In February 2022, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a bold statement. The United States, he said, should abandon its traditional policy of strategic ambiguity towards Taiwan, and commit publicly to defending it in case of military action by China to regain control of the island.

Ambiguity has been the defacto US policy regarding the defense of the government of Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan since 1979, when US President Jimmy Carter severed diplomatic relations with the ROC as a condition for establishing diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which it subsequently recognized as the sole legitimate government of all of China. That change was accompanied by the unilateral US passage of the Taiwan Relations Act, which was intended to ensure ROC-US ties remained everything short of an official diplomatic relationship. The act does not commit the United States government to defend Taiwan, but allows for military aid to the ROC government it can use to maintain a military capacity to defend itself. The act also preserves US legal, commercial, and cultural ties with the people of Taiwan.

A Taiwan contingency, Abe said, is a Japan contingency, reiterating a phrase he first coined in 2006. But what Abe did not say, and what current Japanese and US leaders do not seem to recognize, is that a dramatic change to the longstanding US and Japanese policy of ambiguity regarding the defense of Taiwan could lead PRC leaders to believe using military force to retake the island is their only option. They downplay the possibility that if PRC leaders were to act on that belief, Abe’s recommendation, echoed by influential US voices, would lead to the outbreak of a major war between two nuclear-armed militaries where Japan becomes a battlefield.

The US, Japanese, PRC and ROC governments all want to avoid a war that no one is likely to “win.” The costs for all four, whatever the eventual outcome, are simply too high. Unnecessary provocations, like the one Abe suggested, will not make the region any safer, but dialogue might. The first step toward lowering tensions and reducing the risk of war is to build a new East Asian diplomacy that takes all stakeholders’ concerns into account, a diplomacy that reflects the concerns of the people who live in East Asia.

What does the public want?

Should the Japanese government allow US military bases or the Japanese Self-Defense Forces to be used in a US war with China over Taiwan? To some, the use of US bases in Japan in such a conflict is an indispensable prerequisite for United States military participation. Early this year, after war-gaming a conflict over Taiwan, the Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS) listed Japanese support as essential to a successful defense.

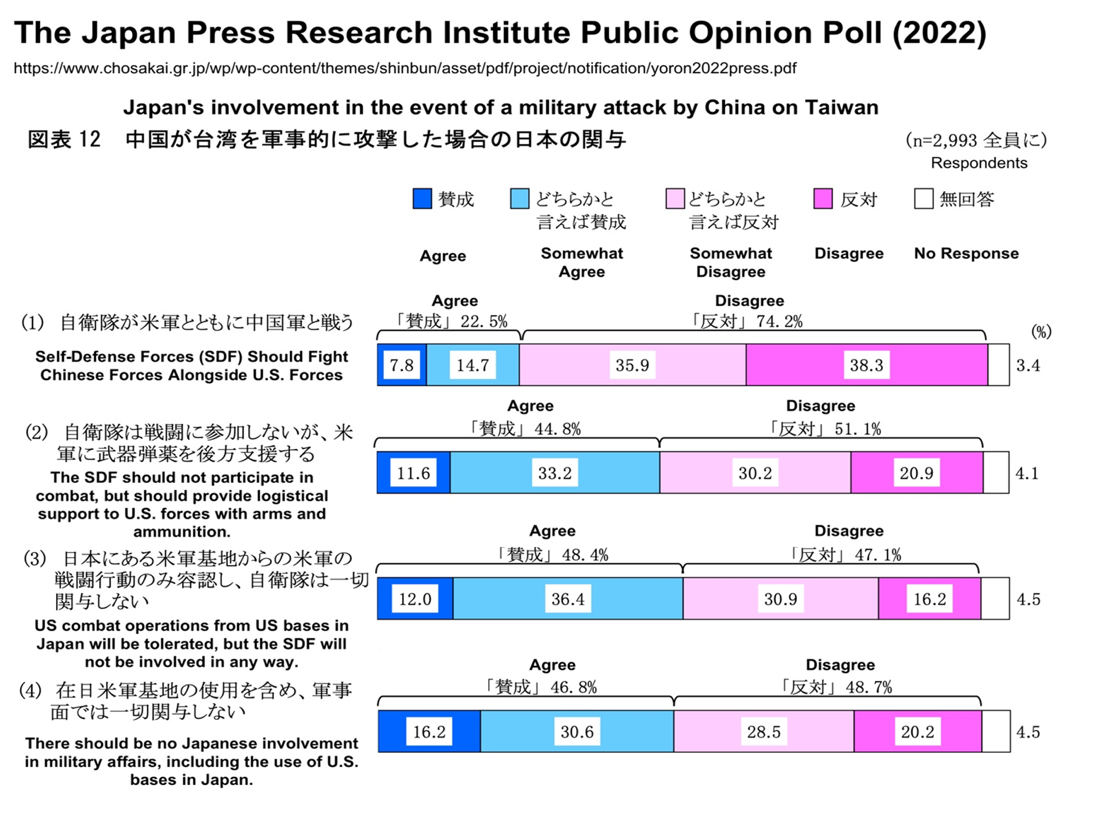

While Article 6 of the US-Japan Security Treaty allows the United States to use its Japanese bases to maintain “international peace and security in the Far East”, prior consultation with Japan on any military operation is required. Some Japanese leaders, like Taro Aso, are urging the Japanese public to show a clear determination to fight in a US-China war. And perhaps that message plays well in Taiwan, where 60% of respondents said they found it likely that Japan would send its Self-Defense Forces to defend Taiwan. But the Japanese public is divided on the question of allowing the use of US military bases in Japan and strongly opposed to allowing Japanese forces to fight in a Taiwan contingency. In a recent poll (shown below), 47.1% say the Japanese government should not allow US combat operations from US Japanese bases in the event of a war with China over Taiwan. Heightened public concern about this possibility led to questions in the Diet. In early 2023, Prime Minister Kishida was asked, on two separate occasions, if there would be prior consultation and whether Japan could say no to a US request. Kishida answered that the Japanese government could refuse, although most experts consider that unlikely.

Japan Press Research Institute Public Opinion Poll (2022).

In the same poll, 74.2% of Japanese citizens disagreed with the assertion that the Japanese Self Defense Force should fight alongside US troops.

People in Taiwan and the United States share the same concerns. Recent polling in Taiwan shows that a historically high 60% of Taiwanese people prefer to maintain the status quo in the island’s relationship with the PRC. In the United States, recent polling indicates that 73% of respondents favor prioritizing high-level US-China diplomatic talks aimed at avoiding war.

These polls were taken in the context of increasingly frequent, highly speculative, poorly documented analysis of Beijing’s goals for Taiwan. Several US admirals and generals have predicted a military conflict in the next 5-10 years. But even if Beijing refuses to take force off the table, there is little indication that an invasion is coming soon, in large part because they, too, understand the extreme costs of a war. Aside from the costs to human life and risks of high-level escalation, the Chinese economy, and society as a whole, would be highly vulnerable to a cut-off of foreign trade.

Anxieties and tension

During and after the late Abe’s leadership, Japan responded to China’s growing regional presence and strength by seeking greater security assurances from the United States. Its self-enforced pacifism post-World War II is eroding in the face of a perceived increase in regional tension.

There is a small but influential group of Japanese and US officials that have long wished for stronger bilateral security ties and for Japan to take a greater role in this collective security arrangement. Abe himself has long been a proponent of Japan fully rearming itself. After the institutionalization of South Korean-Japanese-US trilateral security ties and Japan’s decision to raise its defense budget to 2% of GDP, an East Asian security bloc designed to counter China is emerging.

Abe also floated the possibility of the return of nuclear sharing, meaning the United States re-deploying nuclear weapons in Japan, for the first time since 1972. This would violate Japan’s “non-nuclear principles”, which prohibit Japan from manufacturing, possessing or hosting nuclear weapons, and would thus be a significant change in policy.

Abe’s goal in bringing up nuclear sharing was not to express outright support for its return, but to “start a discussion.” Japan’s current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, while voicing opposition to Japan hosting nuclear weapons, concurred that discussion was fine; the public expressed a similar opposition to the policy but not to the discussion.

On the US side, the recently released Strategic Posture Review, a congressional response to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, also calls for US theater nuclear forces to be deployed in East Asia. Reintroducing US nuclear weapons would significantly increase the risk of nuclear war, either by accident or design. Moreover, China has become increasingly concerned about US emphasis on low-yield nuclear weapons, especially when combined with the intentional US ambiguity on the possibility of US first-use. Stationing nuclear weapons in Japan would undoubtedly raise those anxieties even further. And it would certainly lead to a much more nervous and aggressive North Korea.

Diplomacy as defense policy

Aggressive rhetoric, new nuclear weapons policies and high-level congressional visits to Taiwan all contribute to putting people’s lives, first and foremost Taiwanese lives, at risk. The Japanese steps towards remilitarization stem from concerns that can be better assuaged by diplomacy.

Civil society can play a constructive role in building a framework for dialogue. In October of 2023, the Union of Concerned Scientists partnered with New Diplomacy Initiative from Japan and Korea’s Korea Diplomacy Plaza to organize the first East Asian Quadrilateral Dialogue between the United States, China, Japan and the Republic of Korea. Our goal is to use this forum to explore new ideas and set an example for our governments on how dialogue, diplomacy and cooperation can make the region more stable, peaceful and prosperous than increased military posturing, procurements and deployments.

The meeting between President Xi and President Biden on the sidelines of the APEC Summit in San Francisco in November was a positive first step toward more bilateral cooperation on key issues and on securing guardrails for the relationship. But in the long-term, guardrails and increasingly aggressive nuclear posturing are no substitute for a meaningful security framework that makes everyone in the United States and East Asia safer.