Deadly heatwaves, extreme drought, food and water shortages, catastrophic flooding, rapidly intensifying tropical storms, raging wildfires—around the world, climate change is exacerbating extreme conditions and their harsh toll on people and ecosystems.

It’s fueling “Danger Seasons,” when these impacts are at their peak and are also increasingly likely to collide with one another. And year-upon-year of these danger seasons are becoming the crushing “new normal” for all too many. The world must rapidly scale up measures to adapt to climate change alongside efforts to sharply cut heat-trapping emissions to limit climate change. But right now, policymakers are falling far short and richer nations in particular bear significant responsibility to do more.

An “atlas of human suffering”

According to the latest IPCC working group II report, today over 40 percent of the world’s population is living in contexts that are highly vulnerable to climate change. The fearsome toll of climate impacts is already clear, leading U.N. Secretary General António Guterres to call the report an “atlas of human suffering.” Already this year, we have seen the leading edge of the 2022 danger season. My colleague Kristy Dahl has detailed the impacts of recent danger seasons in the U.S. including wildfires, drought and heatwaves.

Here is just a snapshot of what we’ve seen elsewhere around the world in 2022 so far:

- An early, intense heatwave in India and Pakistan starting in March, with temperatures reaching as high as 122 F, has caused at least 90 deaths and untold suffering. An attribution study shows that climate change made this heatwave 30 times more likely. Another from the UK Met Office shows that this type of heat wave has been made 100 times more likely because of climate change. In addition to the acute public health toll in places where most don’t have access to air conditioning and many work outdoors, the heatwave has also severely affected wheat and other crops and dealt a devastating blow to farmers’ livelihoods. As the IPCC WGII chapter on Asia shows, the risk of these types of deadly heatwaves will grow with worsening climate change.

- Eastern Africa is enduring an extended drought with catastrophic consequences for food security and livelihoods. A joint statement from meteorological and humanitarian organizations last week called the “extreme, widespread, and persistent multi-season drought” affecting Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia “unprecedented.” Over a million people have been displaced, nearly 17 million people face high acute food insecurity including many severely malnourished children, and millions of livestock have died.

- Catastrophic floods hit South Africa in April this year, when two days of intense rainfall caused at least 435 deaths and billions of dollars of damage. An attribution study shows that climate change has doubled the chances of the type extreme rainfall that caused this disaster.

- Deadly floods and landslides in Brazil in May, triggered by heavy rain have killed over 90 people.

- Three tropical cyclones hit Southeastern Africa, affecting Mozambique, Malawi, Madagascar and Zimbabwe in January and February, triggering heavy rainfall and flooding. Climate change likely contributed to an increase in the likelihood and intensity of heavy rainfall associated with these tropical cyclones. Underlying factors including poverty and a prolonged drought in Madagascar worsened the impacts on people affected.

- Wildfires have broken out in Siberia, which is one of the fastest warming parts of the world and where hotter, drier conditions have fueled record-breaking fire seasons including in 2021.

- Hurricane Agatha, the strongest hurricane to make landfall in May in the eastern Pacific, came ashore in Mexico last weekend causing mudslides and killing at least 11 people.

As summer in the Northern hemisphere advances, communities must be ready for more dangers. Past years have brought wildfires, heatwaves and floods in Europe; heatwaves, floods and intensifying typhoons and cyclones in Asia and the Pacific; heatwaves, drought and wildfires in Brazil and other parts of South America, just to name a few of the climate impacts already unfolding. In the Southern hemisphere, danger season often coincides with the summer months there—for example, the record-breaking bushfires that Australia has endured in recent years.

Adaptation—and its limits

There is no question that we are now in a climate crisis and must adapt to those changes that are inevitable. According to the IPCC WGII report, “Increasing weather and climate extreme events have exposed millions of people to acute food insecurity and reduced water security, with the largest impacts observed in many locations and/or communities in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, Small Islands and the Arctic (high confidence).”

However, the current approach of treating climate extremes as one-off disasters instead of part of a bigger, dangerous trend is leaving communities, policymakers and emergency responders reactive and ill-prepared. The physical and mental toll on communities being repeatedly hit, and on first responders, is immense. In some cases, initial policy responses have been maladaptive and short-sighted, out of step with the accelerating risks highlighted by the latest science. Moreover, in many parts of the world, poverty and structural inequities rooted in colonialism, unfair economic systems, and discrimination are exposing some people to heightened risks.

Danger season, together with ongoing slow-moving disasters like sea level rise, is pushing people and ecosystems to their limits in many places. These climate-fueled disasters are undermining economic development and hard-won gains in public health and poverty eradication. They are also intersecting with other challenges like the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the wider food, energy, and economic repercussions of the war in Ukraine. Some of the most extreme climate risks are, and will increasingly, lead to mass displacement of people from climate danger zones.

If we fail to sharply curtail global heat-trapping emissions, that will only increase the misery and harm, especially for those most vulnerable and those who have the fewest resources. The science is clear that the impacts of climate change will accelerate rapidly, and in a non-linear way, as the global average temperature rises beyond 1.5C. Many changes are irreversible or will be very long-lasting.

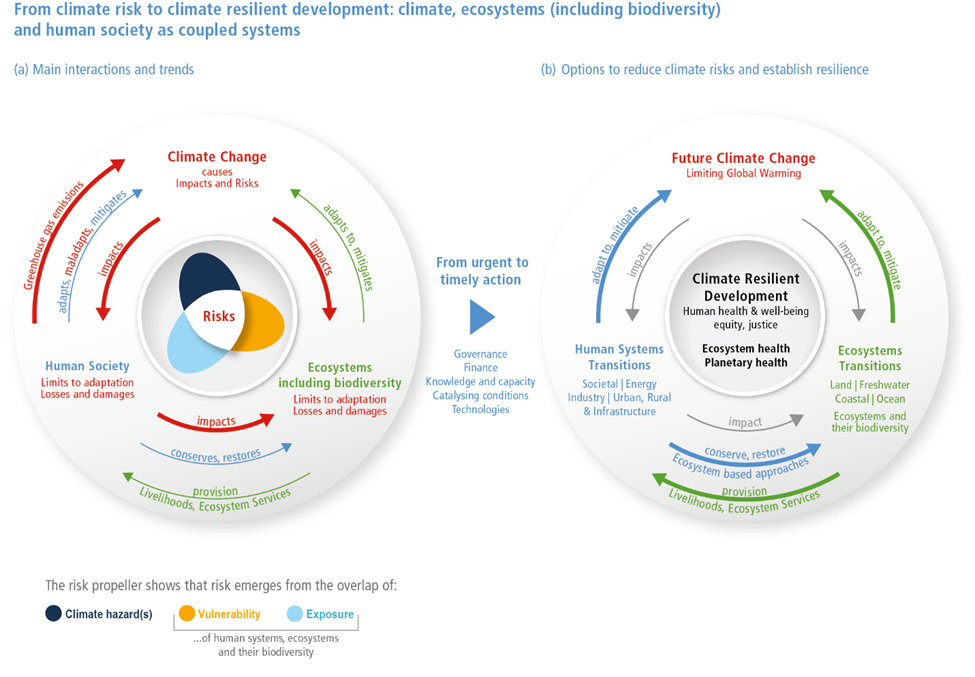

As the IPCC working group II report put it, many communities are running up against hard and soft limits to adaptation—the hard limits being physical and the soft ones being a lack of resources and political will. But we can and must take actions now to save lives, limit harms and ensure climate action is aligned with sustainable development goals.

Urgent actions required

Richer nations including the United States, whose heat-trapping emissions are the primary contributor to climate change, must do much more to provide resources and funding to lower income countries to help them adapt to climate change. This should not be viewed as voluntary “humanitarian aid,” to be provided at the whim of richer countries; this is their ongoing moral and ethical responsibility. It is also a critical part of their commitments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement.

Loss and damage from climate impacts that are beyond the limits of adaptation—such as loss of land to rising seas—are also a growing reality in many places. Climate vulnerable, low-income nations have long been calling for this issue to be addressed within the framework of international climate agreements, and yet have repeatedly faced obstacles including at COP26 in Glasgow last year. The U.S. and other richer countries must commit to setting up a Loss and Damage Finance Facility at COP27 this year in Egypt, with funding flowing shortly thereafter. There is also growing interest in climate litigation efforts, also highlighted in the IPCC WGII report.

An underappreciated but crucial investment is upgrading early warning systems using the latest science and technology, coupled with outreach to communities at risk. Early warning systems and action plans for heatwaves, tropical storms and other hazards are literally lifesaving. The United Nations has recently set a target for all people to be protected by early warning systems within five years and the World Meteorological Organization has been tasked with leading this effort.

The US Congress must step up to ensure that the upcoming appropriations process for the FY23 budget includes robust funding for international climate finance. President Biden’s PREPARE initiative has some important elements to help advance climate resilience but without adequate funding, those efforts will fall far short. And, of course, the US must secure policies to deliver on its commitment to cut its heat-trapping emissions 50-52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. The budget reconciliation bill that has stalled in Congress is a critical down payment toward meeting that goal and must be complemented by robust carbon pollution standards for power plants and vehicles and for limiting methane emissions from the oil and gas industry.

Climate justice in a season of danger

It’s well past time to stop denying the severity, scale and urgency of the climate crisis. Here in the United States, and around the world, the challenges are common, and the solutions are similar. “Danger Seasons,” which are quickly morphing into danger years and decades, require a robust policy response and a significant commitment of funding and resources now, directly benefiting those most at risk.

While climate change affects us all, the harshest burden is falling on those who have the fewest resources and have contributed the least to the problem. That’s why solving the climate crisis is inextricably connected to solutions centered in equity and justice. We don’t need adaptation measures that are simply geared toward propping up business-as-usual, and preserving privilege, wealth and a way of life that benefit an elite few. True climate resilience requires transformative changes that advance fairer economic systems and governance, where all people and communities have the opportunity to thrive in the face of the enormous challenge of climate change.

When lives are at stake, when entire communities, cultures, species and land areas are threatened—as they are right now—we have to reach deeper and do better for all of humanity and the planet’s precious ecosystems.