For decades, California has been a world leader in the fight against climate change. The state has taken bold steps to decarbonize its economy, driven by California’s aspirational goals. These goals include reducing greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030 and transitioning to 100 percent zero-carbon electricity by 2045.

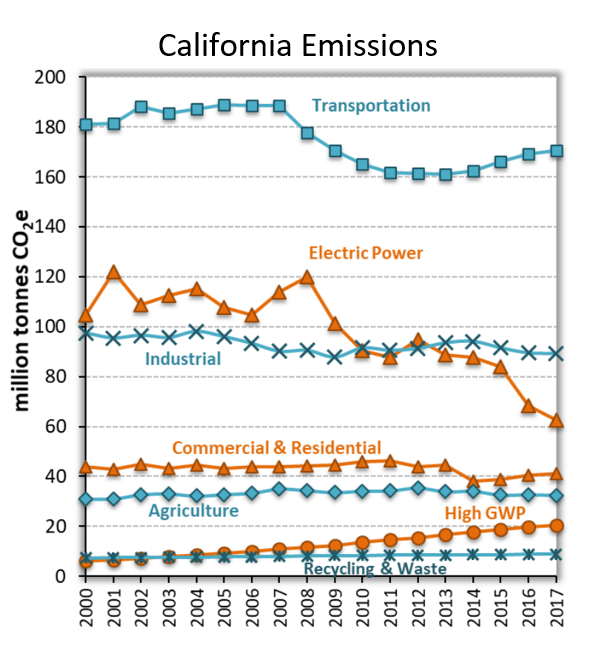

But as the years pass by and California’s climate change goals become increasingly ambitious, the pathway to achieve the state’s goals is becoming more challenging. California’s electric sector has, historically, been the shining star of decarbonization, having slashed its emissions in half in only a decade (see figure below). But now that the state needs its electric sector to ratchet down emissions faster than ever before, California’s electric sector is poised to let us all down.

Over the past two decades, California’s electric sector has drastically reduced its global warming emissions while other sectors of the economy have made little progress. In the decade to come, California needs to start reducing emissions in other sectors of the economy while continuing to ratchet down electric sector emissions.

A shining star grows dim

The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) plans the future of the state’s electric sector via the Integrated Resource Planning process. The CPUC recently released their proposed plan for the coming decade.

To be blunt, the plan is a disappointment.

The plan acknowledges that California’s electric sector must continue to decarbonize, but the question at hand is: how drastically should the electric sector reduce its emissions over the next decade? The California Air Resources Board (CARB) recommends electric sector global-warming emissions be reduced to 30-53 million metric tons (MMT) by 2030.

If you’re thinking, “that’s a pretty big range,” then I agree! California’s global-warming emissions from the electric sector currently hover just above 60 MMT. The upper end of the CARB range represents a modest reduction in emissions, while the lower end of the range represents roughly a halving of emissions! (The range is so large because there’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding the extent to which we can reduce emissions in other sectors of the economy – I’ll return to this topic later in this post.)

The CPUC’s plan calls for reducing electric sector global warming emissions only to 46 MMT by 2030. However, due to modeling issues, the CPUC’s plan actually corresponds to approximately 51 MMT, perhaps even higher, pushing it up to the very top of the CARB range.

The CPUC’s insufficient proposal comes despite their own long-term analysis that indicates the state’s electric sector should reduce its emissions to 30 MMT by 2030 (as shown in the figure below), the low end of the CARB range.

So what’s the right number? And why is the CPUC dragging their feet?

The CPUC conducted analysis looking ahead to 2045 to understand if the state’s electric sector is on track to meet its near-term (2030) goals and long-term (2045) goals. All three long-term scenarios (high hydrogen, high electrification, and high biofuels) involve much deeper reductions in emissions by 2030 than the 46 MMT scenario (represented by the top gray line) that the CPUC is planning to pursue.

California’s electric sector should reduce its emissions to 30 MMT by 2030.

Here are three reasons why the target should be more ambitious.

Reason 1: Time is not on our side

Decarbonization takes time. Renewable power plants don’t just appear overnight—they take years of planning, negotiation, financing, permitting, and construction. In order to integrate those renewables onto the grid, California will also need new transmission lines, which take years of planning, permitting, and construction as well. To reduce global warming emissions, California’s electric sector needs as much time as we can give them to plan the required investments.

That’s why we should lower the electric sector’s emissions reduction target now. If we wait too long, it may be too late.

While planning for a lower electric sector emissions target, California’s electricity providers may become more interested in developing technologies like offshore wind.

California’s electricity providers will need to make many new investments over the coming decade, and they plan those investments based on the emissions reduction target. If we were to lower the emissions reduction target halfway through this decade, then there may not be enough time for electricity providers to make the most cost-effective investments. For example, many electricity providers are currently investing heavily in solar and battery storage. However, to cut emissions further, electricity providers may become more interested in other technologies, such as geothermal or offshore wind. Those technologies will inevitably take many years to build, and if we don’t give electricity providers enough time to plan for a lower emissions target, they may not be able to make those investments and reach the target.

In addition, California’s electric sector is currently undergoing a transition, with more and more Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs) providing electricity to the people of California. In the past decade, 19 CCAs have formed in California, and they now serve more than 10 million customers. Many of these CCAs are very new, and they will be responsible for making many of the clean energy investments needed to decarbonize the electric sector. There has been concern over the state’s ability to achieve its decarbonization goals while relying on brand new CCAs to do much of the work, but regardless of whether you think those concerns have merit, we can all agree that allowing more time would help. To give CCAs a fair chance at leading California’s decarbonization efforts, we should lower the target to 30 MMT now so that CCAs can begin planning as soon as possible.

In short, if we wait too long to lower the electric sector emissions target, electricity providers might not be able to procure the most cost-effective resources, and newly-launched CCAs may struggle to meet the shifting requirements.

Reason 2: Better early than late

The reason CARB gave such a wide range (30-53 MMT) for 2030 electric sector emissions is because no one knows with certainty the extent to which other sectors of California’s economy will reduce their emissions. If, for example, California’s transportation sector switches to zero-emission vehicles much faster than our current projections, that would take the pressure off California’s electric sector to decarbonize so quickly.

In the next decade, we need other sectors of California’s economy, such as transportation and commercial/residential buildings, to drastically reduce their emissions. But to ensure California achieves its 2030 goals on time, we shouldn’t count entirely on other (less controllable) sectors of the economy to reduce emissions. We know exactly what California must do to reduce electric sector emissions further, but reducing emissions in other sectors of the economy is still a work in progress. To ensure California achieves its 2030 climate goals, the state’s electric sector should plan to decarbonize even further – all the way down to the point where it emits only 30 MMT in 2030.

Other sectors of California’s economy, such as the transportation sector, will need to make significant emissions reductions by 2030, but we shouldn’t count entirely on those other sectors to ensure the state achieves its climate goals.

What happens if other sectors of California’s economy exceed our decarbonization expectations while the electric sector reduces its emissions to 30 MMT? In that case, California may achieve its 2030 climate goals early. It wouldn’t be the first time that California has achieved its goals early and demonstrated that it’s possible to decarbonize while continuing to grow the fifth largest economy in the world.

California’s electric sector will need to make many new investments to reach 100 percent clean electricity by 2045, so investing now to achieve the 30 MMT emissions target by 2030 would not be a waste – instead, it would be a down payment on the 100 percent clean electricity goal. We will need to make all these investments sooner or later, it’s just a matter of when.

As we face the existential threat of climate change and its horrific impacts, it’d be much better for California to continue its aggressive and successful emissions reductions while retaining its status as a leader in the fight against climate change. Now is not the time for complacency or short-sightedness. Now is the time to do everything we can to ensure we achieve our climate goals.

Reason 3: The cost is within reason

It’s no secret that it costs money to build renewable power plants. But the cost of renewable energy has plummeted over the past decade, making investments in clean energy much more affordable.

So how much would it cost to ratchet down electric sector emissions to 30 MMT?

In comparison to an electric sector emitting at the higher 46 MMT level, CPUC analysis indicates it would cost an additional $1.2 billion per year to lower emissions to 30 MMT. That sure sounds like a lot of money, but let’s put that number in perspective.

- California’s three investor-owned utilities recently proposed spending more than $10 billion over the next three years to reduce the risk of sparking wildfires.

- California’s three investor-owned utilities collect roughly $30 billion per year to pay all the costs associated with providing electricity to their customers. Of that total, $13 billion goes towards electricity generation.

- Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon and one of the richest people in the world, has a net worth over $100 billion. (Maybe California could get part of his $10 billion pledge to fight climate change to pay for the additional renewables?)

Don’t get me wrong, an extra $1.2 billion per year is a lot of money. But in comparison to other utility expenditures (and the costs of climate change impacts!), it’s certainly within the realm of reason.

We should still keep a close eye on costs

All that being said, we do need to be mindful of the cumulative impacts on electric rates. California’s utilities are currently spending vast sums of money on wildfire mitigation, and that spending will inevitably drive up rates. That spending, in combination with this extra spending on renewables, could push electric rates over the top. If we reach the point where electricity is so expensive that vehicle and building electrification no longer offer savings (which they currently do in many cases), then the grand plan to “electrify everything” in order to decarbonize the economy may face insurmountable economic obstacles.

Electric rate design is a whole other can of worms that I won’t get into here. We should do what we can to keep electric rates low to encourage electrification (and decarbonization) of other sectors of the economy. But I’m not convinced that we need to hold off on decarbonizing the electric sector in the hopes that it will spur decarbonization in other sectors. Delaying decarbonization risks other costly and dangerous consequences for public health, our prosperity, and the environment. We need to do it all, and we need to do it now.

What next?

The California Public Utilities Commission has issued its proposed plan for California’s electric sector, but they have not made a final decision yet. There is still time for the CPUC to change course and chart a path towards much lower levels of electric sector global warming emissions in 2030.

UCS is working hard to ensure that the CPUC and California’s electric sector don’t let us down when we need their incredible powers of decarbonization most.