The people who pick our food, the people who rescue us when we endure an emergency, the people who build the homes that we live in—we are constantly benefiting from the efforts of the roughly 32 million people whose jobs require that they work outdoors in the US. They are essential, ensuring that many of us can stay fed, housed, and cared for, and at the same time, they are not guaranteed basic protections to ensure that they themselves can stay safe.

We know that climate change is taking heat to new extremes here in the US and abroad, so just how bad could this situation get? What could be at risk for outdoor workers if we don’t take action on climate change, and what could be gained if we did? In UCS’s new report “Too Hot to Work” (based on a study conducted with Prof. John Abatzoglou from the University of California, Merced), we sought to answer these questions and show why we need to be ramping down heat-trapping emissions and ramping up protective measures for outdoor workers across the country right now.

Our methodology in a nutshell

Using the results of our previous study, Killer Heat in the United States, we coupled county-level U.S. Census data on outdoor workers and their earnings with county-level projections of how the heat index, or “feels like” temperature, is likely to change this century under three different global warming scenarios. We used these numbers together with guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health (NIOSH) on how outdoor work schedules should be adjusted in the face of extreme heat.

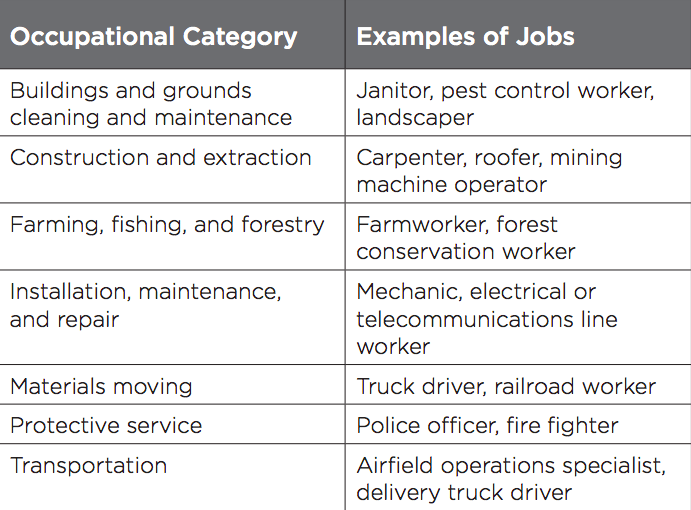

We calculated the number of workdays and earnings that could be at risk of being lost for outdoor workers at both mid- and late-century under three global warming scenarios, ranging from a “rapid action” scenario in which we limit warming to 2°C (3.6°F) above pre-industrial levels to a “no action” scenario in which emissions rise through to the end of the century. We did this for seven occupational categories.

The occupational categories included in “Too Hot to Work” and examples of jobs that fall within the categories.

We further looked at who would be at disproportionate risk of being harmed by extreme heat and potential income losses. In particular, we focused on outdoor workers who identify as Hispanic, Latino, Black, or African American as they account for more than 40 percent of outdoor jobs, yet they comprise approximately one-third of the general public.

We project staggering increases in unsafe workdays, especially without climate action

We found that by mid-century, without action on climate change, the staggering increases in extreme heat that we projected in Killer Heat would translate into staggering increases in unsafe workdays and potential earning losses. 18.4 million outdoor workers would risk losing a week or more of worktime on average each year. Outdoor workers across the country would face losing $55.4 billion in earnings annually.

And outdoor workers who identify as Hispanic, Latino, Black, or African American would be disproportionately impacted, with about $23.5 billion of total earnings at risk. Construction and extraction workers would have the most total earnings at risk ($14.4 billion), which is in part because they account for the largest portion of outdoor workers (nearly one quarter) and on average have higher income levels than the other occupations that we looked at.

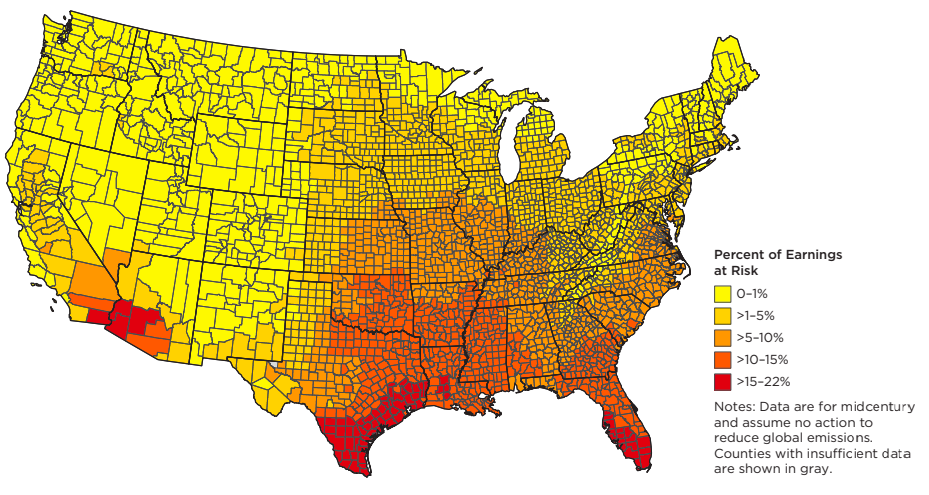

Percent of annual outdoor worker earnings at risk of being lost in each county of the contiguous United States at midcentury (2036-2065) with no action on climate change.

Of course, this wouldn’t manifest evenly across the country. For example, we found that in Louisiana, outdoor workers risk losing 34 workdays each year on average as a result of extreme heat—up from six days historically. This would put approximately $4,700 (~14 percent) of earnings at risk each year for the average outdoor worker in Louisiana. $4,700. In the next few decades.

You can dive into the results, and check out interactive maps, spreadsheets, and other resources that accompany the “Too Hot to Work” report on our website.

Outdoor workers lack mandatory protections from extreme heat, creating incredible cruelties

In light of the clear danger heat poses to outdoor workers, it is unconscionable that— at the federal level and in every state except Washington and California—there are no measures that employers are required to take in order to keep workers safe in the face of extreme heat.

In June of 2019, Procopio Magaña died in Florida after harvesting tomatoes for more than six hours in brutal heat conditions. According to the CDC, crop workers are 20 times more likely to die from heat-related causes compared with all other civilian occupations. Research has also found that Hispanic individuals are at particularly heightened risk of dying as a result of heat exposure on the job in part because they comprise a large portion of the outdoor workforce, and likely because of other factors including language barriers and a lack of access to quality healthcare. Similarly, non-U.S. citizens between the ages of 18 to 24 are 20 times more likely to die because of heat exposure than U.S. citizens.

In 2021 we should not have people dying on the job because of extreme heat exposure. These deaths, as well as heat-related illnesses and injuries, are preventable by affording outdoor workers simple measures such as adequate breaks, access to cool water and quality shade. We should not have outdoor workers put in the position of having to choose between their health and a paycheck.

We all depend on outdoor workers. We often deem them essential. It is time that we treat them as such.

We need guaranteed protections for all workers regardless of their immigration status. The U.S. Congress must pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act of 2021. This legislation is named after a farmworker in California who died after harvesting grapes for 10 hours straight in triple digit temperatures. It would require that the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) set an enforceable heat standard so that there are measures that employers must follow to keep outdoor workers safe in the face of extreme heat. It would prevent the death, exploitation and unnecessary suffering of workers who put food on our tables. It would, in summary, afford outdoor workers basic human rights.

To limit just how much extreme heat will increase across the United States, we need to take aggressive action on climate change now. We need to ramp down heat-trapping emissions by ending our use of fossil fuels – something that we are already seriously late to the table on. We need to expand the use of proven, low cost renewable energy resources—investments that can create jobs and career pathways for workers across the country. We need to electrify as many sectors as possible and modernize our public transit systems by, for example, expanding the availability of clean, electric buses and electric vehicle charging stations. The Biden Administration and Congress need to implement the climate commitments that have been made, and in manners that are fair and just for those communities who have been most affected.

This is a story about outdoor workers and it’s a story for all of us. Next time you sit down for a meal, think about the people who worked hard to produce your food. When you do, please take a moment to reach out to your members of Congress to urge them to pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act of 2021 and to pursue equitable measures to reduce our heat-trapping emissions. While you’re at it, ask your members of Congress to support the Preventing Health Emergencies And Temperature-related (HEAT) Illness and Deaths Act. That’s one of the best ways that we could give thanks.