Record-breaking rain and snow across much of the West late last year came as welcome relief to many, including farmers and communities in California’s Central Valley, but that relief was short-lived. The dry months that have followed have only increased the potential for another year of drought and severe water shortages for many farms and households, with disadvantaged communities likely to suffer the most. This news is particularly difficult on the heels of a new report finding that the 2021 drought alone cost $1.7 billion and over 14,000 jobs. The situation is disheartening but also foreseeable, as the most recent IPCC report has harshly reminded us that climate change is here and the risks are growing. And it will only get worse if governments fail to act.

As part of our series on climate change in California’s Central Valley, I’ll focus here on the state of agriculture in the region and ways in which current farming practices are vulnerable to and exacerbate drought conditions, climate change impacts, and other social and environmental concerns.

Farming is big business in the Central Valley—and that’s part of the problem

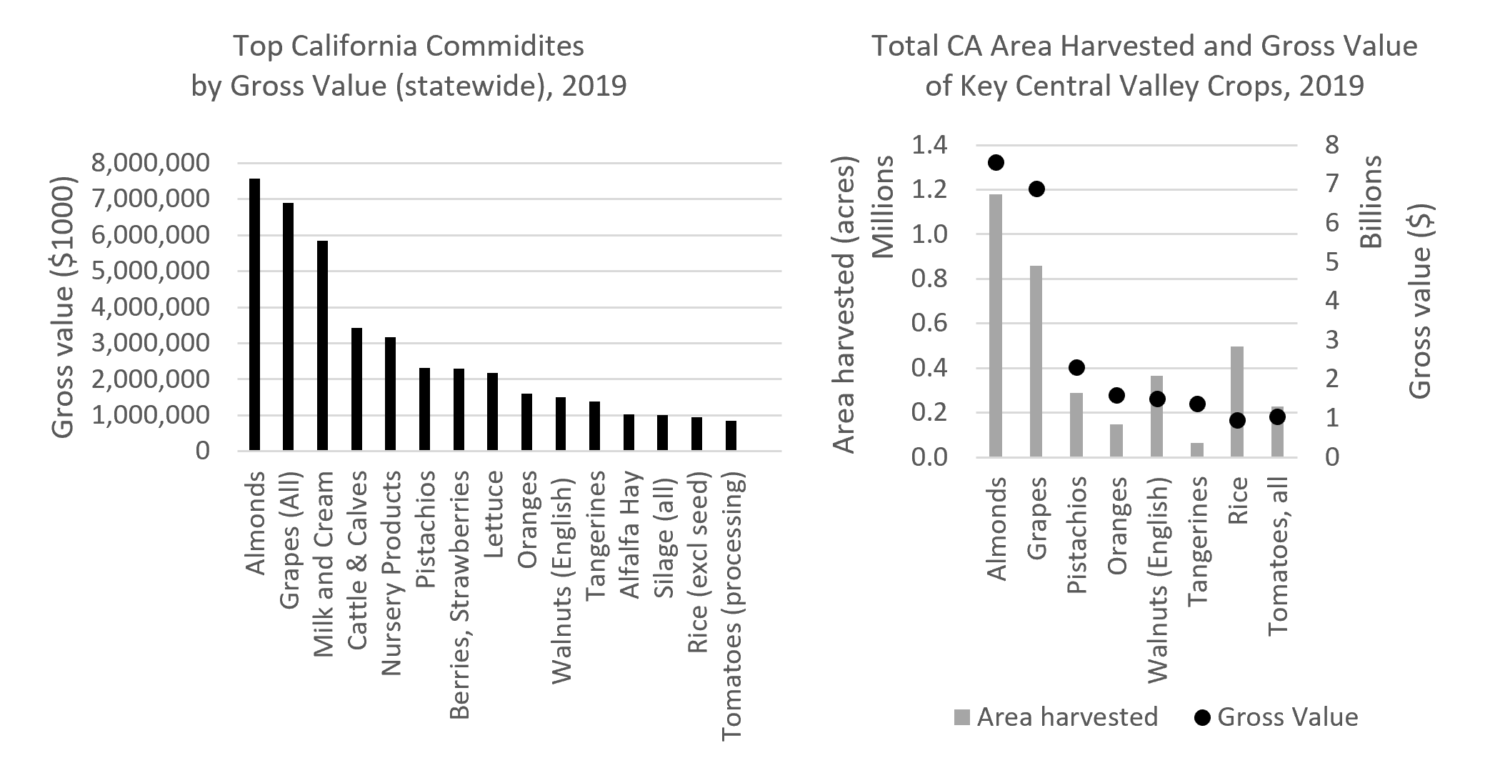

Farming and food production in California and its Central Valley are extremely vulnerable to drought fueled by climate change, and the industry’s sheer size—in terms of water demand but also money and associated political power—is a big reason for that. Overall, the state of California produces over 400 commodities worth over $49 billion in sales. The Central Valley alone produces over 250 crops with a value of about $17 billion per year, contributing an estimated 25 percent of the nation’s food.

The Central Valley includes parts of 19 counties, which together are home to more than 35,000 farms and nearly 6 million harvested acres. These counties also include 8 of the top 10 agricultural counties in the state: Fresno, Kern, Tulare, Stanislaus, Merced, San Joaquin, Kings, and Madera. Of the top 15 commodities in the state, by total sales, Central Valley counties are the leader in 11 of them. The top commodities across Central Valley counties include almonds, pistachios, table grapes, milk, oranges, wine grapes, walnuts, cotton, livestock (cattle & calves, chickens), and nursery crops (fruit, wine, and nuts). Other major Central Valley crops include cereal grains (such as corn), hay, tomatoes, vegetables, and other citrus and tree fruits.

This may sound impressive, but there are also significant downsides to achieving these levels of production.

In general, trends toward increased industrial farming and consolidation create and amplify numerous risks for farmers, workers, communities, and eaters. For example, farms that rely on large amounts of water and degrade soils often contribute to climate change and use large amounts of fertilizer and toxic pesticides, affecting lives and livelihoods. And risks can grow in response to a number of factors, such as when workers are directed to apply high levels of toxic pesticides in increasingly extreme heat.

In the Central Valley, one particular concern is that the industry demands vast quantities of water, even as that resource is increasingly scarce. And that is leaving many farmers, workers, and communities highly vulnerable.

The immense and growing water needs of Central Valley agriculture

Central Valley agriculture’s high water demand is due to several factors, including the sheer number of acres being farmed, the many crops that are grown using high amounts of water, the dominant farming practices, and the hot and dry climate. To offer some perspective, while the Central Valley has less than 1 percent of the nation’s farmland, it has 17 percent of the nation’s (and 75 percent of California’s) irrigated land. Furthermore, a significant portion of the water supply used for this irrigation comes from local groundwater resources, and the region accounts for a staggering 20 percent of the entire nation’s groundwater demand.

This enormous water demand places a strain on available water resources—and contributes to unsustainable and dangerous levels of groundwater depletion. Without action to reduce it, agricultural water demand is likely to increase. Increased demand is expected in part due to the higher evapotranspiration rates driven by higher temperatures brought about by climate change (within the Central Valley, across the Southwest, and elsewhere). But decisions on what to grow and how to grow it are also influencing water demands, and are already compounding climate change impacts in dangerous ways.

How farmers, workers, and communities in the Central Valley suffer from drought

During drought, when precipitation is reduced and surface water supplies are likely to be more limited, Central Valley farmers have two basic options to work with: finding more water and using less water. Both involve difficult decisions and can lead to a variety of short- and long-term consequences.

In many cases, California farmers who have found more water during drought have done so by drilling deeper wells, but this is pricey and out of reach for many farmers. And where farmers have the resources to drill deeper, this can leave neighboring farms and communities—particularly low-income communities and communities of color—without clean water (or without any water: an estimated 12,000 people in the Central Valley ran out of water during the 2011-2017 drought, and thousands ran out of water just last year). Continued groundwater depletion would make this option for farmers even more limited, costly, and harmful to others. The state’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act should also be curbing current levels of groundwater depletion, eventually, but progress has been slow.

Using less water, then, would be better on many fronts, but is no less complicated. During the 2014, 2015 and 2016 drought in California, Central Valley losses included tens of thousands of jobs and billions in output. As noted earlier, new estimates indicate that the 2021 drought led to statewide costs of $1.7 billion and over 14 thousand jobs; many of the costs were felt hardest in the Central Valley, where approximately 385,000 previously planted acres were left bare. Looking to the future, one study suggests that reductions in groundwater and surface water in the San Joaquin Valley could require leaving over 500,000 acres of farmland unplanted, with additional implications for farmers, workers, and the state’s economy.

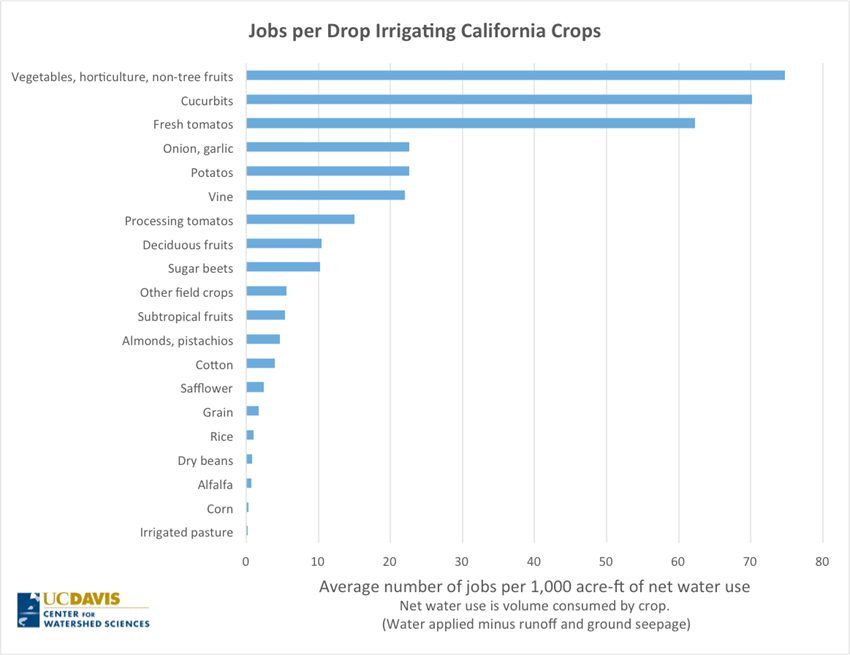

Furthermore, for farmers who use less water, one complicating factor in determining their best options is that some water-intensive crops tend to be very profitable, causing severe water shortages to play out in unexpected ways. For example, almonds and pistachios are some of the thirstiest crops. However, during the 2021 drought almond production was only reduced by about 10 percent while pistachio production reached new highs, and lower global supply for both raised prices enough to amount to a good year, economically. But crops like almonds and pistachios are long-term investments that commit farmers to decades of water demands and support a low-number of jobs per drop of water relative to other major crops.

Today’s farms are particularly vulnerable to drought’s cascading consequences

To make matters worse, water shortages will likely amplify other challenges created by climate change and dominant farming practices, all of which can have significant ripple effects.

For instance, one study found that the California farmland suitable for warm season crops like tomatoes, cantaloupe and carrots may shrink considerably by 2045 due to increased temperatures. Other estimates suggest that over half the Central Valley may not get cool enough for long enough to grow peaches by mid-century, and pistachios and walnuts may not be able to grow in California by as early as 2060. And when rain does come, extreme rain events like those seen in California in October and again in December 2021 will continue to erode and degrade vulnerable soils, leaving farms even more prone to future drought and floods.

Considering all of the issues, there are clear risks for food supplies. However, given the highly globalized food system, most consumers haven’t yet seen the effects reflected in their grocery bills. For example, the 2014-2015 California drought, had limited impacts on food prices.

But that could change. Over the course of 2021, coffee, sugar, and wheat prices all increased in response to extreme weather that devastated crops in major production areas stretching from the United States to Brazil.

We need a more sustainable, resilient, and equitable agriculture—in the Central Valley and everywhere

Farmers, workers, and communities are already suffering from increasing drought, climate change, and other persistent challenges, and change is overdue. Proactive and intentional actions will improve the chances of identifying ways forward that are equitable and just, particularly for those whose lives and livelihoods will be impacted by change.

Fortunately, there are farming practices, policies, and programs that could help move things in the right direction. Shifts in practices could include things like growing more drought-tolerant crops, boosting soil health, practicing dry farming, utilizing practices that require fewer pesticides and fertilizers, and repurposing land for some uses that require less water (such as solar arrays or wildlife habitat). In terms of policies, we can continue to support and strengthen important initiatives like California’s Healthy Soils Program and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. At the federal level, we can push for much needed provisions to support farmers, protect farmworkers, halt consolidation, advance research, and increase adoption of more sustainable farming practices. In 2021, policymakers took encouraging steps on the climate and agriculture front, and bills like the Agricultural Resilience Act and the Justice for Black Farmers Act could help promote even more progress, especially as Congress prepares to write a 2023 farm bill.

While there are opportunities ahead, there is also long way to go. For the sake of Central Valley farmers, workers, and communities, and all of us who depend on them, it’s time for more action.