It is early September, and we are late into what we at UCS call Danger Season, or the period between May and October when climate change is increasing the frequency, intensity, and/or duration of extreme weather events such as heat waves and wildfires. And indeed, this week over 6 million people experienced temperatures above 110°F (43°C) in California’s Central Valley, the most important agricultural region in the United States.

I live in Merced, a relatively small city in the Valley, and as we go through the worst heat wave in the region’s history, I want to describe what 115°F (46°C) feels like and what climate change-fueled extreme temperatures could mean for this region.

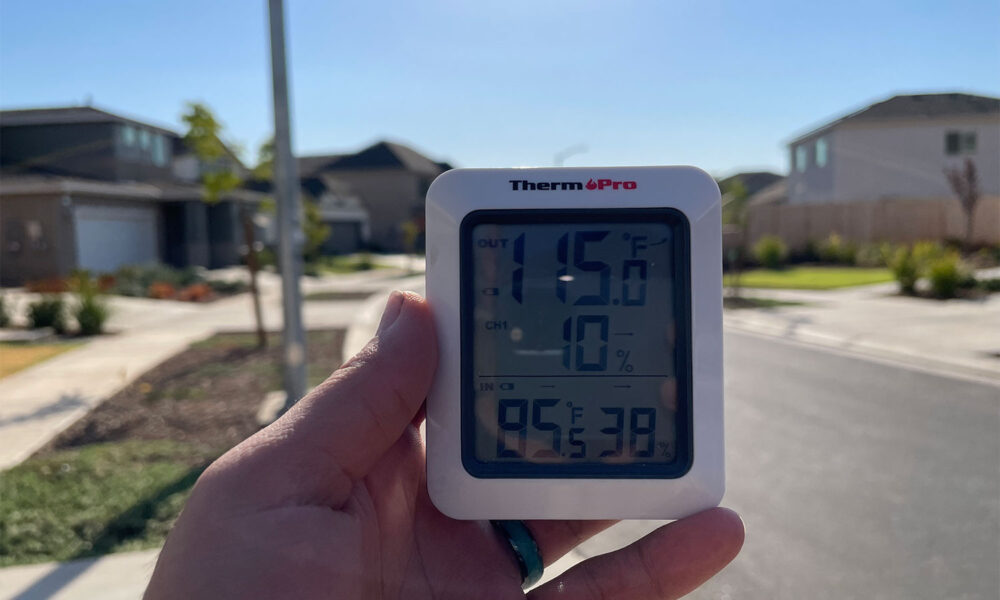

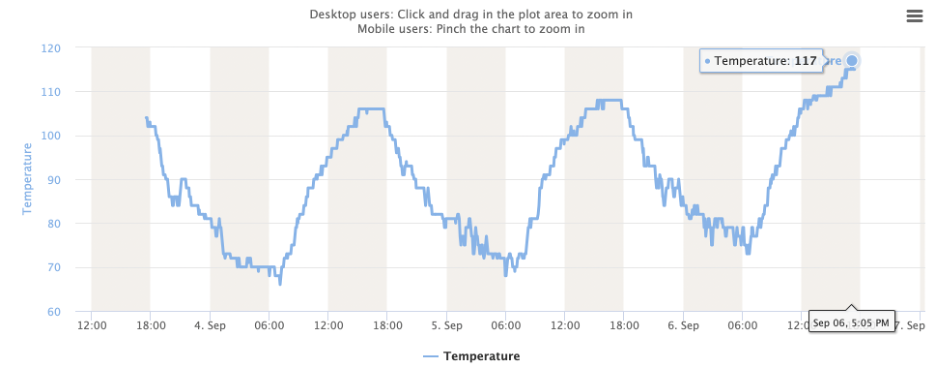

As recorded by the National Weather Service, the maximum temperature on Tuesday reached 116.6°F, breaking the previous record of 114°F from 1925. My outdoor thermometer agreed with that reading by registering 116.6°F at 5:15 pm, and it was above 100°F from 10:45 am to past 9:00 pm; that’s over 10 hours with temperatures above 100°F. Other regions of the world have experienced temperatures like these before, and while it may not be a surprise for some cities to reach 115°F, it is certainly never fun, and never without its toll on people, nature, and infrastructure.

The most impacted are outdoor workers and the many families in low-income rural communities across the Valley that don’t have air conditioners or can’t afford to pay for their use. Many people in these families are farmworkers who pick the produce going to our tables. Stories of farmworkers picking produce under extreme heat are numerous, as the United Farm Workers (UFW) often documents.

A day in the (work) life of a Central Valley farmworker

So imagine you are a farmworker in a Central Valley community on such a day. The lowest temperature last night was 75°F, and you wake up to go to work before the sun comes out. Your workplace is a dusty agricultural field, with little to no shade, and it has what feels like infinite rows of crops with produce for you and your co-workers to pick up, package, and load onto a truck.

As early as 9:00 am it’s already 90°F and your body is sweaty and dust sticks to your skin giving a sandy, not a comfortable feeling. The heat rises as well as your heart rate as your body compensates to adapt, but the rest, water, and shade breaks your employer is required to give you are short, and you also want to meet your quota because you get paid by how much you pick.

The heat keeps rising, and you may need to choose between going home and not getting paid or risking your health when it is too hot to work. Your feet get hot. You left your tools under the sun during the break, so they are hot too. As the day goes by, your body and mind get tired. Eventually, the work for the day ends and you start your way back home. It is not uncommon to feel judging eyes looking at you on the way home because your clothes are dirty and you look tired.

When the heat reaches its peak around 5:00 pm you are back home with your loving family, friends, or roommates, or you may feel lonely because your family is thousands of miles away in your home country. The AC doesn’t work (or you don’t run it because there go your wages), but at least the pedestal fan pointed directly at your body and some cool water help. Still, it’s going to be hard to fall asleep in this heat even when you are tired from the workday. After another restless night, the sun will come up soon, so you better get up before it gets too hot to do it all over again. It’s harvest season and someone needs to pick that harvest up.

On Tuesday–the hottest day of the year (so far)–in Merced, I wanted to put myself in the shoes of the many farmworkers bearing these conditions. I turned off my AC, opened a window, and tried to keep going with my day. I was already sweating when the thermometer reached 85°F even though I was only working on my computer. I decided to take it one step further and went outside, gardening in my backyard at 115°F.

I got the first sensation of the searing heat when I opened the door to go out. It’s almost like opening a hot oven and sticking your face inside. It first hits your face and then the rest of your body, except that the heat is constant and doesn’t dissipate as when the oven’s heat comes out. Under the sun, the sensation is stronger because solar radiation is heating up your body.

After less than an hour I was already wet with sweat, dust on my clothes and body, and I managed to burn my hand when I accidentally grabbed the metal part of a shovel that had been under the sun. I was monitoring my heart rate, which after a few minutes under the heat was constantly above 160 beats per minute. Eventually, I realized how silly I was pretending to put myself in the shoes of people who have to work on farms for a living. It was simply not comparable to being outside for only one hour of one day and knowing that, at any time, I could go inside my home to cool off.

As silly as my “experiment” was, my respect, admiration, and gratitude for farmworkers and all outdoor workers grew even more. I felt how even a small shaded space makes a big difference, as well as rest and having cold water to drink. I also realized that one of the hardest moments was when I went back into my room and because I had turned off the AC, it wasn’t much better than outside. When I thought I had finished my “experiment,” I realized that the effects from the heat and the sun on my body continued after reaching shelter; I felt slightly dizzy and weak and didn’t fully recover until a couple of hours after rehydrating.

Later in the day, I confirmed that extreme heat affects energy and food security, as well as public health. At around 4:00 pm, an emergency alert went off on my phone. The California Office of Emergency Services (CalOES) was asking everyone to turn off nonessential electric appliances because the capacity of the electric grid was reaching its limit. As the heat wave was warming the homes of millions of people, electricity demands for cooling them off rose dramatically. With climate change, extreme heat days are becoming less surprising and more common and heat waves are already coming faster, stronger, and becoming more persistent.

One of the biggest problems is that as long as global heat-trapping gas emissions don’t stop, extreme heat and heat waves will continue to break records every summer for the foreseeable future. That makes the renewable and clean energy transition the only long-term solution.

In the meantime, there is an urgent need for stronger federal outdoor workers’ protections that ensure common-sense measures like access to breaks in shaded areas, sufficient rest time, available cool fresh water, and training for workers and supervisors to recognize and act on the symptoms of heat stroke or heat exhaustion. That’s what the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act–named after a real farmworker who died from workplace extreme heat exposure–will provide for outdoor workers.

Other measures would require paid days when conditions are too hot to work so that outdoor workers don’t need to choose between their health and livelihoods. Government programs for air conditioner installation, home weatherization, and economic assistance to pay utility bills need to be adequately funded and target the most vulnerable people. Also, cities can increase the number of cooling centers and strategically locate them for people who most need them, which in an emergency situation could be any of us.

And Congress needs to pass the National Climate Adaptation and Resilience Strategy (NCARS) Act so we can all have a national plan to manage compounding hazards.