Writer Maya Angelou once said, “You are the sum total of everything you’ve ever seen, heard, eaten, smelled, been told, forgot – it’s all there.”

Likewise, our health is the sum of all that we breathe and drink, all that wears us down, all that nourishes and heals us, and all that connects us to one another, whether we are neighbors or distant relatives.

Transportation is only one part of our lives, and clean, affordable, and just transportation options can help our communities live healthy and thrive. Yet, for decades, the expansion of highways and fossil-fueled vehicles have harmed many communities through displacement, toxic air pollution, and high economic costs… often all at the same time.

What’s more, these are often communities of color and low-income communities. Decades of research have shown that these communities, often called frontline or environmental justice (EJ) communities, are already saddled with the cumulative impacts of hazardous facilities, water contamination, climate impacts, and many other stressors to their health.

What are cumulative impacts?

Cumulative impacts is a science-based concept and analytical framework that encompasses “the combined chemical and non-chemical stressors on a community’s health, well-being and quality of life.” It is a concept rooted in EJ community experience that recognizes that no one faces chemicals or stressors one at a time from one source at a time.

As it relates to transportation, this helps highlight that folks living near a busy highway are breathing in more tailpipe pollution, facing higher risks of car crashes in their neighborhoods, and suffering from decreased quality of life and economic growth—all at once. In places like the Allendale neighborhood of Shreveport, LA, the proposal for a new highway builds on the harms of past highways and a longer history of segregation and disinvestment. In the Africatown neighborhood of Mobile, AL, the I-10 bridge project threatens to divert truck traffic to a community that’s already a hotspot for industrial pollution, poor air quality, lack of access to grocery stores, forceful displacement of residents, and economic disinvestment.

Too often though, we set policies that treat each issue in a vacuum. Air pollutants are regulated individually. New transportation projects are evaluated project by project. This can make issues appear smaller than they are in reality, experienced all together. In the end, who is looking out for communities as a whole? Who is tallying up all the harm and is able to say, “enough is enough”?

We need a holistic approach.

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

– Audre Lorde

NEPA and Transportation 101

In the transportation world, one of the scant references to cumulative impacts comes from a requirement of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

NEPA requires federal agencies to assess the direct, indirect, and cumulative environmental effects of proposed federally funded projects, and consider potential alternatives, prior to making final decisions. It has been called the “Magna Carta” of federal environmental laws, and is a vital tool to ensure community voices are heard and that their perspectives are part of decision-making processes.

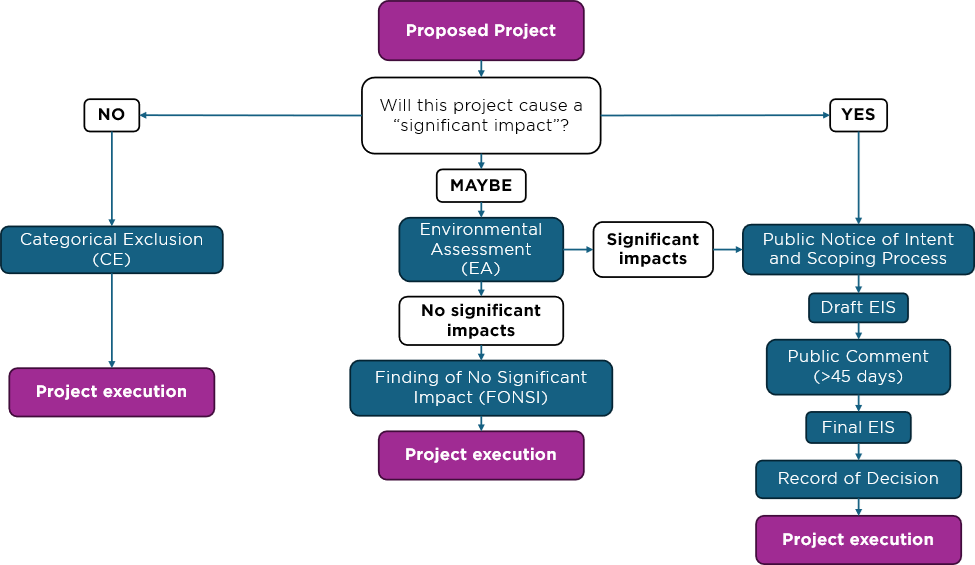

NEPA applies to any transportation project using federal funding, whether it’s adding another lane to a highway, a train station expansion, or a new bus rapid transit line. Not all projects have the same level of review though. There are three possible ways a project goes through the process:

- Categorical Exclusion (CE): Projects that meet a set list of federal criteria that do not involve significant impacts, such as striping a bike lane or adding a bus shelter, sail through the process with reduced paperwork. This includes 92% of state department of transportation (DOT) projects.

- Environmental Assessment (EA): Projects with an uncertain environmental impact require a “concise public document” detailing the proposal, alternatives, and an initial assessment of its impacts. Projects are then either given a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) or are moved onto the full assessment process if there are significant impacts. 7% of state DOT projects go through the EA process, and most are given a FONSI.

- Environmental Impact Statement (EIS): Projects with a significant impact require a detailed assessment of a project’s impacts and alternatives, with requirements for public engagement. The agency then issues a Record of Decision explaining the reasons for the final project decision.

In addition to NEPA, a multitude of other federal protections also require consideration of cumulative impacts. For example, in 2017, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) found that the Texas Department of Transportation violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, based on the disparate impacts of the location of the Corpus Christi Harbor Bridge Project through the historic Black Hillcrest and Washington-Coles neighborhoods. In its findings, FHWA notes that the severity of cumulative impacts must be assessed between different project alternatives.

Largely though, federal agencies underestimate their existing authority and legal responsibility to consider cumulative impacts.

Federal protections set a baseline… and much more is needed

Without a doubt, federal reviews help protect communities and give an important opportunity to weigh in on processes that shape our world. In fact, the Freeway Revolts of the 1960s were one of the major factors in the nearly unanimous passage of NEPA in 1969. With the Trump administration, even the existence of these protections is under attack. And still, there are ways where it has not gone far enough in protecting communities from harm.

First, federal protections are broad enough that state DOTs have extensive leeway in applying them. As our partners at Transportation for America say, “the NEPA process is more like a standardized test for state DOTs, except instead of being graded on their answers, they’re graded on how well they’ve filled in the bubbles.” In seven states, DOTs are allowed to grade their own tests through a loophole in federal law known as “NEPA assignment.” This has led to cases in Texas of splitting big, harmful projects such as I-35 into multiple, smaller proposals that got FONSIs and didn’t require as detailed of a review.

As one transportation advocate put it, “it’s all vibes, little metrics.” An EIS can easily overlook localized air pollution impacts and historical levels, which would highlight the health impacts of highway expansion on EJ communities. It can also be based on flawed traffic modeling that ignores traffic increases from induced demand and can even get away with claiming that highway expansion will improve air quality (ridiculous!). For more on the scientific basis for rethinking highway expansion, see Freedom to Move p.48.

Second, public input often feels like a checkbox exercise, and is not always required. Cumulative impacts analyses in EAs do not require a formal public process, even though public input is encouraged in practitioner guidance. The scope and depth of a cumulative impacts analysis is determined on a case-by-case basis, and it’s left to the whims of agency staff to take community input into account.

Lastly, federal protections like NEPA don’t require agencies to choose a project that has the least impact, only to inform and try to mitigate them. In the end, even if a project is found to harm a community that is already bearing the burdens of many cumulative impacts, many regulations leave a gaping hole in legal protection for a community against a bad project. In a world where powerful political interests push for highway expansions that harm communities, these protections are even more important.

Cumulative impacts policies need your support across the country

We are facing alarming attacks on science and environmental justice and need to hold the line on the progress we’ve made while keeping the vision for a healthy and equitable future. When transportation and environmental justice advocates work together, we’re more powerful.

Minnesota is one place where this is happening. The recently introduced 2025 Highway Justice Act (SF 817) includes an expansion to the state’s cumulative impacts law to include major highway projects that run through EJ communities. Just like an incinerator or a chemical plant, highway expansions all too often add to the cumulative impacts communities already face.

The bill would require that any major highway project with substantial adverse impacts to EJ communities would require either entering a community benefits agreement, changing the proposal, or halting project development. This is grounded in the grassroots work of organizations like Our Streets, who have been organizing community members for years for streets and neighborhoods that are vibrant places for people to live, work, and play.

“What we need is a people-centered approach to transportation.”

– Joe Harrington, Our Streets

And while we are fighting harms, we still need to support what nourishes us. Projects that benefit communities – like a dedicated bus lane that both brings economic development and air quality benefits, or a new bike or pedestrian path that increases safety and provides access to everyday places in your community… those are projects that everyone can advocate for to help those weighed down with cumulative impacts feel a little lighter.