In a world with rising seas and worsening storms, we’ve got to get smarter about how and where we build along our coasts. A new UCS report released today points out that our government-backed flood and wind insurance programs are encouraging risky coastal development that exposes coastal communities to harm and creates the potential for large damage costs paid for by all taxpayers. Local examples of policies that create risk are unfortunately common too: recently, New Jersey policy makers passed a bill that would allow development on piers in coastal high hazard areas, putting more people and property in harm’s way.

Rising seas and worsening storms threaten our coasts

This post is part of a series on

This post is part of a series on

A Summer of Extremes: Confronting the Realities of Climate Change

Subscribe to the series RSS feed.

Because of human-caused climate change, sea level is rising globally at an accelerating rate. Rising sea levels mean that coastal storm surges ride on elevated water levels, allowing water to reach higher and deeper inland.

The flooding experienced in the wake of Hurricane Sandy shows how damaging such storm surge can be, especially if a storm hits near high tide as Sandy did. The impacts are devastating for coastal communities: lost lives, destroyed homes, loss of critical infrastructure, and lingering pain and suffering.

With an above normal, and possibly very active, hurricane season predicted by NOAA for this summer, we need to do more to prepare.

New Jersey coastline hard hit by flooding from storm surge driven by Hurricane Sandy. Credit: Master Sgt. Mark C. Olsen/U.S. Air Force

Our current system of insurance is failing to help us manage our risks effectively

The UCS report, Overwhelming Risk: Rethinking Flood Insurance in a World of Rising Seas, highlights how the taxpayer-subsidized National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is riddled with perverse incentives that encourage risky coastal development. Artificially low premiums that don’t reflect true risk, flood-risk maps that don’t include sea level rise projections, inefficient subsidies, and the occurrence of major storms like Katrina, have led to a program that is already over $20 billion in debt. That number could reach nearly $30 billion once all the claims from Hurricane Sandy are settled. NFIP is virtually the sole provider of flood insurance for homes and small businesses, providing more than 5.6 million policies covering $1.25 trillion in insured assets nationwide.

Furthermore, growing coastal population and development, coupled with rising seas and worsening storms, mean that NFIP’s future solvency is even more threatened.

Coastal state-subsidized wind insurance programs are also at financial risk, especially as, in a warming world, North Atlantic-forming hurricanes are likely to be stronger and more destructive. Florida’s program has experienced a 150 percent increase in exposure to loss since 2005. Its insurance and reinsurance program have a combined total exposure of $2 trillion. If a major storm were to hit, the state of Florida may find itself unable to cover the damage costs.

Severe beach erosion threatens homes on Plum Island, MA in the wake of Winter Storm Nemo in February 2013. Credit: Mike Seidel.

Growing coastal risks are a liability for taxpayers nationwide

Coastal communities are on the front lines of dealing with harmful impacts when major storms hit. But a part of the costs of coastal flooding and storm damage are also spread to all taxpayers who help pay for insurance claims and for disaster relief.

Low NFIP insurance rates are taxpayer-subsidized and don’t reflect true risk. One industry study estimates that rates are one-half to one-third what they should be to reflect risk. In 2012 FEMA estimated that approximately 20 percent of its residential flood insurance policies were sold at subsidized rates, nearly all of which were located in high-risk flood areas. NFIP’s future solvency is also threatened by its growing debt, a legacy of major storms.

In addition to insurance subsidies and payouts, taxpayer-funded disaster relief costs can be large as well: the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013 provided for over $50 billion to help communities recover and rebuild after Sandy.

We urgently need to reform our insurance system

The new UCS report provides several commonsense recommendations for reforming the insurance system, including:

- Ensuring that insurance premiums reflect true risk

- Improving flood-risk maps so that they include sea level rise projections

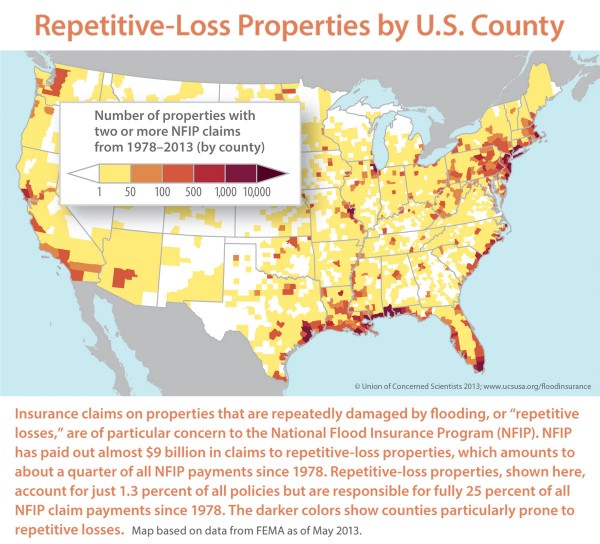

- Discouraging building and rebuilding in areas at high risk of flooding by phasing out all “grandfathered” low insurance rates and curtailing payments to properties that flood repeatedly

- Creating more options for at-risk communities through home buyout and relocation programs

- Communicating flood risks clearly and transparently to coastal communities

- Setting smart guidelines for climate-resilient rebuilding

The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 (H. R. 4348, Title II, Subtitle A) is taking some important steps to address shortcomings in the NFIP but we need to go further. Starting this year, the act will phase in increases in insurance rates to reflect risk and start to phase out subsidies for some properties. It also establishes a council that will advise FEMA on how to incorporate sea level rise and other coastal impacts in future flood risk maps. However, the process, timing, and resources required for these map updates are unclear.

The burden of coastal risks is unequal

Low-income communities are often among the hardest-hit by coastal storms. Recent studies show that Sandy had an especially severe impact on low-income communities and communities of color in New York and New Jersey, mirroring the aftermath of Katrina seven years earlier.

Instituting a program of vouchers, rebates, or other subsidies can help these property owners maintain adequate insurance coverage even as rates increase. Rebuilding and disaster relief efforts also need to be targeted to help meet their needs.

New Jersey’s bill is a case study in how NOT to manage coastal risks

Insurance is one tool to help manage risks along our coasts; we clearly need to do more to help communities assess their risks and make more resilient building and rebuilding choices. But the recently-passed New Jersey bill (S. 2680) goes in precisely the opposite direction. It would allow development on piers which are classified as the most at risk for coastal flooding and wind damage based on FEMA’s latest flood maps released earlier this year. Many of these areas are classified as V-zones by FEMA, and as such have a 26 percent chance of being flooded within the lifetime of a 30-year mortgage. (Atlantic City is currently the only high-risk place in New Jersey where this kind of development is allowed.)

To encourage building where FEMA maps indicate high risks (not just from flooding, but from the impact of waves, hurricane-force winds, and erosion) seems particularly short-sighted. FEMA’s flood-risk maps are by no means perfect – for example, they do not take into account projections of sea level rise so are an inadequate basis for long-term planning. But they do provide a threshold understanding of current risk.

New Jersey already faces significant risks from flooding because of its densely populated coastline’s exposure to Atlantic storms. It ranks third in the nation for total NFIP payouts since 1978 and has the fifth highest number of NFIP policies in the nation.

S. 2680 has been criticized by numerous organizations that work on reducing flood risks, including the New Jersey Association of Floodplain Managers and the Association of State Floodplain managers, which have both sent letters to Governor Christie urging him to veto the bill.

Coastal state policy makers need to step up

Governor Christie and other coastal state policy makers need to put the safety and welfare of their constituents ahead of narrow short-term economic interests. New Jersey’s future is not best served by increasing the vulnerability of its citizens, and their property, to extreme weather and coastal climate impacts, as S. 2680 would do. Governor Christie has an opportunity to cement his legacy as a leader who puts common sense and pragmatism above politics and special interests by vetoing this bad legislation.

Now is the time for policies and measures, including insurance reform and better coastal planning, that can help build long-term resilience to the very real and serious climate impacts coastal states are already experiencing. We also need to make deep cuts to our carbon pollution to slow the pace of warming and sea level rise that threaten to undermine our prosperity.