When I look back at 2023 and consider UCS’s advocacy around the federal Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), I feel like it was a year of tears. Happy tears, sad tears, angry tears, tears of disappointment, and tears of grief. In politics you’re not supposed to cry, but it’s not possible to work and build relationships with people who have been diagnosed with cancer, who have lost children or entire families, and leave the emotions out.

RECA is a federal program that provides cancer screenings and small one-time payments to some uranium miners, atomic veterans, and communities near the Nevada Test Site, where the US military conducted 100 above-ground tests between 1951 and 1962. Beginning with the Manhattan Project and throughout the Cold War, these US nuclear activities poisoned people—they breathed in radiation in mines, drank contaminated milk from local farms, flew military planes through mushroom clouds, saw their cows turn ghostly white and buried lambs born with two heads. And the whole time the government told them they were safe.

As evidence that people had been poisoned mounted, RECA was enacted in 1990. It included an apology “on behalf of the nation” to miners and downwinders “who were involuntarily subjected to increased risk of injury and disease to serve the national security interests of the United States.” Over the years there were successful efforts to update and improve RECA by including communities originally left out and removing barriers for Indigenous claimants. But the last time that happened was in 2000.

Over the next 23 years, more communities would discover that they, too, had been exposed to radiation from testing, mining, and nuclear waste. They would fight tooth and nail with their government to see this same kind of recognition: uranium miners employed after 1971, downwinders of the Trinity Test in New Mexico, veterans who cleaned up nuclear waste, downwinders beyond the handful of counties originally designated as “exposed,” communities near nuclear waste and production sites. But in all those years, Congress has ignored their pleas.

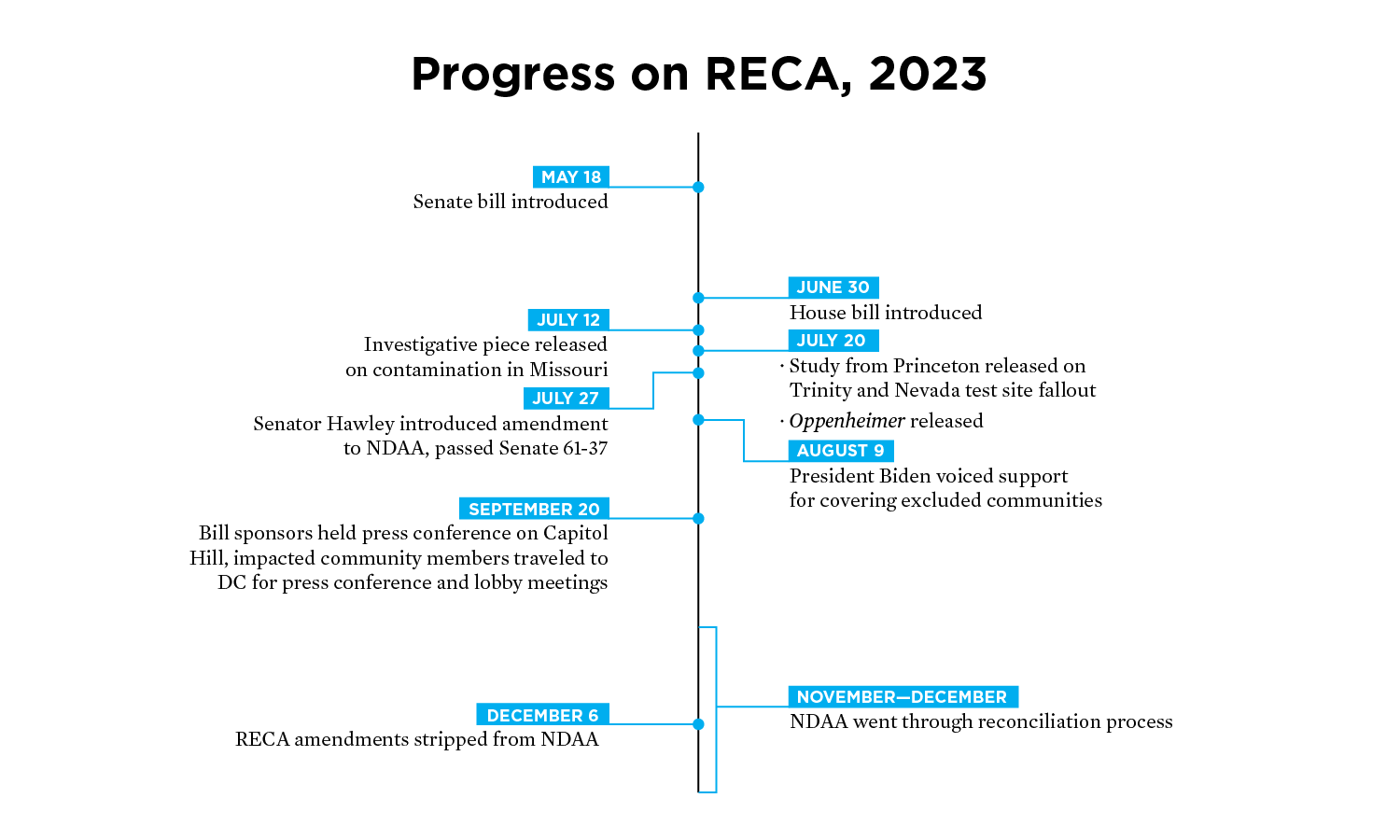

In so many ways, 2023 was a year of incredible progress—of happy tears. This year was the closest communities have come in decades to finally receiving the recognition and justice they deserve, and the support they so desperately need. After bills to strengthen RECA were introduced in the early summer of 2023, there was a flurry of activity: an investigative piece in Missouri detailed decades of nuclear contamination in St. Louis, a new study came out from Princeton that showed that fallout from nuclear tests spread across the continental US, farther than we ever realized. Oppenheimer was released, bringing unprecedented attention in the media and public of these issues while completely leaving out the communities harmed by Oppenheimer’s atomic bomb. And in late July, the Senate passed an amendment 61-37 to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), an annual military budget bill, that would support these communities.

Hearing of the Senate vote, Paul Pino, a Trinity test downwinder, said, “I’m stunned. I’m shocked in the most wonderful way…The world is bright and beautiful and full of hope. It renews my faith in the leaders of this country. Republicans and Democrats working together, I can’t believe that.”

This vote bolstered so many across the country who had been fighting for decades. We even heard President Biden voice his support for covering excluded communities. Affected communities followed this up in September with a flood of meetings in DC and an inspirational and moving press conference, hosted by RECA champions in the House and Senate. Speakers expressed a fervent wish, maybe even a belief, that Congress would finally do what is right, could put partisanship aside, could put people first, and protect and strengthen RECA before the end of the year.

During this time, I saw community members give it their all: they traveled to DC to meet with Congress, gave media interviews, shared their stories wherever they could, organized their communities, and supported each other to keep fighting. We watched, heard, and read more than 130 news stories on RECA in the second half of 2023 alone.

Support for this cause came from both side of the aisle: Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri led the NDAA amendment and became an outspoken and passionate leader on the issue; Representatives Paul Gosar and Eli Crane of Arizona, of the House Freedom Caucus, rallied behind this, with Representative Gosar even writing that Congress should put the cost of this aside to do what is right. And at the same time, we saw members on the other side of the political spectrum standing with them, like Representative Cori Bush of Missouri and Representative Leger Fernandez of New Mexico.

But then came the tears of disappointment—the angry tears. We may never know exactly what went down behind closed doors, but it seems that ultimately, the decision on whether to protect and strengthen RECA sat with Speaker Mike Johnson and Leader Mitch McConnell. In December we learned that they chose to strip RECA out of the defense budget bill.

Tina Cordova, another Trinity Test Downwinder, didn’t pull any punches in a press release after learning about the decision. She said, “Certain members of Congress care nothing about the people who’ve been dying for 78 years without assistance. They see nothing wrong with looking away from our basic human right to appropriate health care. While our defense budget continues to grow unabashedly we are left to hold bake sales, garage sales, and sell livestock to meet our growing health care expenses when we are sick and dying. Shame on them for taking this position.”

People in every exposed community I’ve worked with tell me it seems like the US government is just waiting for people to die so that this problem goes away. And in many ways, the decision to strip RECA from the defense budget bill felt like confirmation. Many of these advocates have already been waiting for nearly 80 years. How much longer can they wait? How many more people need to die before the government addresses their pain?

This is why this year was also filled with tears of grief—why every year that Congress fails to take action is filled with grief.

Maggie Billiman, originally from the Sawmill Chapter of the Navajo Nation, said to me around this time, “My sister was just diagnosed with bladder cancer. My uncle passed away a few weeks ago from kidney cancer. Years ago my father died from stomach cancer. All diseases covered under RECA, but it was too late for my uncle, my father, and so many others in my family. As my father was dying, he asked me to research cancer care, to try and help him, because it was so hard to get care. I couldn’t deliver that to my father, I couldn’t save him. But I want to try and deliver that help to my family, to my people, to the Navajo Nation. That’s what I’m fighting for.”

But through their tears, these community members refuse to give up—they are resilient, and they will not stop fighting for what is right.

RECA will expire in June 2024, following a two-year extension passed by Congress in 2022. We know there will be a temptation for lawmakers to yet again kick the can down the road and do another short-term extension, once again leaving behind too many people. That’s simply not an option this year. Too many people are sick and need help, too many people have already died.

We will keep fighting to protect and strengthen RECA. Our first opportunity seems to be attaching the RECA amendments to budget bills that now expire on March 1 and March 8. But we will look for any and all legislative options, including holding hearings, introducing a stand-alone bill, or finding other vehicles to attach this legislation to. UCS is ready to stand and fight with these communities.

As advocates I’ve worked with pass away, or tell me of their friends and family who have passed away, I feel more and more that I’m doing this work in honor of those who have died. But we’re also fighting for the living. In 2024, I want to see those still with us in Washington DC, not for yet another lobby meeting, but to stand next to the president as a strengthened RECA is signed into law.