It’s alarming to read headlines like: “EPA budget may be cut by 25% under Trump;” “DOE targeted for massive cuts in Trump draft budget;” “White House proposes steep cut to leading climate science agency;”and “Trump wants 37% cut to State, USAID.” But if you find yourself getting swept up in the hysteria, just remember that the president doesn’t rule by fiat; he’s president, not emperor.

There is certainly reason for concern about the vulnerability of specific federal programs and line items to spending cuts. People who care about science and research, public health, innovation and clean energy, international diplomacy, extreme weather and climate change need to be vigilant in articulating the importance of these priorities to their congressional delegations.

But the reality is that our system of checks and balances, as well as good ole’ fashioned local politics, will make enacting the president’s budget nearly impossible.

Running the gauntlet of congress is hard

The president only controls one of the three co-equal branches of government. He doesn’t make law and he doesn’t hold the purse strings; that’s congress. And congress can’t pass a spending bill to fund the government without bipartisan support; 60 votes are needed and that means the Republicans need at least 8 votes from the other side of the aisle.

Photo: Wikimedia

Reaching agreement on federal spending has always been challenging and congress is more divided now than ever. That’s why federal legislators have relied more and more in recent years on “continuing resolutions,” which keep the government going at the previous year’s spending levels.

More to the point, the kind of budget cuts the administration is proposing have the potential of uniting Democrats and Republicans in opposition, since they negatively impact both red and blue states indiscriminately. Fiscal conservatism, like talk, is cheap when it’s your own constituents threatened by proposed budget cuts.

Budget 101

How does the budget process work, in theory?

- The president releases his annual budget request, which typically happens in early February, kicking off the budget process. Current budget law says that it should be submitted between the first Monday in January and the first Monday in February, although it’s not uncommon for this process to be delayed when a president is serving in his first year.

- Congress then holds hearings on the budget, and the house and senate budget committees report out their own “non-binding” budget resolutions, which set the overall spending caps for the spending bills.

- Congress passes the budget resolution, usually in April, and that kicks off the appropriations process.

- The 12 Appropriations Subcommittees develop 12 separate annual bills that fund the government. Consideration of these bills begin in May and they are usually voted out of committee before the August recess.

- Congress then has until September 30th (the end of the fiscal year) to pass the 12 appropriations bills. Differences between the senate and house bills must either be reconciled in conference, or one of those bills must pass both chambers, prior to reaching the president’s desk and being signed into law, or the government effectively shuts down.

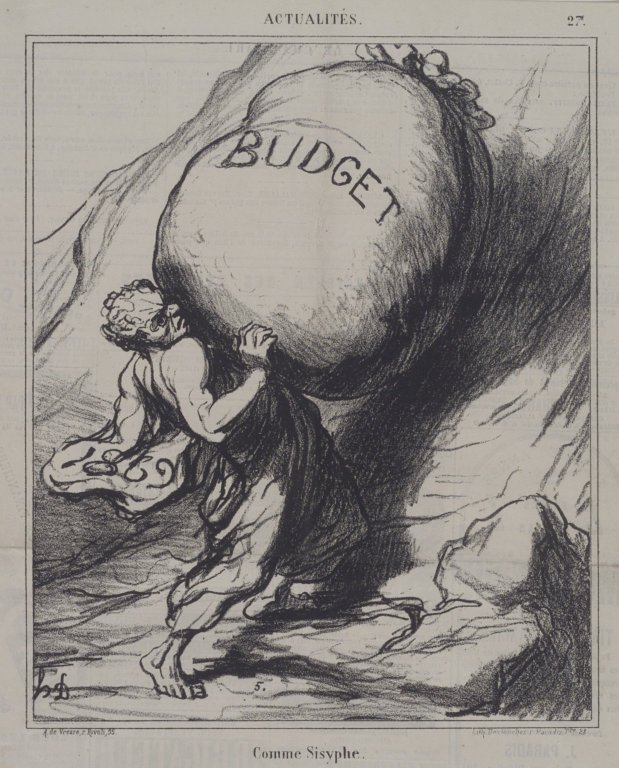

Photo: Wikiwand

Budget 102

This is 2017, though, and things are more likely to work like this:

Breaking from the tradition of a comprehensive budget request, President Trump is taking a piece-meal approach to the budget this year, the first piece of which is expected this week, focuses on defense and “discretionary spending.” We are likely to see a request for big increases in defense spending, paid for with steep cuts to other agency spending, like what we’ve been reading in the headlines. Additional pieces of his budget focused on “mandatory spending,” including big programs like Medicare and Social Security, are expected in April.

Congress doesn’t always pass a budget resolution, especially when one chamber is controlled by Republicans and the other is controlled by Democrats. But even with their own party currently in control of both the house and senate, the administration may have a hard time garnering the support of some Republican budget committee members, who have already publicly expressed opposition to draconian spending cuts at some agencies. If congress does pass a budget, it will likely contain very different spending levels from the president’s budget.

All indications are that the budget committees will move forward without the president, their only guidance being the fiscal year 2018 (fy18) sequestration caps in the 2011 Budget Control Act, which they will probably try to get rid of so they can increase military spending.

Appropriators in both chambers have indicated a desire to pass a spending package that avoids a government shutdown before April 28th, when the continuing resolution passed last year for fy17 expires. But big differences between the house and senate make it just as likely that congress has to pass another continuing resolution to keep the government operating at level spending for the rest of fy17.

Appropriators will develop their fy18 bills and move them out of committee (in most cases along party lines), but controversial amendments, known as “riders,” and the 60 vote filibuster, all but assure that many of those 12 funding bills won’t pass the senate. Even in the Republican-controlled house where only a simple majority is needed to pass legislation, the “Freedom Caucus,” consisting of conservative Republican members who advocate for smaller government, has sometimes made it hard for Republican spending bills to move forward without receiving Democratic support.

Congress hasn’t made the September 30th deadline in over 20 years, so they’ll probably need to pass another continuing resolution to keep the government operating when the regular appropriations process again falls short.

And at some point, this will likely come down to a showdown where Republicans can’t pass a bill that is acceptable to both their right-wing base in the house and senate Democrats, who will hold tight in opposition to a budget that doesn’t reflect their interests. Reaching agreement is going to be extremely difficult, and I can already see the blame game over the government shutdown. Will the country blame the Democrats or the Republicans? Personally I think they’re likely to blame the party in control.

Cutting federal spending impacts red states

Photo: Wikimedia

If the president wants to gut National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite programs, he’s going to have to convince Senator Richard Shelby (R-AL), the Chair of the Appropriations Subcommittee of jurisdiction, that his constituents in Mobile and along their coast won’t be harmed by reduced capacity to forecast hurricanes and plan for extreme weather that floods communities, destroys homes and ruins livelihoods. He’s also going to have to convince subcommittee members and coastal senators Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Susan Collins (R-ME), and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) of the same thing. These senators are also likely to have concerns over impacts these cuts would have on fishing commerce, which is a big industry in all of these states.

Photo: Wikimedia

If the president wants to gut Department of Energy (DOE) programs, he’s going to have to convince Lamar Alexander (R-TN), the Chair of the Energy & Water Appropriations Subcommittee, that his constituents at Oak Ridge National Laboratory won’t be impacted; which will be a tough argument to make, since a diverse and large amount of DOE’s work is carried out at the national laboratories. The Chair of the House Energy & Water Appropriations Subcommittee, Mike Simpson (R-ID), will also be looking out for his constituents at Idaho National Laboratory. Less funding means less work, which means fewer jobs, which means unhappy constituents in those states. Not to mention, both Chairmen, and many others, have articulated a vision of the absolute necessity of the science and energy innovation work spearheaded by DOE.

What can ordinary citizens do?

The president can’t get 60 votes for anywhere near the kind of budget cuts he’s proposing. But if the American people aren’t speaking up loudly in opposition and raising concerns with their members of congress, the likelihood of cuts to essential areas of science, research, innovation, and programs that protect public health and the environment increases significantly. What can ordinary citizens do?

Photo: Wikihow

Call, write and meet with your members of congress and/or their staff, and tell them that:

- The earth sciences budget in NOAA and NASA is important because things like weather forecasting and scientific research save lives and help your state better understand and deal with the impacts of a changing ecosystem.

- The important work of DOE’s Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) program saves consumers money, grows new markets, technologies and businesses, and creates jobs in your state by advancing science and clean energy innovation.

- FEMA’s flood programs are vital to help protect your community and property from inland flooding or coastal flooding from storm surge and sea level rise.

- EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice helps protect children, the elderly, and economically vulnerable communities in your state from toxic pollution; the same communities that are most likely to be impacted from polluting industries.

These are the things congress needs to hear, and they need to hear them from constituents, to be empowered to stand firm in opposition to the Trump administration’s budget proposal. As long as the public stays engaged, the president is going to find out very quickly that if you don’t have a plan to work with congress—including Democrats—you’re not going to be able to advance your domestic agenda.

So what’s the administration’s plan? That remains to be seen.