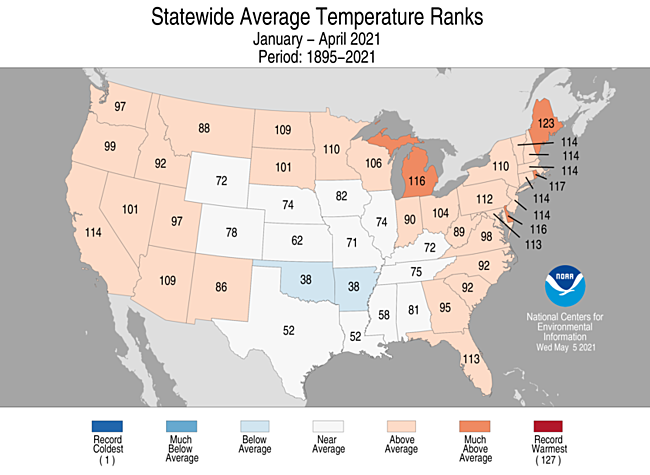

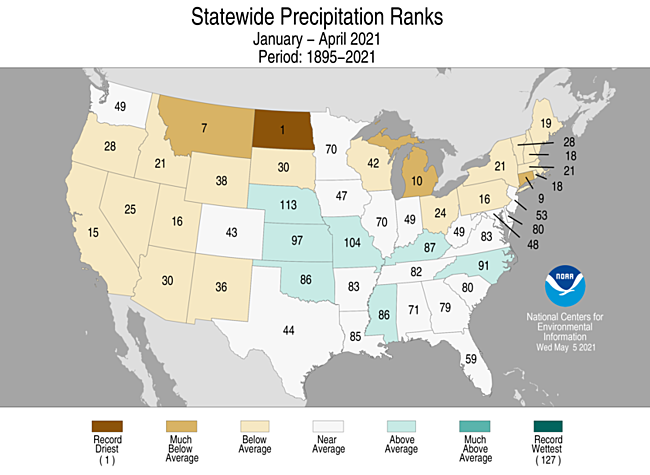

Looking at the leadup to those late-May drought maps, we can see the much of the West experienced warmer-than-average temperatures and below-average amounts of precipitation during the January-April period.

In California, we depend on the slow melt of snowpack for about one-third of the state’s water. The snowpack fills the state’s reservoirs and provide water for agriculture for drinking during the dry season. The amount of snowpack this spring was well below normal and since mid-May snowpack has been at about 10% of what’s normal. As of June 1, there is basically no snowpack left. All our major reservoirs are significantly below their average volume for this time of year. And the seemingly and understandably perennial battles for water between the agricultural industry and those trying to protect ecosystems have reared up.

Next door, in Arizona, extreme heat and drought have prompted fire restrictions that prohibit campfires—and in some cases even smoking—on state lands, and scientists are reporting troubling signs that even drought-tolerant ecosystems are stressed.

It’s like it’s 2015 again, but worse.

What does this all mean for wildfire this year?

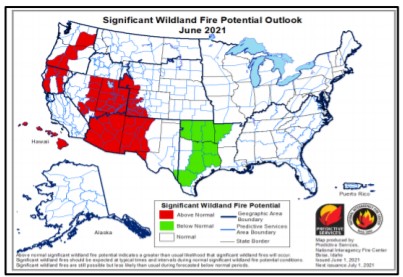

The warm temperatures and exceptionally dry conditions this winter translate into forecasts for above-average levels of wildfire risk across much of the West this year. The southwest monsoon, which brings moisture and thunderstorms from the Gulf of Mexico to Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of the Rockies, is expected to bring relief to those areas in July, but until then, wildfire risk will be running high.

As fire risk abates for the desert southwest, however, risk is expected to ramp up across California, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and Washington. While the overall patterns of risk this year are similar to what was predicted in last year’s seasonal outlook, coastal California and the Sierra Nevada stand out as having a higher level of risk this year than last.

That much of the West will have above-normal wildfire risk over the next few months is not a surprise given that warmer temperatures and a lack of precipitation cause vegetation to dry out and become ready to burn. Since the 1970s, climate change has been responsible for more than half of the drying out of vegetation in western forests. So the conditions we’re currently experiencing are consistent with what we expect in a warming world.

What’s different this year?

No two wildfire seasons are the same, of course. Aside from the physical climate conditions being somewhat different this year, here are a few additional factors that could make this year’s wildfire season different from those in the recent past:

- COVID-19

When wildfire season kicked off last year, we were mere months into the pandemic. With broad availability of vaccines in the U.S., a much better handle on the virus’s transmission patterns, and some clear guidance in place for conducting evacuations during a pandemic, we can head into the 2021 wildfire season with a greater understanding of what we need to do to prevent COVID-19 flareups. All that said, it is critical that we proceed with some level of caution until vaccination rates are up and we know more about COVID-19 variants and mutations. - Lightning sieges

Part of what made the 2020 wildfire season so devastating in California was the truly insane lightning siege in early August that ignited several of the fires that grew to record sizes. Dry lightning events like this are rare in the state—last year’s was the first I’d experienced in my 12 years of living in the Bay Area—so experiencing another one this year would be very unusual. That said, last year’s siege led to the devastation it did because conditions were so hot and dry. When such conditions are in place, as they are this year, all it takes is a single spark. - Budget surpluses

After months of deep concern about the impact of the pandemic on state budgets, many western states, including Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington, are finding themselves with large, unexpected surpluses.

In California, Governor Newsom has dedicated a portion–what some have called a “game-changing amount of money”–of the state’s estimated $76 billion surplus to wildfire prevention and resilience. The funds will go toward both firefighting equipment and land management efforts aimed at reducing wildfire risk.

The situation is very different, however, in Arizona, where state legislators would like to use the budget surplus as a justification for making the largest tax cuts in decades. The reduced state revenue from taxes would translate into less funding for cities in towns throughout the state. Prescott, Arizona, where communities bump right up against forested areas, is expected to receive $1.7 million less per year from the state because of the tax cuts—money that could be spent on building wildfire resilience in a place with high wildfire risk.

These surpluses present a one-time opportunity for states to invest heavily in building wildfire resilience in communities, and many are advocating that they should do just that. Making such investments now would likely pay off down the line in the form of fewer lives at risk, fewer structures destroyed, less land needing post-fire remediation, and less infrastructure at risk. While some surplus-related investments in wildfire resilience wouldn’t necessarily be felt immediately, others, such as hiring additional firefighters, could. - Federal policy landscape

While one-time surplus spending could provide a much-needed boost to wildfire resilience efforts, what we ultimately need is sustained investments in preparedness and prevention. The Biden Administration’s recently announced plans and commitments to reducing heat-trapping emissions signal a shift in the direction that the climate action winds are blowing. For instance, the USDA recently released a new strategy document that calls for removing much more vegetation from federal forest lands. And the Administration recently allocated $1 billion to FEMA’s BRIC program, which is intended to cover preparation for a wide range of disasters.

Additionally, the announcement of Biden’s American Jobs Plan, which focuses on upgrading the nation’s infrastructure, contains an impressive 15 mentions of climate and makes clear connections between the state of our infrastructure and our vulnerability to climate-related disasters. As the hard work of translating this ambitious plan into implementable policies progresses, we’ll be working to ensure that proposed infrastructure investments are made with future climate risks—including future wildfire risks—in mind. Critically, those investments must address the vulnerabilities of our power grid to climate-related disasters such as those exposed in Texas just a few months

This year’s wildfire season may be another rough one. But with state and federal investments in building wildfire resilience, we have the potential to ensure that when lightning strikes, the West is ready.