Some of you may have been following the news about the drought in the Western United States and probably saw headlines about a study finding that the last 22 years have been the driest in the Western U.S. in at least the previous 1,200 years. It says “at least” because that is how far back the reconstructed data goes. It could be longer. Let’s unpack what is in that research to catch up with the state of the current drought, to analyze how it relates to California’s Central Valley, and to see what we can expect from another year of drought.

The last 22 years have been the driest in at least the last 1,200 years

To fully grasp what is happening, we must recognize different types of droughts and understand the available data. Here we are talking about drought conditions as measured by soil moisture—or the lack of it—and the data is extraordinary. In 2020, scientists reconstructed soil moisture data for the last 1,200 years. This was accomplished by creating a correlation between tree-rings and soil moisture, which is a standard measure of drought.

Tree rings record the growth of trees year after year and for a Western States climate in the U.S., the wider the tree-ring, the more water (soil moisture) the tree had available that year. By correlating this information with recorded climate data that has been measured over the past 120 years, it is possible to link the width of tree-rings to drought conditions. They have then applied that tree-ring width to moisture relationship to data from much older trees. The result is an incredibly precise record of soil moisture over 1,200 years.

Two years ago, when the study was published, it revealed that this dry period was the second-worst in the past 1,200 years, exceeded only by a megadrought (a dry period lasting for decades) in the late 1500s. After two more dry years (2020, 2021), the current period of dryness in the Western United States broke that record, and the last 22 years have now been the driest in at least the last 1,200 years.

Climate change responsible for about 40 percent of the intensity of current megadrought

Another highlight of the study is the role of climate change in the current megadrought. Without climate change, we would still be having a drought but, according to the study, its severity would have been only about 60 percent of what it is. In other words, climate change is responsible for about 40 percent of the intensity of the current drought.

Drier conditions are mainly driven by increased evapotranspiration from rising temperatures and snowpack melting earlier in the season, creating longer dry periods. This adds to the evidence of the significant role that rising temperatures alone—caused by heat-trapping gases—play in shaping climate conditions and their impacts.

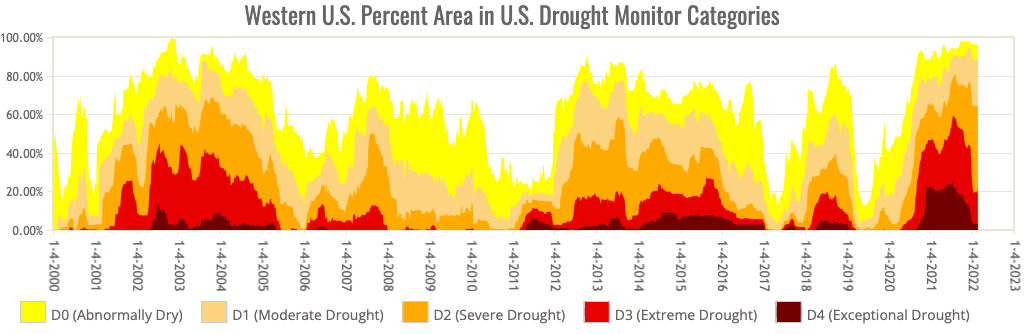

While the West has had intense rain events over the past 22 years, the precipitation has been insufficient for soil moisture to recover to what would be considered normal conditions (Figure 1). Despite some wet years like 2005, 2010, and 2017, soils have been unable to recover from a soil moisture deficit since the year 2000, leading to the current megadrought.

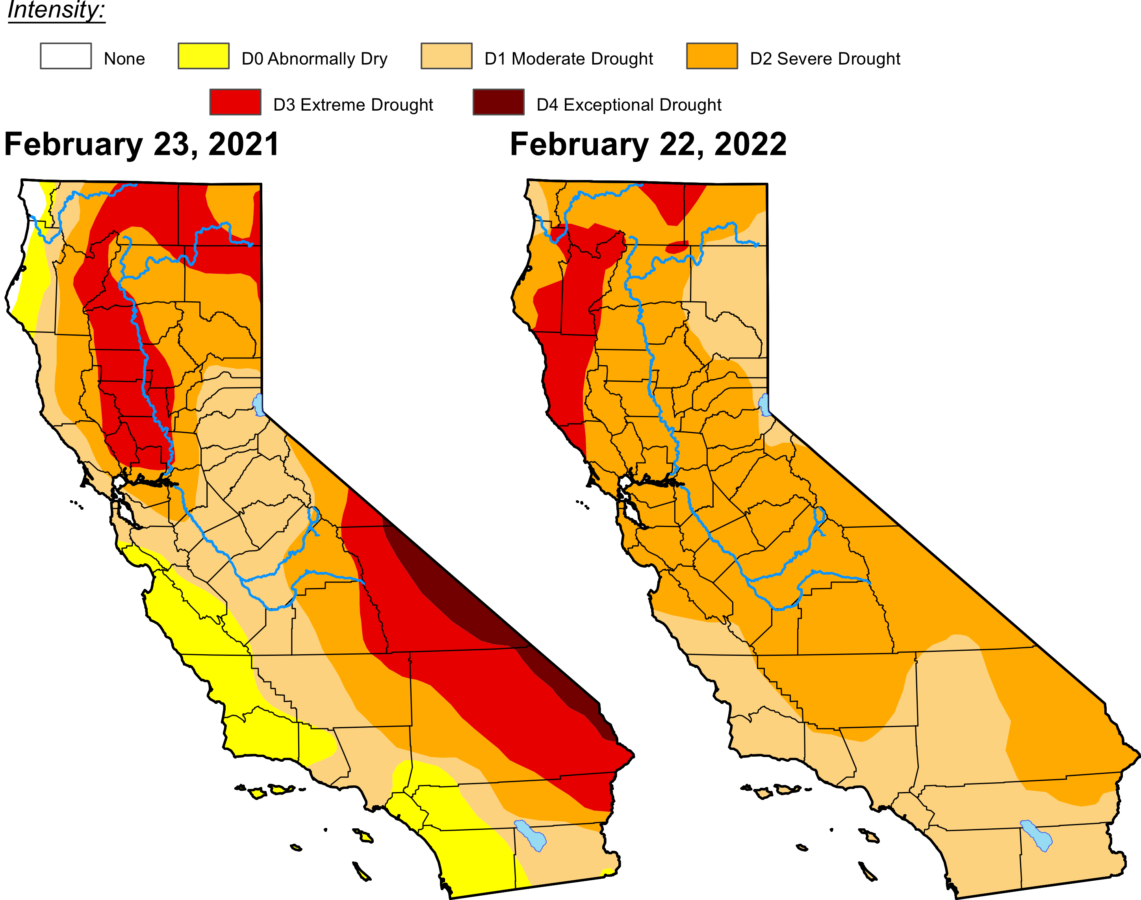

Entire Central Valley is under severe drought conditions, compared with about half of it this time last year

Let’s compare drought conditions from a year ago with now (Figure 2). A year ago, 30 percent of California’s area was experiencing extreme drought conditions, and exceptional drought conditions (the worst drought category) were looming in the southeast of the state. This year, extreme drought covers close to 7 percent of the state in the northwest, mainly in Trinity and Mendocino counties, and exceptional drought conditions haven’t been observed yet. Still, the whole state is at least under a moderate drought category, and we haven’t yet reached May, the beginning of California’s dry season.

While the state as a whole is in better condition than this time last year, the Central Valley is actually more drought stricken. The entire Valley is already under severe drought conditions, compared with “only” half of the Valley at the beginning of March last year. This is the region of the state hardest hit by droughts, and it is already doing worse than last year.

This means that crop or pasture losses, water shortages, lowering groundwater levels, and water restrictions will continue for another year. If miraculous rain doesn’t come during March, extreme and exceptional drought conditions — and drought impacts—will intensify as temperatures rise during spring and summer.

Snowpack, which is a vital water source for the state and in particular for the Central Valley region, was at 61 percent of average a year ago, compared with 63 percent of average today, so not a significant difference. October 2021 was one of the wettest Octobers, then November 2021 one of the driest, December 2021 one of the wettest, and January and February 2022 among the driest. In December, snowpack was at 160 percent of the average for that time of the year, and in two months of no significant precipitation, the snowpack is already almost 40 percent below average.

Dry periods are occurring at a rate that not only impedes soil moisture recovery but also inhibits our communities from recuperating and keeps our institutions in a state of reaction rather than prevention. In recent years in the Central Valley, there have been hundreds of wells going dry, hundreds of thousands of acres of idle cropland, fish harmed, hydropower declines, and increasingly intense and severe wildfires. In 2021 alone, the drought has directly cost the agricultural sector an estimated $1.2 billion (including $184 million in greater pumping costs), 395,000 in idled cropland, and roughly 8,745 full and part-time job losses, according to a recent UC Merced report.

From my perspective, these impacts are heavily derived from climate change but also from human decisions that lead communities in our society to become more vulnerable and less resilient against droughts.

Increasing the inflexibility of water systems by growing more perennial crops is taking us in the wrong direction.

While every individual has a role to play on reducing water use to lessen drought impacts, industrial agriculture has the biggest role of all. In the San Joaquin Valley, the top 6 percent largest irrigated farms account for 60 percent of the irrigated acres.

The few have been mining the prosperity of the Valley and further increasing the vulnerability of smaller farms and their communities for short-term profit. The same UC Merced report quantifying ag losses due to drought shows that tree nut acreage has been steadily growing from about 600,000 acres in 2000 to nearly 1.8 million acres in 2020.

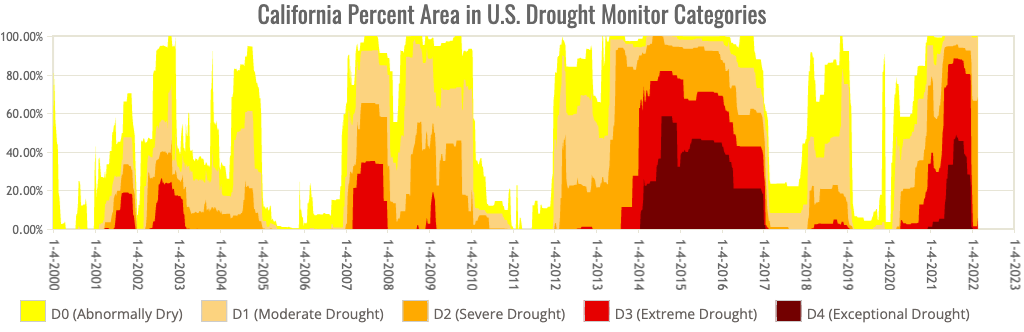

Considering how dry California’s last 22 years have been (Figure 3), it is easy to conclude that the industry responds more to market forces than drought conditions. The heavy expansion of perennial crops reduces the flexibility of the system because they become a compromised water demand for decades, compared with seasonal crops that could be planted or not depending on water availability of a particular year. Another big culprit of water use in the valley is animal agriculture and, in particular, the dairy industry, a topic that would require its own blog post.

As drought intensity lowers surface water availability in rivers and lakes across the state, groundwater pumping increases. That leads us to a vital topic, groundwater sustainability.

Groundwater sustainability

Before the current megadrought began two decades ago, California already had a historical groundwater overuse problem (Figure 4). In many areas, like the San Joaquin Valley, groundwater pumping has been greater than what naturally replenishes it for the past 100 years. The groundwater decline is not that surprising, considering that there were virtually no groundwater use regulations before the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

As part of SGMA, hundreds of local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) were formed and tasked with developing Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs), which describe their path for reaching groundwater sustainability by 2040. Before SGMA, it wasn’t lousy groundwater management; it was virtually no management at all, with the exception of some adjudicated areas.

Unfortunately, many Groundwater Sustainability Agencies have been dominated by the historic powers in the region, and the implementation of many plans as currently developed would favor those with the strongest voices, the most money, and the most political power. While SGMA included novel stakeholder engagement requirements in an attempt to give voice to the drinking water and environmental users of groundwater, most GSAs botched this and continued with business as usual.

In addition, a less than full consideration of groundwater quality issues affects hundreds of thousands of people across the Valley. Climate change projections are not being sufficiently incorporated. A common trend is that most GSPs haven’t considered future scenarios of extremely hot and dry weather, which is not something far in the future, but conditions that we are experiencing today.

It worries me that some of these plans may be overestimating future water availability and underestimating future water demands. So, now that these GSPs are out, they indicate that there will now be some management, but unfortunately, in many cases, it will be poor management.

The bottom line is that: a) the law should be strengthened to require better consideration of climate science and stronger protections for the most vulnerable communities in the state; and b) the law needs to be implemented. For example, climate change provisions are being met, they’re just not good enough and also stakeholder engagement requirements are part of the law but there are multiple areas of improvement to equitably consider all beneficial users.

Without groundwater regulations, the agriculture industry has been able to mine everyone’s water for their profit and benefit. By the way, I’m not talking about small family farms and generational farmers with love and attachment to the land and the culture of growing food; I’m talking about Big Ag investors, whose main motive is profit, who buy out smaller farms, and could eventually find another place to mine.

I recognize that we all benefit from agriculture and that it is part of the history and culture of the Valley. So, to be clear, I’m not against agriculture, I’m against greed, and I’m against the inflexibility and the inequities that water-intensive crops like monocropped almond and other similar nut trees exacerbate. So, what can we do about it, and what are some ways to move forward? We’ll attempt to address some of these questions in future posts in this series.