Remember the promises to reduce carbon dioxide emissions that were made in Copenhagen in 2009? Since then, there has been a growing gap between what nations collectively need to do to meet their stated goals and what they have actually put on the table in terms of commitments out to 2020. Yesterday that changed – at least in the United States.

In an important step on climate action, President Obama put forward a plan that would allow him to keep his Copenhagen commitment to reduce U.S. carbon dioxide emissions to 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020. (Read further UCS analysis of the speech here.)

This post is part of a series on President Obama’s Climate Action Plan.

This post is part of a series on President Obama’s Climate Action Plan.

But is that enough? From a scientific perspective, it can be hard to say. When we look at the global amount of carbon dioxide going into the atmosphere, there are a lot of ways countries could collectively take action to bring global emissions down to zero in the long term. Ultimately, that’s what we’ll need, otherwise carbon dioxide will continue to accumulate and change our planet essentially forever. This year saw us pass 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere for the first time in human history. For many scientists, it was a sobering milestone.

“Tapping” the brakes on climate

The president compared his plan to “tapping the brakes” on a car before coming to a complete stop. That’s a good way of thinking about it and in the context of our global carbon goals, it’s an accurate way to characterize the limits of what the president can accomplish on his own under existing law. Obama’s speech is an indication that this Administration is willing to press a little harder on the brakes than it has in the past. When a new driver comes into the Oval Office, he or she will have to do more to complete the braking, too. But if we don’t do more in the short-term to reduce our emissions we’ll be left with a stark choice: slam on the brakes in ways that could harm our energy security or lock in much higher levels of warming.

The president also used this event as an opportunity to educate the U.S. public on the importance of this inter-generational issue, to highlight the severity of the impacts we are already seeing domestically, and to emphasize the need for the U.S. to return to the international arena to encourage action on climate. However, this historic commitment has to be just the beginning of the aggressive emissions reductions we need to achieve globally in all sectors. As the president noted, “science, accumulated and reviewed over decades, tells us that our planet is changing in ways that will have profound impacts on all of humankind”.

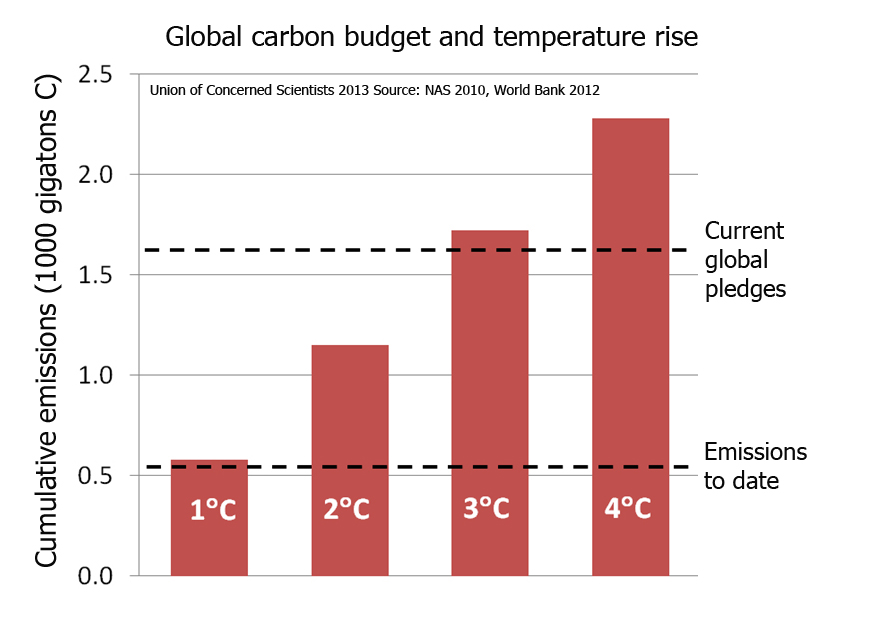

The global carbon budget and the 2°C limit

Carbon emissions are currently increasing globally by about 3 percent per year, and show little sign of slowing. The global recession was nothing more than a minor speed bump to these increases. In a similar way to considering a personal spending budget, the cumulative amount of carbon emitted over time represents our carbon budget. Some estimates suggest globally we have an allowance of roughly 1000 gigatons of carbon from the year 2000 to mid-century if we are to have a 75 percent chance of staying below a 2°C (3.6°F) warming threshold. International negotiators have recognized 2°C above the pre-industrial global average temperature as a level of warming we should stay below to avoid “dangerous” interference with the climate system.

- Estimates from a National Academies of Science report in 2010 and a World Bank report in 2012 show that the pledges from Copenhagen will likely lead to a 3°C warming.

World Bank: Copenhagen pledges head for 3°C and beyond

A report last year by the World Bank made it clear that emission reductions need to be swift and deep. Their analysis showed that, even if the pledges made at Copenhagen were all met, the world is still likely on a pathway to well over a 3°C warming. In addition a report from the National Academies of Sciences in 2010 shows we have already committed to a 1°C warming from current emissions.

So – can the U.S. pledge of a reduction in emissions of 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 get us to where we want to go? Not on its own. But it is a powerful message that this country is finally taking the issue seriously and returning to the international negotiations with as much good will as possible in light of the hamstrung U.S. political climate.

Earth’s global average temperature has already risen by 0.8°C since the late 1800s, so we have a little over a degree of wiggle room. However, at current rates of emissions, Earth’s 2°C carbon budget will be entirely spent by the middle of the 2020s, about a decade from now. Without stronger actions, scientists are telling policy makers that we will blow past that goal. And it may be that this goal needs to be lowered, as some have argued for a 1.5°C goal based on serious impacts appearing at temperatures increases below 2°C.

Nevertheless, we now have a commitment from the president which, if implemented, will start “tapping the brakes” on our carbon emissions relative to 2005 emissions. It’s a start, but we also need to recognize that there’s no “emergency brake” for climate change. The ambition of what our political leaders are suggesting still puts us at grave risk.