The year 2023 was by far the warmest in Earth’s recorded history, and perhaps in the past 100,000 years, shattering the previous record set in 2016 by 0.27°C (0.49°F). According to recent data from NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Information, 2024 is likely to be even warmer than 2023.

Scientists are sounding the alarm because this warming is shockingly big—bigger than what we would have expected given the long-term warming trend from fossil fuel-caused climate change. But why were 2023 and 2024 so warm?

The reason why 2016 was so warm was because of a strong El Niño event—a naturally-occurring cycle in the Earth’s climate system—which typically leads to a spike in Earth’s global-mean temperature. In that year, El Niño added to the increased warming caused by the build-up of heat-trapping emissions in the atmosphere, leading to that record-breaking heat.

This is why 2023 and 2024 are so alarming: El Niño was only moderately strong (contributing a small amount of warming) in 2023 and was in a neutral state for most of 2024 (contributing almost no warming), so we cannot attribute the record-breaking warmth of 2023 and 2024 to El Niño like we did in 2016, and we definitely should not be shattering heat records under a neutral state El Niño. In other words, 2023 and 2024 have been much hotter than scientists’ predictions.

What could be a potential explanation for the record-breaking warmth? This question was a focus at the 2024 annual American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in Washington, D.C., where 30,000-plus scientists gathered to present their latest research. The two leading theories to explain the record-breaking warmth are a reduction in tiny particles in the atmosphere called aerosols due to shipping fuel regulations that reduced sulfur oxide (SOx) emissions, or decreasing cloud cover. Before we get to those two likely culprits, let’s talk about albedo.

What is albedo?

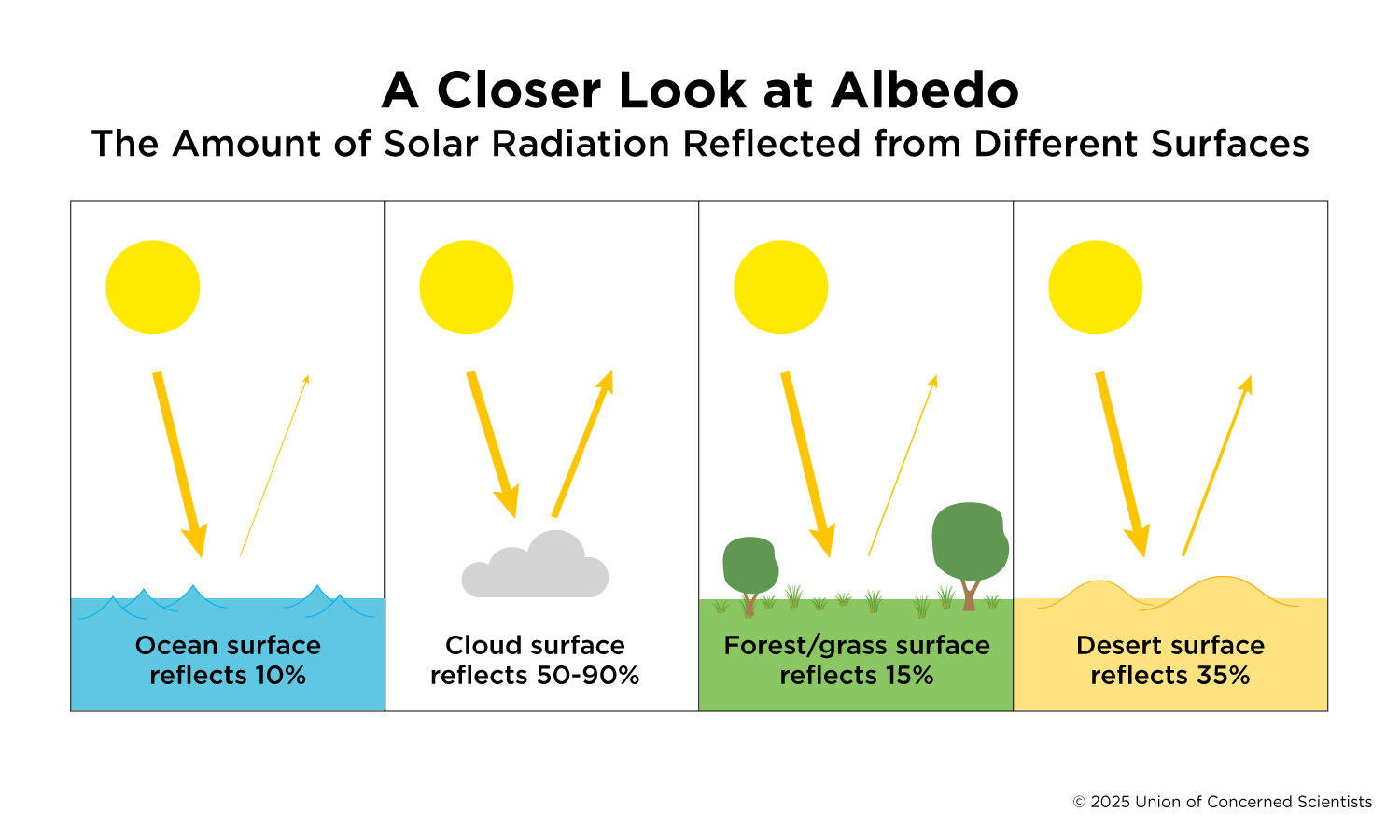

A concept that’s important in both of these theories is planetary albedo. Albedo is the total reflection of incoming solar radiation by Earth. This reflection is done partially by lighter-colored surfaces such as ice sheets and ice shelves, clouds, deserts, and also by aerosols. Think of walking outside on a sunny day after a snowstorm or in a desert; the sun’s rays are reflected by the light surface, making it harder to see. These solar rays are normally reflected out to space.

The planet typically reflects about 30% of incoming solar radiation, but this number can change slightly depending on how much snow- or ice-cover there is, on the amount of cloud cover, or on how many aerosols are in the atmosphere (remember, these are tiny atmospheric particles that reflect light). Humans have a direct effect on albedo through emitting industrial aerosols such as sulfates, which accumulate in the atmosphere due to the burning of fossil fuels.

You might be thinking, “if the burning of fossil fuels increases Earth’s albedo due to additional aerosols in the atmosphere, shouldn’t this offset any impact from the effects of increased heat-trapping emissions like carbon dioxide?” It’s a great question, but the warming effect from heat-trapping gases far outweighs the cooling effect from industrial aerosols.

Reduction in aerosols leads to albedo decrease

A popular theory that could explain why the past two years have been so warm has to do with a change in aerosol emissions due to new shipping fuel regulations aimed at helping to address pollution that harms health and the environment. In 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) reduced the limit on the amount of sulfur in ships’ fuel oil, which then led to a reduction in sulphur dioxide and particulate matter emissions which form aerosols in the atmosphere.

According to two recent studies, this reduction in aerosols may have led to a spike in the global-mean temperature. How? As industrial aerosols decreased due to this new regulation, particularly over the North Atlantic Ocean, the planetary albedo slightly decreased, which means that more incoming solar radiation was absorbed by the planet rather than reflected.

However, another study found that the effect of additional industrial aerosols in the atmosphere would only affect global-mean temperature by a couple hundredths of a degree, rather than the 0.27°C observed in 2023.

Of course, continuing to strengthen public health-based standards to cut harmful air pollution from burning fossil fuels, including sulphur dioxide and particulate matter, is essential and lifesaving. Further scientific work is underway to help advance our understanding of how and how much this contributes to changes in industrial aerosols and how that may be influencing the rate of warming. Meanwhile, sharply cutting our use of fossil fuels is the best way to limit carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, the primary driver of climate change.

Diminishing cloud cover due to warming creates more warming

A study released just last month, and another preprint of a study presented at AGU, provide a different explanation for the spike in global-mean temperature: clouds. In this case, the authors of both papers argue that a decrease in cloud cover led to the decrease in planetary albedo.

Over the last few decades, there has been an observed decrease in total planetary cloud cover, especially over the North Atlantic Ocean off the Northeast US coast. Here, low-level cloud cover has decreased drastically, mostly related to an increase in ocean surface temperature.

The decrease in low-level cloud cover due to warming ocean surfaces is particularly alarming because the process could be the manifestation of a feedback associated with global warming: as the oceans warm, low-level cloud cover decreases, which results in a lower planetary albedo and thus a faster warming world.

Ocean surface temperatures in the North Atlantic could also be warming so much due to a weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which I blogged about in November. While ocean surface temperatures are increasing globally due to fossil fuel-caused climate change, they are warming even faster off the US Northeast coast, which could be the result of the AMOC slowing down and pooling warm water in the region.

Important questions are still being sorted out

Climate scientists are still trying to figure out what exactly made 2023 and 2024 so warm. We discussed some potential reasons that could explain the spike in warming, but the details haven’t been ironed out quite yet.

What’s interesting is that the sudden warming could also be due to a combination of the two theories.

Did you know that in order for water droplets to form in the atmosphere to create clouds, they need a tiny particle to condense onto? These tiny particles are called cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), and one type of CCN is industrial aerosols such as sulfates. After the IMO lowered sulfur in shipping fuel oil, less sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere could have resulted in less CCN available for cloud droplets to form, resulting in a lower planetary albedo.

To perhaps add another layer to everything, during my PhD research, I studied how different patterns of ocean surface temperature affect the rate of global warming. For example, if the West Pacific warms more than the rest of the world, then the planet will actually warm at a slower rate than if that warming was distributed evenly across the ocean’s surface.

We found that the most likely ocean surface pattern of warming in the near future, which is currently developing, will result in a rapidly warming planet. This could very well be a piece of the puzzle as to why 2023 and 2024 were so warm.

Scientists continue to sound the alarm

The additional warming in 2023 and 2024 adds a layer of complexity to fossil fuel-caused climate change (and not the kind of complexity we want, given that the planet seems to be warming more rapidly than before). These two ideas from the science community are still being ironed out, and it will take some more time to understand exactly what caused this spike in global-mean temperature.

One thing is for sure though: the planet is warming mainly due to increased heat-trapping emissions in Earth’s atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels. The only way to slow down warming is by reducing said emissions through a fast and fair transition to clean, renewable energy.