Extreme heat and heatwaves are growing more frequent and more severe because of climate change. That often brings to mind images of people trying to catch some shade under a baking hot sun or city kids cooling off in a fountain while their parents sweat on the sidelines.

While climate change is making our days hotter, the fingerprints of climate change are even clearer for nighttime temperatures than for daytime temperatures. Nights are warming more and faster than days, which is concerning because warm nights deprive our bodies and minds of the chance to cool off, and that has consequences for our health.

Here’s what we know about changing nighttime vs. daytime temperatures and why it matters.

What’s been observed

Nearly 30 years ago, scientists used data from more than 2,000 weather stations around the world to determine whether and how daytime and nighttime temperatures had changed between 1951 and 1990. What they found was that across the stations they analyzed, both minimum (that is, nighttime) and maximum (that is, daytime) temperatures had, on average, warmed. But minimum temperature had warmed by 1.4°F whereas maximum temperatures had warmed by 0.5°F. In other words, nights warmed more than days in that time range. Those changes effectively decreased what’s known as the diurnal temperature range, or the difference between the maximum and minimum temperatures within a day.

Since that study three decades ago, many studies have affirmed the globally averaged pattern of greater nighttime warming than daytime warming and we now have a more complete sense of the magnitude of the change since 1901. We now know, too, that this pattern doesn’t hold everywhere and differences in nighttime vs. daytime warming vary across the globe. Some regions, including North America, show clear and consistent signals of greater nighttime warming than daytime warming whereas others—such as Australia—don’t exhibit clear trends.

Across the United States, average minimum and maximum temperatures are 1.4°F and 1.1°F warmer, respectively, than they were during the first half of the 20th century, according to the Fourth US National Climate Assessment.

Why are nights warming faster than days?

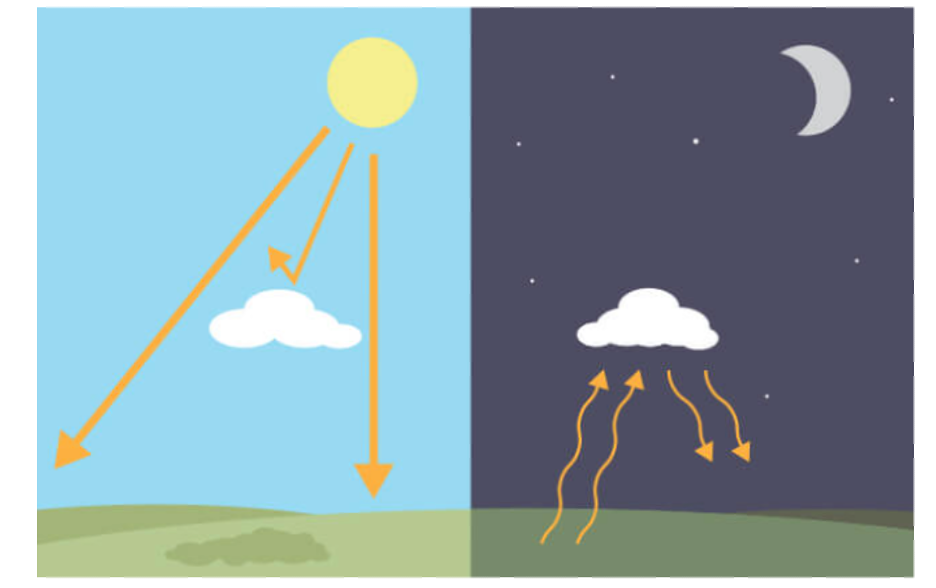

In a nutshell, the answer is clouds.

Global warming is causing there to be more cloud cover over land areas because a warmer atmosphere can essentially hold more moisture. The types of clouds that have increased—specifically thick, precipitating clouds—reflect sunlight back into space during the day and have a cooling effect. But they absorb and re-emit heat back down to Earth’s surface at night, acting like a blanket. By increasing cloud cover, climate change is acting like the blanket you don’t need in a stuffy room on a hot, summer night.

All of that adds up to nights experiencing more warming—and faster warming—than days.

A recent study showed that in the parts of the globe where cloud cover, humidity, and precipitation have increased, nighttime warming is outpacing daytime warming. The opposite is true as well: in parts of the globe where cloud cover, humidity, and precipitation have decreased, daytime warming is outpacing nighttime warming. Other factors, such as the amount of moisture in soils, can influence these patterns too.

How much more likely are hot nights given climate change?

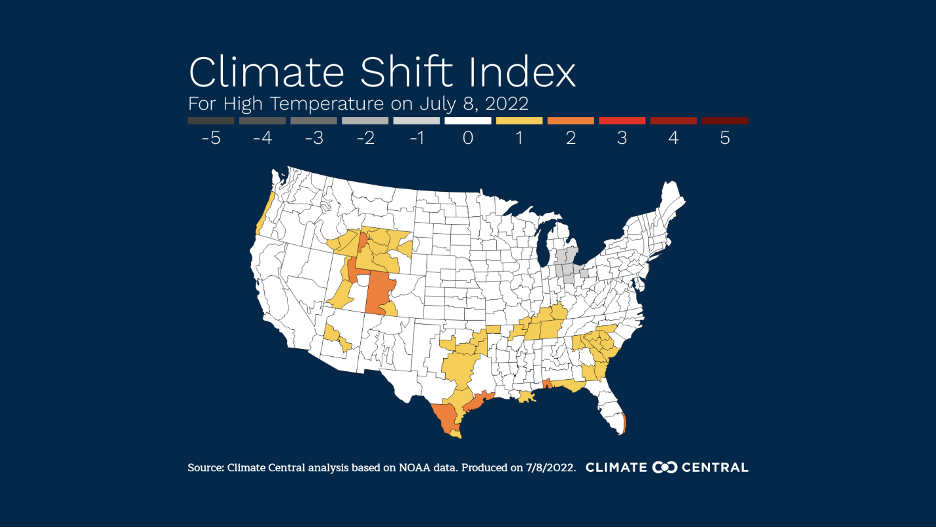

Our friends at Climate Central have developed a tool that shows how much climate change is affecting temperatures in the US on a daily basis. On most days, you can see just how much more climate change is affecting nighttime temperatures than it is daytime temperatures.

Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index (CSI) looks at the forecast for today’s high and low temperatures (and the forecasts for the next couple days) and calculates whether climate change is making whatever temperatures we’re experiencing more or less likely. An index of zero means that climate change is not making the forecasted temperature any more or less likely—basically, it’s in line with what we’d see without climate change. Index values of one to five indicate that climate change is making the forecasted temperature between one and five times more likely.

I’ve been checking out the CSI maps daily since the tool launched, and they consistently show climate change having a greater impact on nighttime low temperatures than on daytime highs.

For example, on July 8, 2022, we can see that climate change is making the forecasted high temperatures in places like Texas and Colorado slightly more likely, with the yellow and orange colors indicating an 1-2x increase in likelihood:

But if we look at the day’s forecast for the nighttime low temperature, we can see that climate change is making those temperatures as much as five times more likely across large swaths of the southern half of the country—that’s the darkest red color in this map:

It’ll be interesting to see if that continues to hold true during seasons other than summer because studies have also shown that the diurnal temperature range varies between seasons and that winters tend to be warming faster than summers.

Why does it matter?

Humans have come to expect that cooler nighttime temperatures provide relief from hot days during a heat wave. Anyone who has spent time in extreme heat has felt how a cool night gives our bodies a chance to cool down after a blazing hot day. But when nights remain hot, health risks and heat-related deaths rise because our bodies are unable to shed the extra heat they’ve accumulated during the day. Imagine a construction worker or a farmworker working day in and day out in triple-digit heat. If they can’t get relief at night because nighttime temperatures are high, too, they’re at higher risk of persistent dehydration, heat-related illnesses, injuries, and death.

High temperatures on their own put strain on our bodies, but also measurably affect our ability to get sufficient sleep, which comes with its own set of harms to cognitive performance, attention, memory, etc. Elderly people and people in low-income countries are particularly prone to sleep loss when it is hot.

Hot nights can be exacerbated in urban areas because of the urban heat island effect. Cities tend to be hotter than the surrounding area on any given day because they contain relatively fewer shade-providing trees and an abundance of heat-retaining materials and surfaces, such as asphalt, cement, and pavement. The extra heat cities absorb during the day is then re-radiated at night, keeping air temperatures in urban areas up to 22°F warmer than their surroundings.

Moreover, nighttime air conditioning releases additional heat into the city environment. During heat waves, the urban heat island effect can be particularly harmful, as it reduces or eliminates the cooler hours when people can get physical and mental relief.

The health risks associated with hot nights are particularly high for those without access to air-conditioning or for whom the choice of turning on the air-conditioning presents difficult financial trade-offs. People of color and people with low incomes are particularly at risk, as they disproportionately live in hotter urban environments or have less financial flexibility to keep the air conditioning running. Those conditions often stem from the fact that decades or centuries of systemic racism have resulted in chronic underinvestment in the health and wellbeing of people of color and their surrounding environments. When heat puts untenable strains on the electric grid and causes blackouts or when power is shutoff preemptively to mitigate wildfire risk, the inability to cool off at home at night can affect millions of people.

Avoiding a future of dangerously hot nights

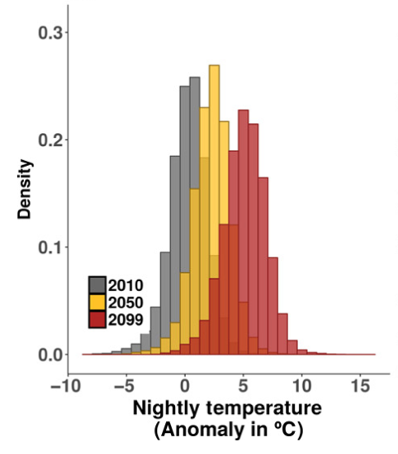

Climate models show the frequencies of high daytime and nighttime temperatures are both expected to increase in the future as heat-trapping emissions rise, but the models don’t agree on whether the diurnal temperature range with increase or decrease over the United States. Just looking at nighttime temperatures, in high-emissions scenarios, average nighttime temperatures across the US would increase by roughly 9°F (5°C) by late century, which is on par with the overall warming the nation is expected to experience in that scenario.

But science also shows that the frequency and intensity of events that involve both hot days and hot nights depends on the emissions choices we make in the coming decades and how effectively we are able to limit future warming to 1.5°C or 2°C. In fact, global temperatures are expected to cease rising within a few years of when we reach net-zero global emissions.

Cutting our emissions quickly and steeply would help to keep our nights comfortable and safe. Heatwaves and hot nights claim hundreds of lives in the US every year, so we must also be putting appropriate supports in place that would help people stay safe and healthy even on sweltering nights. Those supports can and should take many forms, but to name a few, city planners and public health departments must continue addressing the problem of urban heat islands; grid operators and utilities must continue to push for greater reliability while also making a concerted shift to clean energy sources; and states should adopt policies preventing utilities from shutting off a person’s electricity—even if they’re behind on their bills—when there’s a heat wave.

It’s often said that heat-related deaths are preventable. To truly prevent them in the face of warmer days and hotter nights, we need to take action.