Iran’s English Language outlet Press TV reports today that today (Monday) Iran has successfully launched a monkey on a suborbital flight in its new capsule called Pishgam (Pioneer). The Iranian Fars news agency said the capsule was lofted to the desired altitude of 120 km, sent back telemetry, and returned to earth where the monkey was retrieved safely.

The launch has yet to be publicly independently confirmed, but Press TV provides some images of the launcher and the monkey.

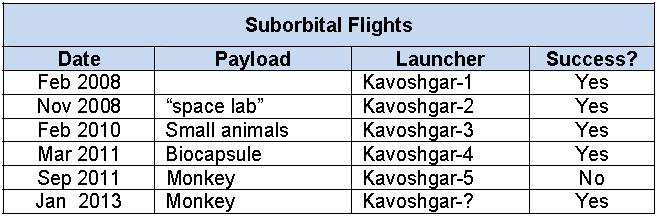

Fars reports the launch was on the Pishgam “explorer rocket,” but this is probably the wrong name. “Kavoshgar” is usually translated as “Explorer”, and all other previous suborbital launches in this effort were done with Kavoshgar rockets (see Table 1). This flight comes a bit earlier than expected, as Hamid Fazeli, director of the Iranian Space Agency, said previously the launch would take place during the ten days of festivities starting January 31 which will mark the 34th anniversary of Iran’s revolution.

The success of this flight must be gratifying. Although launches are always risky, Iran is coming off a string of failed and postponed launches. (More on that below.) The first and second launches of the Kavoshgar, in 2008, appeared successful. The third launch, in February 2010, reportedly carried a rodent, two turtles, and several worms and brought them back safely. The March 15, 2011, Kavoshgar flight carried a test bio-capsule, but no animals. Kavoshgar-5 (Explorer-5) carrying a live monkey was launched September 2011, but Agence-France Press reported that the deputy science minister said that “the launch was not publicized as all of its anticipated objectives were not accomplished.” Shortly after this, Hamid Fazeli was reported to say that Iran was indefinitely postponing its plans to send a live monkey to space. Less than a year later, though, Iran announced plans and then delayed another suborbital flight in August 2012.

Iran’s Space Technology Day

In an interview earlier this month reported by Press TV, Fazeli elaborated on Iran’s human spaceflight plans, saying that Iran would send a human on a suborbital flight within four years and into orbit in ten. (The head of Iran’s Aerospace Research Institute, Mohammad Ebrahimi, recently said that they were beginning to develop spacesuits for the human spaceflight program.) In the interview, Fazeli said that the next step in this program will be to send a capsule with a monkey (or monkeys) on a suborbital journey in a capsule called Pishgam (Pioneer).

Around the same time, Fars reported that the Iranian defense minister, Ahmad Vahidi, said that during these same upcoming festivities, Iran would unveil a new ground station, Imam Sadeq, which would be used to track space missions.

Currently Iran uses 5 ground stations, which are shown on the map below, to track its satellites.

The Chinese newspaper Xinhua reported in December that General Vahidi said that the unveiling of new achievements would come on February 2, Iran’s Space Technology Day. While the General doesn’t explicitly mention what these achievements will be, in June Vahidi discussed the upcoming completion of the new Imam Khomeini Space Center, from which satellites would be launched, the first being Tolou.

Upcoming launches

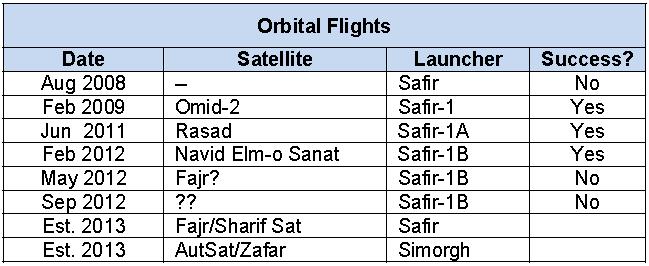

Whether the monkey’s flight will be the only attempted launch is unclear. At the end of December, Iranian Press TV reported Fazeli as saying that Iran would launch two satellites, Fajr and Sharif Sat, before the end of the Iranian calendar year—March 20, 2013. He’s also reported as saying that while they’d hoped to launch the Nahid satellite before the end of the year, more work needed to be done. However, the FARS news agency reported instead that Fazeli said that Iran would launch AUT SAT (after it had been modified) via the more powerful and yet untried Simorgh launcher, and that Sharif Sat would also be launched this (Iranian calendar) year.

A launch of the Simorgh would be a big next step. Simorgh is much larger rocket than Safir, similar to a two-stage version of North Korea’s Unha-2 launcher, with a mass of roughly 80 tons. That launcher would use a cluster of 4 Nodong engines for the first stage. It has yet to be tested.

The Kavoshgar is yet smaller than the Safir. Development of the Kavoshgar rocket itself does little to further Iran’s ability to field a long-range ballistic missile. While some concern has been expressed that Iran will improve its abilities to produce heat shielding (important both for protecting a monkey and a warhead as they return through the atmosphere), the speeds at which a biocapsule returning from a 120 km altitude and an ICBM-launched warhead travel through the atmosphere are significantly different, and the heating goes as the cube of the speed. Specifically, the speed characteristic of a suborbital trajectory such as the one the Pishgam took would be around 2 km/s; an ICBM-launched warhead will re-enter at around 7 km/s, and so a warhead would require shielding against more than 40 times greater heat load than the Pishgam.

Slightly mysterious Fajr satellite

That Fazeli said in December that Iran would launch the Fajr is notable for two reasons. First is what the Fajr can do—the Fajr satellite is meant to incrementally advance Iran’s capabilities on orbit. Its first three satellites have had very short lifetimes, being pulled out of their low orbits quickly because of atmospheric drag. Reports said Fajr is designed to maneuver after launch from an initial elliptical orbit of 300 x 450 km to a circular orbit of 450 km, at which a year and a half lifetime is a reasonable expectation, and also uses improved solar cells that will allow it to function in orbit for that long. It has been ready to go for launch, being reportedly scheduled for March 2010, then in October 2011, and again in May or June 2012.

However, no public announcement of the launch attempt ever came, and Fazeli said the launch was delayed and would happen again sometime in the next 10 months. (Fazeli again talked up the new capabilities of the Fajr satellite while in Brazil on June 23, 2012, mentioning that the February 2012 Navid satellite was the last successful launch and that the Fajr, Nahid, and Zafar satellites were still on schedule for launch.) And, as it turns out, the second reason is that the Fajr may no longer exist.

Launch failures?

It may be that the launch may have not been delayed, but that Iran did in fact attempt a launch and did not succeed. The October 1, 2012 Jane’s Intelligence Review provided an analysis of commercial satellite imagery that show a prepared launch site (without launcher) in May, and the same site with blast marks in June they say look similar to the blast marks from the Omid, Rasad, and Navid satellite launches. Jane’s concludes that the launch attempt failed. Without more information, it’s hard to tell if the Fajr was the payload and if it was destroyed.

It is curious that Iran still lists the Fajr in its roster of upcoming launches. The loss of that particular satellite may not be a setback, as Iran has fielded many satellites of similar mass from its universities and defense contractors, and should have an appropriately sized payload for any of its upcoming launches on the Safir or Simorgh. It also may have built or could build multiples of an important one like Fajr. However, the launch failure has not been widely discussed, except in specialist communities.

In fact, this may not be the only recent launch failure. Jane’s Defence Weekly reported on November 21, 2012, that a yet more catastrophic launch failure may have happened in September 2012, though again no official Iranian statement was made. Jane’s looked at DigitalGlobe satellite imagery from late September that shows final preparations being made at the Semnan launch pad for what is assumed to be a Safir launch. (Though the launcher itself is not clearly visible, this pad is too small to launch the Simorgh and the single-stage, suborbital Kavoshgar rocket is smaller and road-mobile, and would not need the umbilical tower shown.) The article provides a satellite photograph of the site taken October 25, 2012, showing a great deal of damage to the site, including to the tower.

What next?

The question, then, is what will we see in the next weeks and months? Although, reports that Iran will attempt another orbital launch before the end of March conflict in the details, the Safir’s launch pad must be repaired before any launches can take place, and in November 2012, Jane’s estimates that the new facility capable of handling a Simorgh launch is 12-18 months away.

Iran has been ambitious in its program and continues to invest resources into developing a broad space program. The next couple of months will hopefully provide some insight on what Iran’s priorities and progress.