Last November, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) released an interdisciplinary study exploring the various pathways to meeting US goals to cut heat-trapping emissions economywide 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions no later than 2050. The good news? It’s doable—and the United States would reap significant health and economic benefits in the process. The simple fact is that ditching fossil fuels for low-cost clean energy resources is good for the planet, good for the US economy, and good for public health.

But achieving this goal will have its challenges. It will take an unprecedented level of coordinated investment across all sectors of the economy. There are a lot of moving pieces, but it starts with decarbonizing the electricity sector and powering the economy with a diverse combination of clean energy resources—primarily wind, solar, and battery storage—connected with a modernized bulk transmission system that can reliably deliver electricity to consumers all 8,760 hours of the year.

How are we doing on that? Well, there’s progress to applaud, foot-dragging and setbacks to lament, and some real challenges yet to overcome. Let’s dig into it a bit.

Investing in transmission infrastructure is key

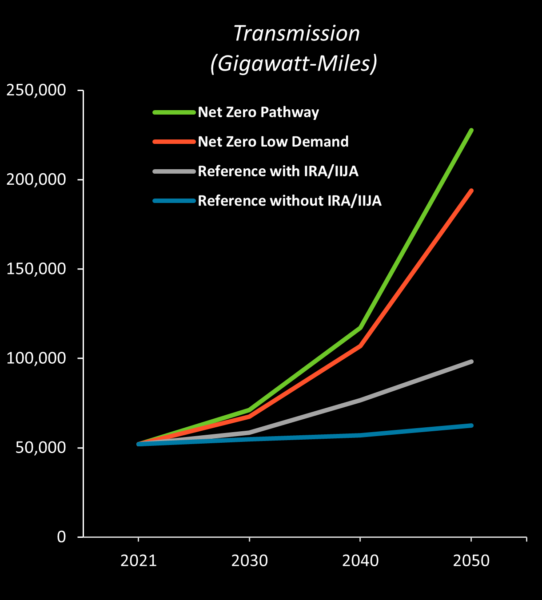

UCS’s November study, Accelerating Clean Energy Ambition, analyzed four core scenarios, including two net-zero scenarios for decarbonizing the economy by 2050, and two reference cases with and without the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure and Jobs Act. The net-zero pathway uses the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) projected demand for energy services, while the net-zero, low-demand scenario adds in feasible reductions in energy demand beyond what energy efficiency measures and technological changes alone could achieve. Under both net-zero scenarios, the transmission system needs to expand significantly to meet the increase in demand from electrifying other sectors, integrate high levels of wind and solar, and deliver that power to consumers.

UCS’s findings are consistent with the conclusions of the Department of Energy’s (DOE) National Transmission Needs Study, which it released last October. The agency’s meta-analysis looked at more than 100 transmission studies published since 2015 and found that under high renewable-energy and high demand-growth scenarios—representing the transition to clean energy as various sectors of the economy are electrified—the need for regional transmission would more than double and for interregional transmission more than quadruple.

The studies the DOE reviewed also found that transmission investments would provide a host of benefits beyond access to clean energy. Better reliability, improved public health, greater resilience to extreme weather, strengthened national security, expanded economic development, and lower energy costs as more people access renewable energy resources are among the many benefits that aggressive, smart grid investments would deliver.

Despite the recognized need for investment, progress is slow

I wrote a blog last June that detailed many of the initiatives underway to ramp up transmission system investments. Federal funding—a result of the IRA and the infrastructure act—has spurred transmission system investments in the West, Midwest, and Northeast that will help to cost-effectively deliver clean energy to millions of people. This is real progress, but federal funding for transmission system upgrades represents only a small fraction of the investment needed to meet US decarbonizing goals.

Other federal initiatives are progressing to accelerate permitting for federal land transmission projects and establish a more robust process for greenlighting investments that are not on federal land but have been determined by the DOE to be “in the national interest” by significantly benefiting consumers, but it is unclear what these efforts might accomplish. Limiting our transmission build out to federal lands won’t get us where we need to be, particularly given the environmental and cultural significance of some of these areas. Perhaps the biggest question, however, is how aggressive the DOE and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) will be in identifying national interest electric transmission corridors that aren’t on federal land and using new federal authority to permit transmission projects over state objections.

While the infrastructure act expanded DOE and FERC’s authority to approve and permit projects where transmission system investments are deemed in the national interest, it remains to be seen how willing the two agencies will be to step into an area that historically has been the domain of state authority. It’s a contentious issue fraught with political and social dynamics that have largely doomed previous attempts. The simple fact that the government refers to FERC’s permitting authority as a “backstop” means that we shouldn’t look to FERC to meet our expectations for transmission investments to enable a clean energy future.

FERC’s failure means uncertainty and delay

Probably more important than FERC’s backstop siting authority is its authority to regulate how regional grid operators plan, approve, and ultimately fund new transmission projects to meet the system’s future needs. To date, system planning has been piecemeal at best, with very little forward-looking system planning done across large regions of the country, most notably in the Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and New England. This has resulted in an antiquated transmission system that is unable to accommodate a transition to clean energy, meet growing electricity demand, or withstand climate change-fueled extreme weather and increasingly sophisticated cyberthreats. To be blunt: The United States is trying to power a 21st century economy and withstand 21st century challenges with a 20th century electricity grid.

To address this looming problem, FERC issued a draft rule in April 2022 that would require a much more forward-looking, comprehensive approach to transmission system planning. After issuing the draft rule almost two years ago, however, the agency has failed to move the ball. The rulemaking continues to languish despite requests from a variety of stakeholders to get the final rule over the finish line.

Real progress in some regions, less so in others

Back at the grid operator level, there is real progress in some regions, particularly in the Mid-Continent Independent System Operator’s (MISO) territory, which spans much of the Midwest down to the Mississippi Delta. In response to a rapid transition to clean energy happening across much of the Midwest, MISO has had its long-range transmission planning process in place for several years now. As a result, MISO approved its first portfolio of long-range projects in July 2022 and is working on a second portfolio of projects expected to be approved later this year. MISO currently has plans for two more rounds of long-range transmission planning over the coming years that will focus on its southern region and attempt to do a better job integrating its northern and southern regions.

There has been mostly talk—and not enough action—in other parts of the country. The Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland Interconnection (PJM), which operates the grid across much of the Mid-Atlantic, has been making some effort to get better system planning processes off the ground since the spring of last year, but it continues to struggle. Independent System Operator New England (ISO-NE), meanwhile, has conducted some long-term transmission studies, but it’s unclear how they will feed into a process that provides needed investments. Both PJM and ISO-NE also suffer from lingering uncertainty about FERC’s transmission planning rule that has the potential to send them back to square one if the agency finalizes it when they are in the middle of their ongoing efforts.

Despite progress, we’re still way behind

To sum it up, the country has made tangible progress over the past five years, but it is still woefully behind in building the transmission system that will not only meet US clean energy ambitions, but also deliver a more reliable, more resilient, and more equitable energy system. To get there will require holistic, forward-looking system planning to ensure grid investments are cost-effective, well-designed, and capable of meeting 21st century needs. And we need transparent and inclusive decisionmaking processes to make sure everyone benefits from a clean energy future. We’re not there yet, but it’s critical that we keep working at it until we are.