A new UCS study released today, Looming Deadlines for Coastal Resilience, shows that risks are growing to vital infrastructure and services that millions of people in coastal communities depend on as global sea levels rise in the coming decades. This will have wide-ranging implications for public health, safety, education, and well-being, and for coastal ecosystems and ways of life. Policymakers and public and private decisionmakers must act with urgency to take protective action now, working together with communities.

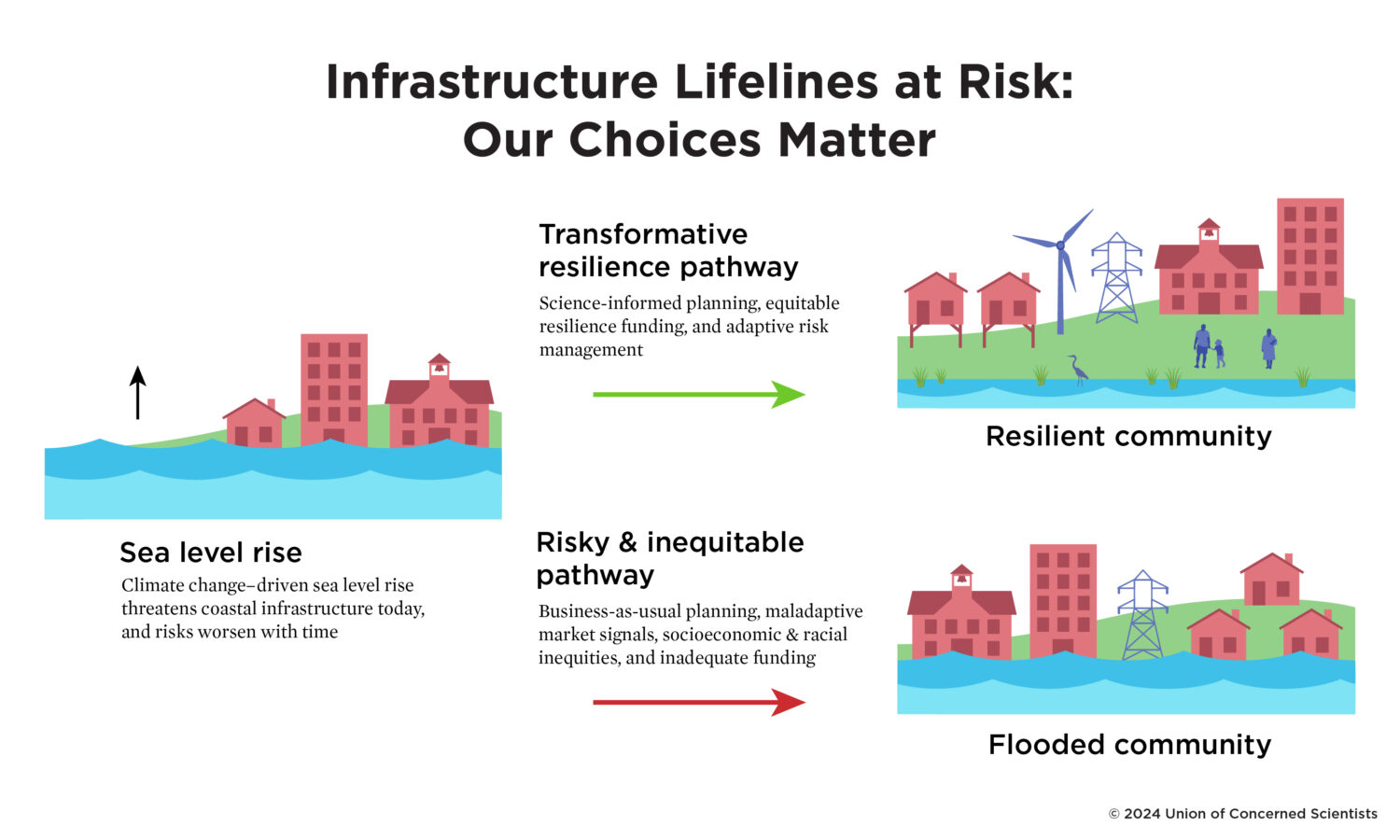

Decisionmakers, planners, and technical experts involved in funding, developing, designing, insuring, operating, and maintaining infrastructure must take immediate steps to safeguard critical infrastructure and ensure a more transformative path to true resilience over time, instead of business-as-usual maladaptive choices (see figure below).

Our study highlights six important recommendations to enhance resilience to coastal flooding for coastal infrastructure:

1: Use science and innovation to plan for near- and long-term risks

Across communities, there is a shared need to assess physical exposure and vulnerability to sea level rise risks and to develop plans to address them. Scientific projections of sea level rise and coastal flooding should be incorporated into all infrastructure investments, construction, operation, and maintenance. Local and state governments should conduct localized scientific risk and vulnerability assessments of critical infrastructure, including the potential for cascading vulnerabilities of interconnected infrastructure. They should develop comprehensive climate resilience plans to mitigate those risks and build inclusive processes to regularly update them.

Owners and operators of infrastructure, together with engineers and other experts, should develop action plans to address the risk of sea level rise, with public and private resilience planning being appropriately coordinated. And these plans should be regularly reevaluated based on the latest science and for robustness across plausible future scenarios.

New and improved infrastructure should be designed—and existing infrastructure upgraded—to meet stringent protective flood standards and engineering and building codes that account for rising seas and that remain effective for the assets’ expected lifetimes. In addition to measures onsite, community-wide measures, including beneficial land zoning and protection of natural flood mitigation assets, like wetlands, are extremely valuable and must be prioritized.

With sea level rise accelerating and significant infrastructure investments flowing through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the next 10 years are crucial to make meaningful progress in building climate resilience and safeguarding those investments from flooding. Congress should build on the Biden administration’s National Climate Resilience Framework by enacting a comprehensive national resilience strategy that provides guidance and technical assistance, and helps coordinate and target federal resources for state, regional, and local adaptation efforts.

2: Scale up public and private sector funding for infrastructure resilience

US infrastructure has long been woefully underfunded and routinely assessed as requiring attention, and sea level rise exposes and exacerbates those vulnerabilities. Public and private investments in infrastructure resilience must be scaled up across the board. Data from the National Institute of Building Sciences show that investing in retrofitting infrastructure such as wastewater facilities and electric substations has a benefit-cost ratio as high as 31 to 1.

State and federal policymakers must marshal funding for the proactive protection of infrastructure and prioritize resources for less wealthy and historically disadvantaged communities. Although existing federal funding is helpful, it falls well short of what is required and must be better aligned with projections of future flood risks.

Congress should also consider public-private opportunities, such as through a national resilient infrastructure bank. Funding raised through taxes, fees, utility rates, municipal bonds, and loans will all likely need to play a role, given the scale of the challenge. Litigation pathways could help make polluters fund climate resilience in addition to paying their share for damages, as part of holding fossil fuel companies accountable for their outsize role in the climate crisis.

Many critical infrastructure assets, including those in the power and wastewater management sectors, are owned, operated, or managed by private-sector entities, which makes their role essential in planning for and investing in climate resilience measures. Public utility commissions should require that utilities account for climate risks and make prudent investments in resilience while safeguarding the interests of ratepayers and protecting low-income households from potential rate spikes related to adaptation investments.

Market signals and incentives must be science-informed to prevent maladaptive choices and promote resilient outcomes. This is creating specific challenges in the context of insurance. In addition to climate impacts on homes and homeowner’s insurance, power sector assets, wastewater treatment plants, and public housing are also at risk of flooding from rising seas. These assets, too, require insurance—and that insurance is about to get more costly or hard to come by in some places, if it isn’t already.

My colleague Shana Udvardy also lays out important recommendations to boost infrastructure resilience to climate impacts as this summer’s Danger Season of climate extremes gets under way.

3: Reduce historical inequities and prevent future harms

Our results show that communities already disadvantaged by historical and present racism, poverty, and other factors face a disproportionate burden of the nation’s current and future risks to coastal infrastructure. In some cases, these communities are in particularly flood-prone areas because economic factors, colonialism, racism, and deliberate policies such as mortgage redlining denied them access to, dispossessed them of, or forcibly moved them from more desirable areas on higher ground. Often, these same communities have also borne the health impacts of polluting and risky infrastructure intentionally sited within or near them, such as Superfund and other toxic or hazardous contamination sites. Worsening coastal flood risks add an additional layer of risk and compound harm.

Policymakers and decisionmakers should undertake resilience investments that limit further burdens on these communities; ensure that historically disadvantaged communities are prioritized for resources, including through effective implementation of the Justice40 Initiative; reduce barriers to funding and resources; reflect risk aversion through Office of Management and Budget guidance; and enable better outcomes. Communities should also have a direct say in the decisions that affect them, and policymakers must respect Tribal sovereignty. Decisionmakers must ensure that harmful histories of racism and inequities are not repeated as we invest in upgrading and building new climate-resilient infrastructure.

4: Protect affordable housing and open just pathways to retreat, where necessary

Public and affordable housing represents the single most at-risk category of infrastructure assets evaluated in the UCS Looming Deadlines analysis. Any loss of these units will add to the already acute crisis in the availability of such housing, driven by decades of under-investment and racial discrimination. Repeated flooding can also cause structural problems, mold, and other hazards to residents. All levels of government must invest in the protection, renovation, and construction of climate-resilient and energy-efficient affordable housing.

In places most highly exposed to flood risks, multiple critical infrastructure assets as well as homes and businesses may be in jeopardy, making the task of protecting them all eventually untenable. In such cases, decisionmakers may need to initiate hard conversations about managed retreat of entire communities. These discussions should include both resettlement resources for displaced communities, and resources and infrastructure investments for communities that receiving the displaced. Crucially, all these decisions must take place within a broader institutional framework that provides for meaningful engagement with communities and a human rights–centered approach to addressing climate-related displacement.

5: Start informed, flexible, adaptive planning now for later-century potential outcomes

Both the emissions choices we make over the next several decades and ice sheet dynamics will have significant bearing on the magnitude of the threat sea level rise poses to coastal infrastructure and communities in the long term. For this reason, it is important to embark on adaptation pathways that enable future flexibility. Adaptive design of engineering projects and buildings can help ensure they reliably function over their full lifetime—with the potential to be upgraded as needed—taking into account the plausible range of climate futures.

Communities will need to weigh their choices: for example, making a limited investment to protect an asset at risk in the near term, and then using the time gained to relocate the services it provides—or the community more broadly—to higher ground.

6: Cut heat-trapping emissions to limit the pace and magnitude of sea level rise

Sharply curtailing global heat-trapping emissions and phasing out fossil fuels while ramping up clean energy solutions must also be a cornerstone of our work to enable resilience on our coastlines. While near-term sea level rise is largely locked in, the choices nations make about reducing global emissions, starting right now, could lead to profoundly different levels of risk on our coastlines over the course of the century. As a relatively wealthy nation and the leading contributor to historical heat-trapping emissions, the United States has a unique responsibility to contribute to global climate efforts. Decisionmakers at local, state, federal, and international levels must prioritize a rapid and equitable transition to clean, affordable energy while ensuring a phaseout of fossil fuels.

For more information about coastal infrastructure at risk, you can view the report, use our interactive map to learn what vital assets are exposed to sea level rise in many coastal communities, and read our blog posts.