I didn’t walk into the movie theater last week, popcorn in hand, expecting Twisters, a summertime action movie about “taming” tornadoes, to be a movie about climate change. And to be clear, at no point did Twisters actually mention climate change. But beneath the cowboy hats, the quotable one-liners, and the impressive special effects, the film mirrors two climate change realities:

- Communities are deeply unprepared for worsening extreme weather; and

- There is a growing industry attempting to use data to profit from the risks and consequences those very communities face.

Sure, I left the theater having been entertained. But I also left feeling deeply unsettled. Here’s what Twisters has me thinking about.

The connections between climate change and tornadoes are complicated

Unlike other types of extreme weather, such as heat waves and hurricanes, the influence of climate change on tornado activity is unclear. That’s in part because there are a number of challenges to studying tornadoes. They’re small in scale relative to hurricanes, for example, which means they’re more difficult to detect in observational records. They’re more difficult to simulate in climate models because there are a number of different factors—such as high wind shear and the presence of warm, moist air—that have to come together for a tornado to form. And there is a lot of variability in the number of tornadoes from year to year.

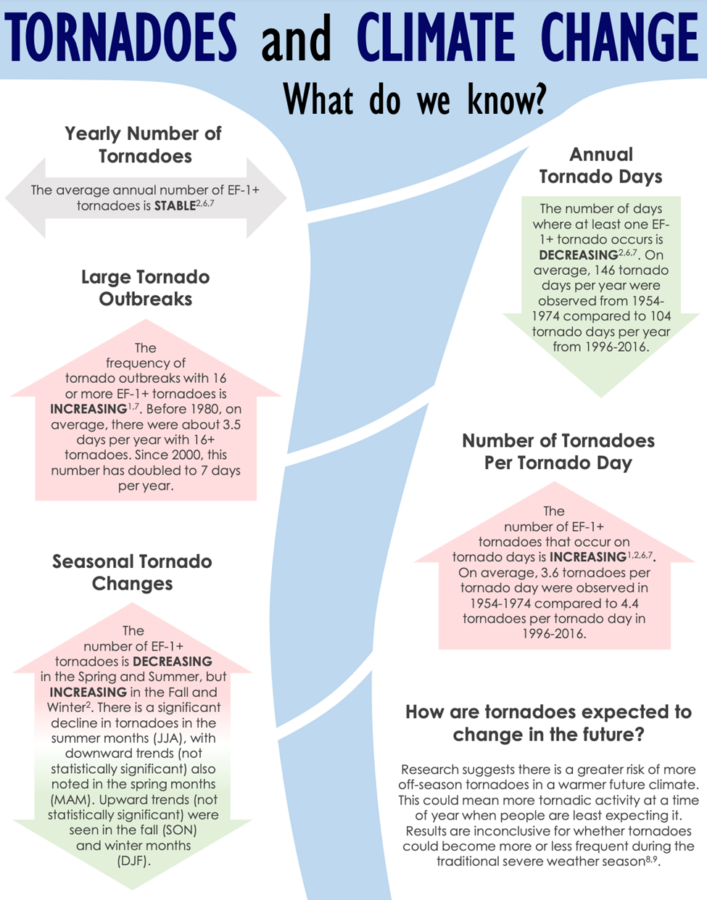

But recent studies suggest that patterns of tornado activity—if not the annual average number of tornadoes—have changed over the last several decades. These changes, summarized by NOAA in the graphic below include:

- An increase in the number of tornado outbreaks with a high number of tornadoes

- An increase in the number of tornadoes in the fall and winter

- A decrease in the number of tornadoes in the summer

- A decrease in the number of tornado days per year

- An increase in the average number of tornadoes occurring on tornado days

- An eastward shift in the region in which tornadoes often occur

But climate change is also increasing the likelihood of conditions that are conducive to tornado formation. Perhaps most importantly, climate change increases the likelihood of high temperatures as well as the amount of moisture in the air.

So when, in Twisters, the protagonist’s mother says something to the effect of, “It seems we’re getting more and more of these storms and floods,” the writers could not have simply inserted a reply such as, “You’re right, Mom, and what you’ve witnessed is backed up by a Dodge Ram-sized trove of climate data.”

But they could have written any number of other replies, and it might have planted a little seed in moviegoer’s minds to grow into a post-viewing conversation.

A missed opportunity to get people talking about climate resilience

A movie about extreme weather that gets rolled out in thousands of theaters at the height of Danger Season but doesn’t mention climate change is a missed opportunity to get people thinking and talking about climate change. (But here you are reading this, so maybe a movie doesn’t have to explicitly mention climate change to get people engaged?)

Opinion polling shows that while nearly three-quarters of US adults think global warming is happening, only about one-third of adults discuss climate change at least occasionally or hear about it in the media on a weekly basis. Add to this the decades-long greenwashing campaigns companies like BP, ExxonMobil, and Chevron have waged, and the result is that the public ranks dealing with climate change as one of the nation’s lowest policy priorities.

Fossil fuel industry deception and policymaker inaction have inhibited progress on climate change for decades, and until it becomes something people are regularly discussing and demanding action on, it’s difficult to see that changing. So every movie, every TV show, every book, magazine, and newspaper article about extreme weather should be an opportunity to get people talking.

“Taming” tornadoes is a fantasy; building resilience to them is not.

In Twisters, the protagonist’s main goal is to save lives, homes, and communities by “taming” tornadoes, which she thinks can be done by injecting individual storms with a sequence of chemicals that will essentially cause them to fall apart. There’s some reality to the suggestion that people can modify the weather through fairly widely used methods like cloud seeding.

But there have always been tornadoes. There have always been hurricanes. There have always been wildfires. These are some of the many ways the climate system releases and redistributes energy. We can’t prevent every extreme event, and we certainly can’t shut down extreme events as they’re unfolding, as the movie suggests. But we can be better prepared for them.

We can reduce heat-trapping emissions, which will limit the future worsening of extreme weather events. We can develop strong early-warning systems that enable people to get to safety when an event is expected. And we can invest in programs like FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program to help communities prepare for and better withstand disasters. Estimates suggest that implementing tornado-proofing measures—such as building to stricter codes and using anchors and metal clipping to connect a home’s wood framing to the roof—could cost just $1.50-$2.00 per square foot for new home construction.

To that end, Twisters felt to me like a rallying cry to boost disaster preparedness and recovery resources at every level, from the individual to the global. There’s a sense in the movie that only individuals working apart from our systems and structures can keep communities safe from storms, or help them recover in their wake, a la the amazing Cajun Navy. I agree that we do collectively need to take care of each other. And I was left thinking about the need for more structured support: community-level disaster mitigation plans, the rapid deployment of on-the-ground recovery teams, and the network of resources that’s needed to get people back on their feet over the long haul.

Also: cowboy hats (who says climate resilience can’t also be stylish?).

When it comes to risk analytics data, who benefits?

If Twisters has a villain, it’s not the tornadoes themselves, and nor is it climate change. Rather, it is the company trying to collect tornado data, so they can swoop in after a strike and profit off of the housing losses in affected communities. Various forms of such disaster capitalism have been documented in the aftermath of events such as Hurricane Katrina, earthquakes in Haiti and Italy, and the COVID-19 pandemic. We must be diligent about who is benefiting in the weeks and months after a disaster.

While what’s depicted in Twisters is essentially disaster capitalism, it’s important to acknowledge that in real life, there’s a growing number of for-profit companies that sell climate risk data—often developed in-house using proprietary methodologies—that purport to help everyone from individual property owners to major insurance companies better evaluate their level of climate risk. On one hand, the holders (or potential holders) of financial assets need to better understand the risks climate change poses to those assets. On the other, without transparency on how these data are being developed, there are many potential pitfalls to its use. Companies could, for example, underplay uncertainty in the climate models they are using, or present a false sense of precision in their data. Either one could lead to poor decision making among users of that data. Moreover, the cost of the data could be a barrier to people and communities with low incomes, leaving them without information that could save them money, their homes, or even their lives.

All of that made for complicated feelings as the movie’s true villain came into focus.

As a summer blockbuster, Twisters likely gives moviegoers what they’re looking for in the moment: an entertaining story, dramatic visuals, and, hopefully, a couple hours in a nice, cool movie theater on a hot summer day. But I hope viewers also walk out of the theater and take a moment to think about—maybe even talk about—what wasn’t said.

When it comes to climate change, we have no choice but to face our fears and to ride ‘em.