Four important global reports released in the last two days set up a deeply sobering context for the upcoming annual international climate talks in Egypt, also called COP27. These reports—from UN Climate Change, the UN Environment Program, the World Meteorological Organization, and the International Energy Agency—show that the current global trajectory of heat-trapping emissions is dangerously off-track, which potentially sets us up for catastrophic climate impacts.

There is still much we can do to bend that emissions curve sharply within this decade—but only if world leaders, especially leaders of richer countries and major emitting nations, take responsibility to act together quickly and fossil fuel companies are held accountable for their decades of obstruction and deception.

The UN NDC Synthesis report

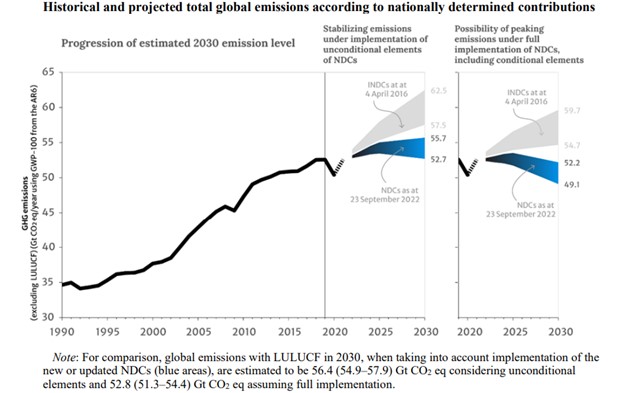

The 2022 UN NDC Synthesis report assesses the collective impact of emissions reduction pledges, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), that countries have submitted under the Paris Agreement. It shows a world dangerously off track and careening toward a temperature increase of around 2.5˚C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. While the overall emissions reductions are an improvement over last year’s assessment, because some countries have raised their NDCs in the interim, they are clearly far from sufficient.

A comparison of the current NDC trajectory with 1.5˚C and 2˚C-compatible trajectories from the latest IPCC report shows that we are far off from truly aligning climate action with what the science shows is necessary. Another way to look at this information is through the lens of carbon budgets—the remaining allowable amount of CO2 emissions that would still keep global average temperatures below a given level with a certain likelihood. Here too, the picture is bleak: with the current NDCs, by 2030 we will have nearly run out of the budget to have a 50 percent chance of keeping the temperature increase below 1.5˚C.

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report

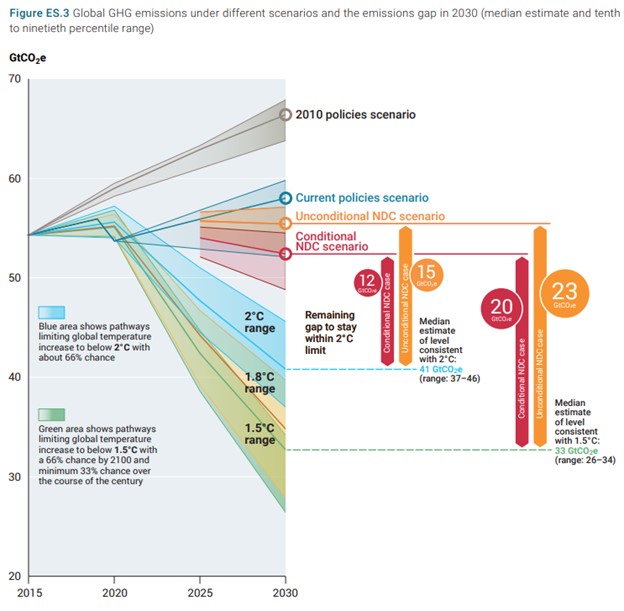

The UNEP 2022 emissions gap report is dire in its assessment of countries’ emission reduction commitments since last year’s COP in Glasgow, highlighting the continued large gap between these pledges and science-based targets for 2030 as well as the lack of credibility of many midcentury net-zero pledges. Under current policies, the report estimates the world is on track for a 2.8°C increase in global average temperatures by the end of the century. If NDCs are fully implemented, including all elements that are conditional based on whether climate finance from richer countries is forthcoming, that would go down to 2.4°C. (The Emissions Gap and NDC Synthesis report use slightly different assumptions, but the range of temperature estimates are very much aligned).

At this point, based on actions to date, the report finds “no credible pathway (to limit temperature increase) to 1.5°C in place” today. The only way to bridge this gap is through rapid, transformational changes across the global economy in every sector within this decade.

The World Meteorological Organization Greenhouse Gas Bulletin

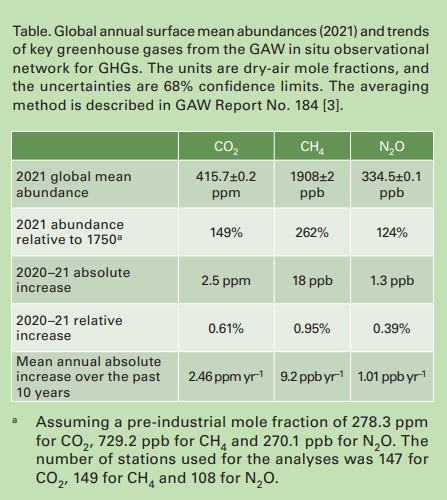

The WMO’s GHG bulletin’s headline takeaways are stark: Atmospheric concentrations of three major heat-trapping gases, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) hit all-time highs in 2021 (see table below). Methane emissions showed their biggest annual increase in 2020 and again in 2021. While scientists are still determining the exact reasons for the surge in methane emissions, the possibility of climate feedback loops whereby increased warming may be causing tropical wetlands to release methane cannot be ruled out. A truly scary prospect.

The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook

The IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook shows that, in 2021, global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels had a record-breaking annual rise from the previous year, a sharp rebound from the first year of the pandemic that was in part driven by a surge in coal use. High energy prices have caused a record transfer of wealth from consumers to producers, leading to a $2 trillion windfall for fossil fuel producers above their 2021 net income even as many millions have been thrust into energy poverty. At the same time, 2021 was also a year when renewable electricity generation reached a record high globally.

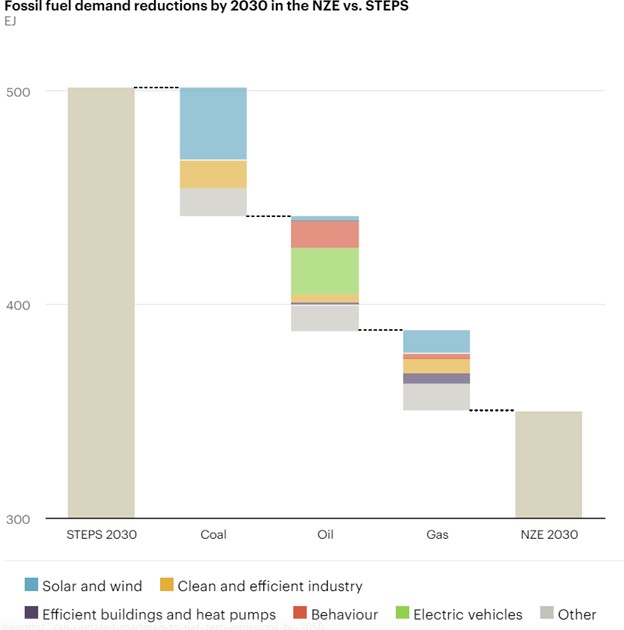

The report also provides important perspective on what it will take to bend the global emissions curve to align with climate goals, including in the current context of Russia’s unjust war in Ukraine and the global energy crisis that has unleashed. Getting to net zero emissions by 2050 from our current trajectory (which the IEA calls its Stated Energy Policies Scenario or STEPS) will take an unprecedented increase in investments in clean energy.

The key components to reach this goal are well known and reiterated by the IEA. They include: ramping up energy efficiency across all sectors of the economy; a dramatic increase in renewable electricity while phasing out fossil fuels, especially with wind and solar power displacing coal; a rapid expansion in electric vehicles and shifts in behavior that drive reductions in oil use; and electrification of buildings and industry. Under this scenario (which the IEA calls the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 or NZE scenario), renewables reach 60% of global electricity generation in 2030 and no new conventional coal plants are needed.

Energy investments, which accounted for just over 2% of global GDP annually between 2017 and 2021, rise to nearly 4% by 2030. According to the IEA, “From USD 1.3 trillion today, clean energy investment rises above USD 2 trillion by 2030 in the STEPS, but it would have to be above USD 4 trillion by the same date in the NZE Scenario.”

The IEA report is clear that this transformational shift in the energy system is both vital to meet climate goals—and must be handled with deliberate policy and funding support to avoid creating new vulnerabilities. Addressing energy poverty, incorporating climate resilience for energy infrastructure, building a modern and flexible energy system, fostering diverse, resilient clean energy supply chains and planning for a just transition must go hand-in-hand with decarbonizing the energy sector. Global cooperation is essential, including robust financial flows to help low- and middle-income countries switch to low-carbon energy.

Where to go from here?

The data are undeniably sobering, as is the lived reality of the climate crisis already here—but this also helps focus the mind and should provide the iron resolve to do more, do better. Steps we’ve taken in the last year—including passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and Europe’s REPowerEU plan—are moving us in the right direction, though not fast enough or far enough. The IEA and UNEP reports show that a narrow path still exists to limit the worst outcomes of the climate crisis, if we can marshal the political will to make the necessary clean energy investments quickly including providing sufficient climate finance for low-income countries.

With everything that hangs in the balance—our children’s future, our planet’s future—the choice is obvious. Will world leaders seize the opportunity to embrace it at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt? Can we break the stranglehold of fossil fuel companies over our energy and policy choices? Can we step back from the brink of a zero-sum game of incrementalism that will burn down the planet and instead deepen global cooperation to solve this collective challenge?

It’s easy to get cynical after decades of delay and inaction. Despair is a perfectly rational response too—I’ve been there. But I think we can only save ourselves if we guard against both—or, at least, hold space to also dare to imagine a future of transformative and just changes in our energy systems, our political systems, our economic systems, our social systems, and work as hard as we can to make that a reality. As I head to COP27 next week, that’s the vision of the world that I’ll be holding close.