In a case now before the US Supreme Court, the Alabama legislature is pushing a radical new theory to reduce minority representation. Will the Supreme Court accept it, throwing out 40 years of science-based protections against racial gerrymandering? Here is my take on the recent oral arguments before the court in this consequential case known as Merrill v Milligan.

First a bit of background. In November of last year, civil rights groups sued Alabama after the state released a proposed Congressional districting map. The lawsuit claimed that the state had violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by drawing districts that dilute the value of Black votes.

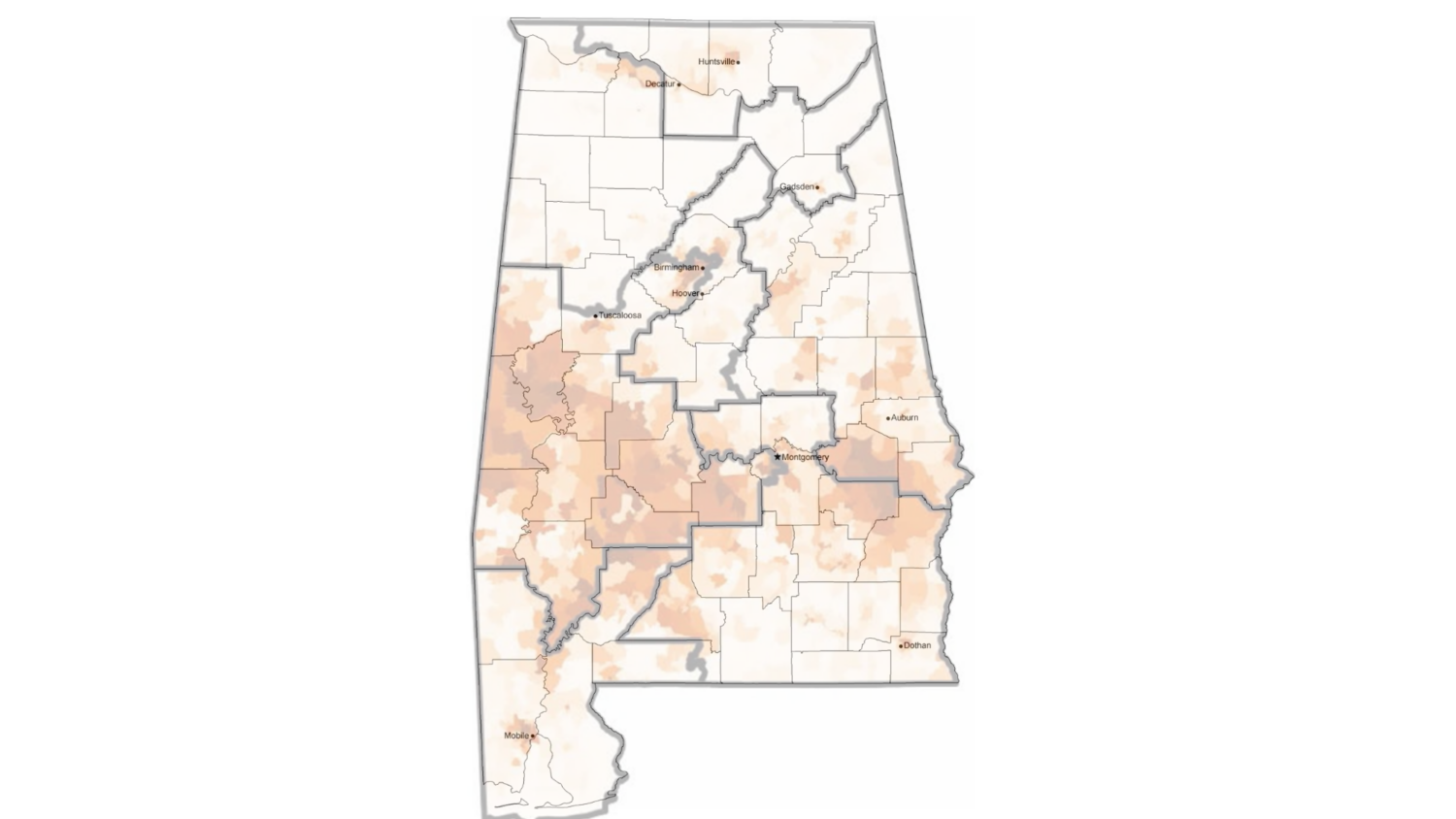

Previously, Alabama’s Congressional map had included two minority opportunity districts out of seven, or 29 percent of the districts in a state where approximately 26 percent of eligible voters are Black, and where elections continue to exhibit racially polarized voting. The proposed new map packs Black voters into one single western district in which 57 percent of the voting age population is Black, likely more than the percentage needed for Black voters in the district to elect their candidate of choice. Meanwhile, the new map splits Black voters in Montgomery and to the southeast into several other districts so that the Black population stands at around 30 percent in each (see Figure 1).

Black voters (shaded population concentration)

in Montgomery and in Southeast Alabama

The case before the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court had ordered a stay on a lower court’s decision that would have required the Alabama legislature to redraw the map in time for the 2022 election. Finally, earlier this month, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case. Defending the new map, Alabama’s solicitor general argued that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is “at war with itself and the Constitution” by requiring states to consider race in the districting process, which he claimed was prohibited by the 14th and 15th Amendments. As evidence to support this claim, Alabama points to the fact that it generated thousands of simulated maps, or ensembles, using computer algorithms that draw districts according to whatever criteria are built into the algorithm, ranging from hard constraints like population equality and contiguity, to softer criteria such as minimizing county boundary splits and maximizing “compactness,” which refers to the geometric shape of districts. As algorithms are adjusted to weight multiple criteria differently, they will produce different maps.

The Alabama solicitor general claimed that if the state relied on a “racially-blind” algorithm (that included no consideration of racial data), their ensembles returned maps with only one majority-Black district, and that two majority-Black districts were generated by algorithms only if they were forced to consider the racial distribution of voters. Justice Alito seemed most interested in this line of reasoning, asking plaintiffs’ counsel how it could be possible that any map with two majority-black districts could be “reasonably configured” if it doesn’t emerge from “a computer simulation that takes into account all of the traditional race-neutral districting factors?”

Two critical errors

The state’s arguments, along with Justice Alito’s questioning, reveal two critical errors. The first involves confusion over the evidence, or what redistricting algorithms actually produce. Statistics produced by redistricting algorithms are designed to reveal the likelihood of intentional gerrymandering, based on a sample of alternative maps. Typically, the characteristics of a proposed map (level of partisan or racial bias, average compactness, etc.) are compared to the range of those characteristics in simulated alternative maps to determine whether the proposed map deviates statistically and significantly from the average characteristic values. In other words, if a proposed map is an outlier on characteristics relative to the sample of alternatives, that is taken as evidence that the mapmaker(s) intended those results.

Plaintiffs’ attorney Abha Khanna was correct to point out that “these simulations…are not any kind of gold standard” and that the results of simulations are a function of “decisions going into the process and about which considerations to take into account and how to quantify them.” Indeed, there is reason to be cautious when using simulation results even when used as intended. My friend and co-author Anthony McGann put it succinctly in our research team’s last book, Gerrymandering the States:

Suppose I cheat at cards by intentionally dealing myself a winning hand. I am not very good at it, and people see me cheating. I, however, have a cunning defense. I hire a mathematician who uses precisely the same logic as is used to argue that gerrymandering is unintentional. My mathematician argues there is a slightly greater than 5 percent chance that an unbiased dealer would have dealt me cards at least as good as the ones I dealt myself. Therefore, I did not intentionally cheat. Of course, this defense is preposterous. The fact that it is plausible that an honest dealer could deal me cards as good as the ones I got is irrelevant. It does not prove that I did in fact get them honestly. My opponent’s case does not depend on the cards I received being implausibly good, but on the fact that I was seen cheating.

But what Alabama is trying to get away with is even more preposterous. They would have us believe that, after explicitly excluding racial data, their “blinded” simulations should be used as a benchmark for maps that are, by their circular definition, racially neutral. As both the solicitor general and Justice Alito acknowledged, their theory rests on a premise that racial blindness is the equivalent of racial neutrality in the generation of districting maps. This represents a second, deeper error.

Racial blindness is not racial neutrality. The key here is that the Voting Rights Act is explicitly designed to ensure representation for voters of color in a country where racially polarized voting is persistent. According to Section 2, for a voting standard, practice, or procedure to be race neutral, it must not deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group. In fact, most of the discriminatory laws that Section 2 has been used to dismantle have been racially “blind” in design: inequality in the apportioning of populations to districts, use of at-large bloc voting systems, failure to comply with national voter registration laws, and the like. Under the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution, Congress is given the power to legislatively protect voters from racial discrimination in voting. Those practices were outlawed because, even though blind, they were not racially neutral in the context (racially polarized voting) in which they operated. They failed to provide voters with an equal opportunity to determine electoral outcomes. The key here is that the racial neutrality of any voting standard or procedure must be judged by its empirical impact on the future representation of voters, not whether race is explicitly incorporated into its design.

The very fact that we hope to achieve multiple standards simultaneously through districting means that standards will often be in conflict with one another and that there will be tradeoffs to consider. The standard of compactness, for example, is a “racially blind” statistic derived using a wide variety of geometric measures, that may or may not be racially neutral. My research team is one among many that have demonstrated how highly compact districts can violate voting rights by packing homogenous voters into districts where they waste votes relative to more efficiently apportioned populations. Compactness may be valuable for other reasons, but there is no way to know whether overly compact districts are discriminatory until we empirically estimate the impact of a given districting configuration on future voting patterns. Plus, it important to note that there is no constitutional right to compact districts.

What the science shows

What current empirical data do tell us is that excluding racial geography from districting criteria is likely to result in districts that require racial minorities to build larger coalitions with white voters, and reduce the number of districts where voters of color can effectively choose their preferred candidates. Moon Duchin, a leading mathematician engaged in ensemble simulations, has also concluded that “race-blind districting would devastate minority political opportunity no matter how it is deployed, just due to the mathematics of single-member districts.”

Professor Duchin’s point is worth further explanation: In electoral systems where only one candidate and one party per district receive representation (i.e. win), electoral outcomes inherently discriminate against numeric minorities (losers) in those districts, resulting in a “seat bonus” for the largest voting bloc in the state. Imagine the extreme example of an Alabama districting simulation that happened to produce seven Congressional districts that looked like the state as a whole, a map in which roughly one quarter of voters in each district were Black. Under such a map, if racially polarized voting persists, Black voters would never elect a single representative, and the white voting bloc would always win every seat.

For nearly forty years, the procedure used to identify and remedy this type of racial vote dilution in redistricting cases, known as the Gingles test, has taken the single-seat system as a given. And given the discriminatory potential of this type of “racially blind” system, the test begins by taking racial geography into account. Its first requirement is to identify whether a “reasonably configured” district would allow a minority group to elect a candidate of their choice. The ”racially-blind” approach advocated by Alabama would replace this contextually sensitive, evidence-based approach with a sweeping, radical misinterpretation of the Voting Rights Act and a rejection of the constitutionally protected principle of political equality as applied to elections.

What’s next

Fortunately, in oral arguments, it did not seem as though a majority of the Court accepted Alabama’s radical theory. However, it is likely that the conservative majority will uphold Alabama’s discriminatory map, by rejecting plaintiffs’ claim that a second Voting Rights Act district could be “reasonably configured” or compact. Following Justice Alito’s lead, they may decide that compactness trumps racial equality, but only in this specific context, without attempting to justify the more sweeping claim that blindness is equivalent to neutrality.

Unfortunately, even if the Court makes such a narrow ruling in this case, its use of compactness or other criteria as an excuse to allow discrimination will represent another blow to the integrity of the Voting Rights Act and the established science used to protect voters of color in a country where racially polarized voting is persistent.

In the face of an increasingly hostile Supreme Court, defenders of voting rights need to identify and advocate for alternative remedies for protecting political equality. No electoral system can guarantee the right to cast an equally weighted vote, but the adoption of multi-seat, proportional electoral systems, which can be calibrated to be race-neutral, would greatly reduce the incentive and impact of various forms of gerrymandering. Other innovations such as candidate list systems, and the allowance of alliance or “fusion” ballots that allow multiple parties to support those lists, may also work protect political equality and voter choice while incentivizing the formation of multiracial coalitions. There are a number of institutional options, some of which may already have the support of conservative justices, that have been shown to outperform our single-seat district system in terms of accurately reflecting the racial composition of the electorate. It is past time to start taking these reform options more seriously.