Last week, the Federal Highway Administration finalized an important regulation–the greenhouse gas performance measure. UCS along with more than 100,000 members of the public have written in support of this national rule that will gather the scattered and incomplete data counting greenhouse gas emissions into a unified standard so local, state, and federal transportation authorities can make informed decisions.

Currently, only 24 states and the District of Columbia have laws requiring them to set targets and track their greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. Given that transportation is the sector of the economy that contributes the most to the climate crisis in the US, and our transportation sector is the highest emitting transportation sector per capita in the WORLD), it is disheartening that most states, including many of our largest cities, don’t even track global warming emissions.

But change is coming.

The rule follows an existing framework of performance management started in 2012 that already tracks outcomes for safety, infrastructure conditions, and reliability. This rule helps the Federal Highway Administration walk the talk and live into its sixth goal area of environmental sustainability, making use of a wide range of federal funding made available by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The rule requires:

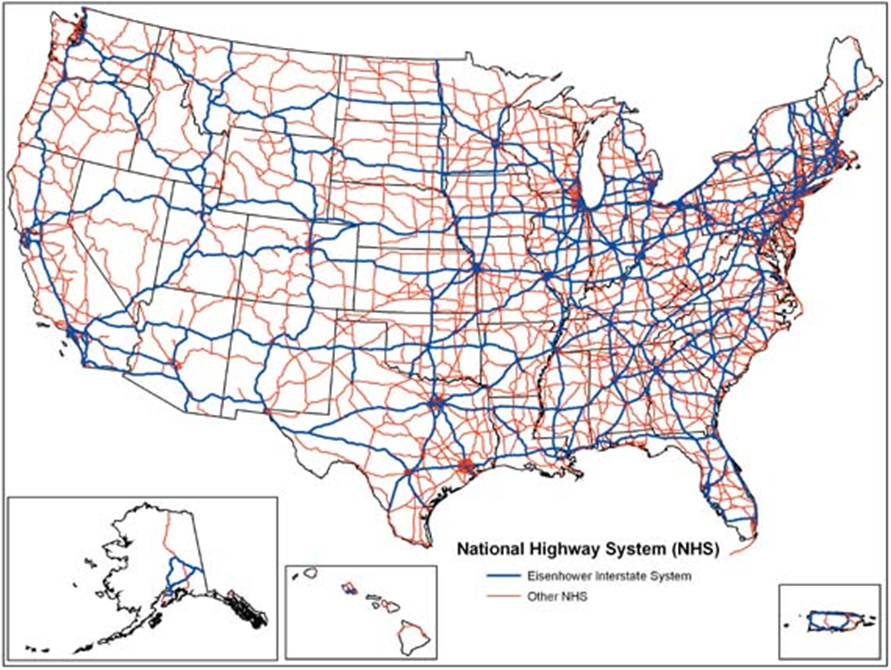

- Tracking GHG emissions: State departments of transportation and metropolitan planning organizations have many of the raw inputs for this already. They just need to put them together. Fuel sales data that is collected monthly in the FUELS/FASH system and vehicle miles traveled data that is collected from the Highway Performance Monitoring system are to be used to come up with greenhouse gas emission estimates for the 230,000 miles of the National Highway System. The US Department of Transportation specifies a recommended method for calculating this in a standardized way allowing for comparison across the country.

- Declining targets: State departments of transportation and metropolitan planning organizations are required to set carbon emission targets but figure out for themselves how they go about it. The only requirements are that they decline over time, though there are no penalties for not meeting the targets.

- Regular reporting: States are required to set 2- and 4-year targets and submit their reports and track their progress towards meeting them every 2 years, with their first reports due February 1, 2024. Metropolitan planning organizations are required to set 4-year targets, with their first targets 180 days after their State DOT establishes theirs, and to report through their existing performance measure process every 4 to 5 years.

The alphabet soup of transportation planning

This rule adds a key improvement in the process by which we plan and improve our roads, transit systems, and bike and walk-ways. However, seeing how it fits in complex, multi-billion dollar planning processes can get very confusing very quickly. A single project can take years or decades to go from an idea to implementation and can go through political twists and turns along the way. It’s no wonder that many people feel it is difficult to engage in transportation planning, even though many of us care deeply about our neighborhoods and communities and how we move around them. Let me try to untangle this process a bit.

Metropolitan planning organizations, also known as MPO’s, are responsible for approving local expenditures of federal funding, creating long-term plans through a continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative planning process, and engaging local communities in decision making processes. Each metropolitan area with over 50,000 people has one of these organizations, encompassing 83% of US residents. Wondering who your MPO is? Search up your neighborhood in this US Department of Transportation map. Areas with less people delegate these responsibilities to regional transportation planning organizations or their state department of transportation (17% of US residents).

State and local transportation authorities decide what transportation investments happen, whether it be building more highway lanes or investing in transit. In particular, every four years, metropolitan transportation organizations write a Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) which lists all transportation projects receiving federal funding. State departments of transportation put all these together into a State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP). These are “fiscally constrained” to known funding. What does that mean? Think of it like putting together a grocery list—you plan what you’ll eat in the near future and it all has to (hopefully) be within your budget. Depending on what’s available to you and how you prioritize, that can affect your health. Likewise, the choices in the TIP and STIP greatly affect the “health” of a transportation system in how it sustains safety, reliability, affordability, and equity over the long term.

Some states have already taken the lead, with results

Of the 24 states and DC that require tracking of greenhouse gas emissions, Colorado is a particularly proactive one. In December 2021, Colorado’s Department of Transportation approved a Greenhouse Gas Transportation Planning Standard that requires the state’s department of transportation and five metropolitan planning organizations to model the greenhouse gas emission impacts of the projects chosen in their long-term transportation plans (the “shopping lists” above). After adding up the emissions impacts, they must decrease by the set amounts below.

If they don’t meet this, they are required to change their mix of projects to do so, choose other measures to meet the standard (e.g. more frequent transit service, medium- and heavy-duty vehicle charging infrastructure), or risk having their funds restricted.

This has already been affecting the state in very real ways.

In 2022, the Colorado Department of Transportation announced it would halt plans for highway widenings of Colorado Route 470 in southeastern Denver and Interstate 25 through central Denver near some of the city’s low income and communities of color. This has freed up more than $100 million in funding for the state to invest in bus rapid transit and bike and pedestrian safety.

Many other areas have set declining targets for vehicle miles traveled, an important metric for how much folks are forced to travel due to car-oriented planning.

Minnesota has led with a 20% reduction target by 2050, while states like Washington and California have set similar targets. In Minnesota, the landmark 2023 transportation funding bill HF 2887 included almost $9 billion in transportation infrastructure investments, along with a stipulation that any highway expansion projects must perform an assessment of how the project conforms with the state’s greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and vehicle miles traveled reduction targets, or else it will not be allowed in the state transportation improvement program (and hence be halted).

While this federal rule does not go as far, it provides the first step of creating transparency for more informed decisions.

Next stop – a sustainable and equitable transportation future

The greenhouse gas performance measure adopted by the Federal Highway Administration rule is a key step in a people-centered vision of our transportation system. Billions of dollars of federal transportation funding are coming down the pipe as a result of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and those decisions will have a major impact on the climate. With a national rule in place, the public will now be able to see how those decisions add up, and hold state and local transportation authorities accountable to our shared responsibility to lessen the impacts of the climate crisis.

State and local transportation authorities must consider climate impacts in their decisions while also conducting deeper processes of community involvement that prioritizes those on the frontlines of pollution, displacement, and disinvestment in our transportation system. What’s needed here is for you to watch your local and state transportation planning processes to make sure they’re doing just that, joining the effort in creating more transportation options and a more mobile future for all.