Let’s start this one with some good news: the transition toward clean freight is picking up speed. Over the past few years, we’ve started to see more and more zero-emission commercial trucks, delivery vans, and buses hit the road. The much-needed evolution of our on-road freight system to one that’s cleaner and more equitable is gaining momentum – and not a moment too soon.

Medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs), like the big rigs on our highways and the vans that deliver our packages, make up just over 1 in 10 of the vehicles on our roads, but are responsible for over half of ozone-forming nitrogen oxide pollution and lung-damaging fine particulate pollution from on-road vehicles. They are also disproportionately responsible for climate-warming emissions, representing around 30 percent of greenhouse gas pollution from vehicles on our roads and highways. Zero-emission trucks and buses eliminate tailpipe emissions and significantly reduce life-cycle pollution.

One indicator of this progress is the growing share of zero-emission truck and bus registrations. This tells us which fleets are deploying electric vehicles, which types of these vehicles are being deployed, and where. Information like this is vital to understanding how the market is developing, but I think it’s equally important to investigate the why as well – this way, we can better understand what’s working and what’s not. After all, these trucks aren’t going to electrify themselves (although this does kind of sound like a superhero blockbuster plot). Such a paradigm shift within our nation’s $400 billion on-road freight industry demands both regulatory forces and economic upsides to be successful and lasting.

Smaller vehicles and big fleets are leading the charge

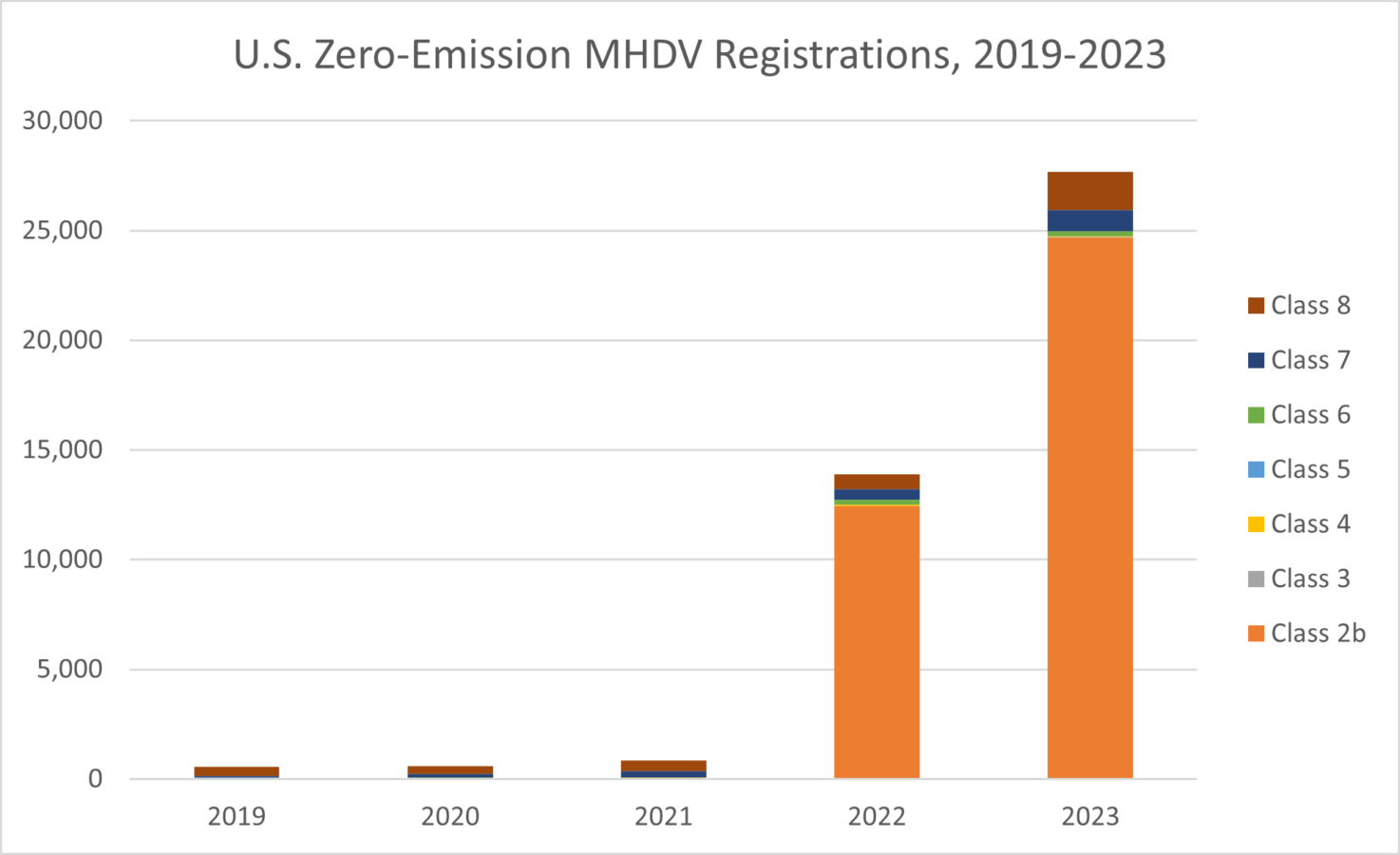

Where just a handful of zero-emission trucks and buses were deployed annually in the US just a few years ago (around 600 total in 2019), over 27,500 zero-emission MHDVs were deployed in 2023. While this represents a small fraction of the national MHDV sales (around 2.5 percent in 2023), the growth is impressive. What’s more, zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) uptake among certain sectors of the MHDV fleet has been nothing shy of meteoric in some states.

Cargo vans (the delivery vans that bring packages the last mile to your door) have seen the largest growth in ZEVs among all other MHDV types. In 2021, just a handful of zero-emission cargo vans were in operation nationally, however, today there are over 22,000 of these clean-operating vehicles making deliveries in our neighborhoods across the country. In 2023, electric cargo vans represented over seven percent of new registrations nationally for this vehicle type.

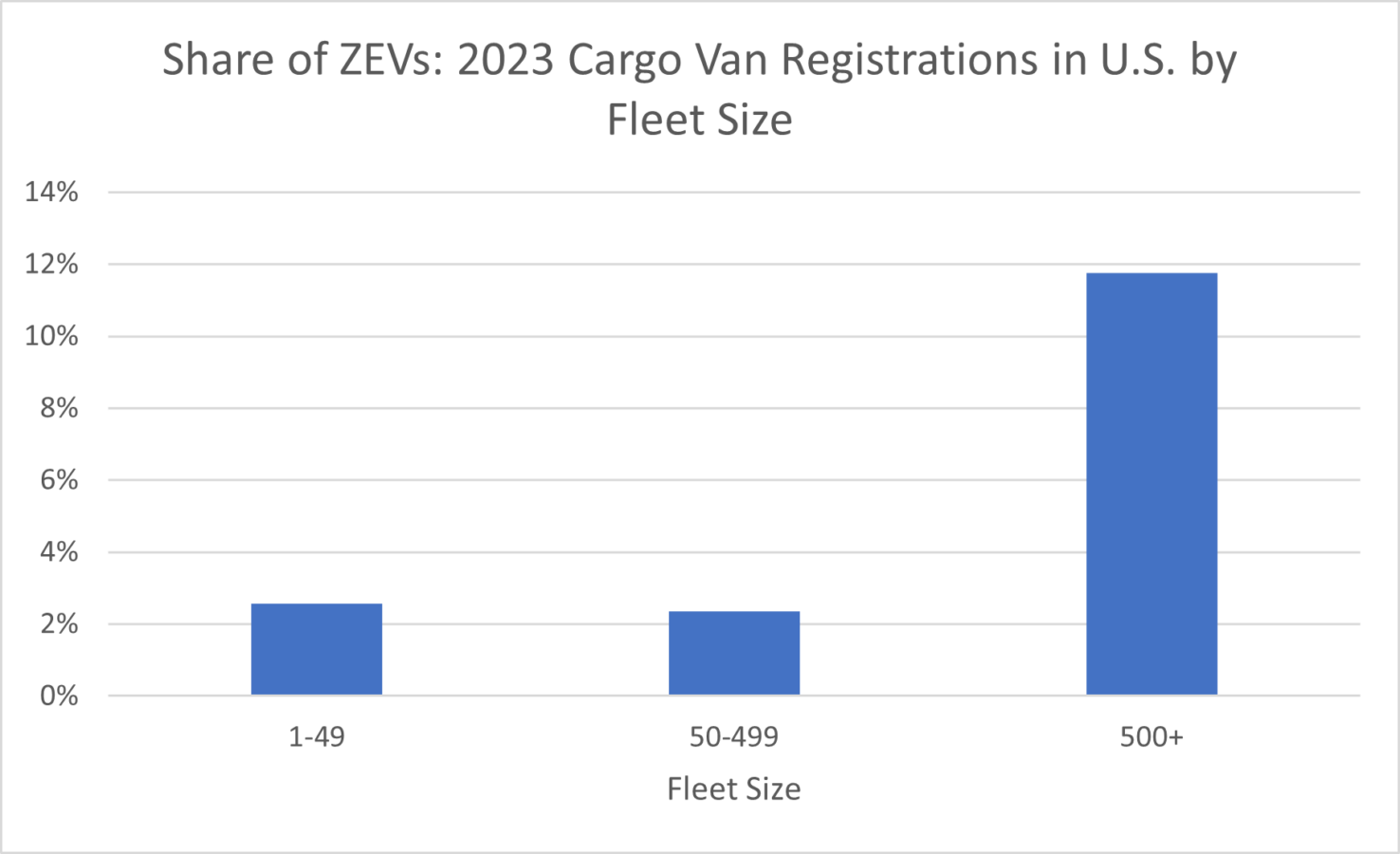

Large companies are leading this early growth. Around 12 percent of cargo vans registered by businesses operating over 500 vehicles were electric in 2023, compared to 2.58 percent by fleets with less than 50 vehicles and 2.35 percent by fleets with between 50 and 499 vehicles. This could be explained by larger companies having more access to capital to invest in zero-emission vehicles compared to smaller fleets, larger fuel bills that zero-emission trucks could help reduce, and more flexibility with larger numbers of vehicles. However, businesses of all sizes can benefit from the significant fuel and maintenance savings that electric vehicles deliver and the relative price parity between electric and combustion cargo and delivery vans makes these vehicles more approachable for businesses with less capital.

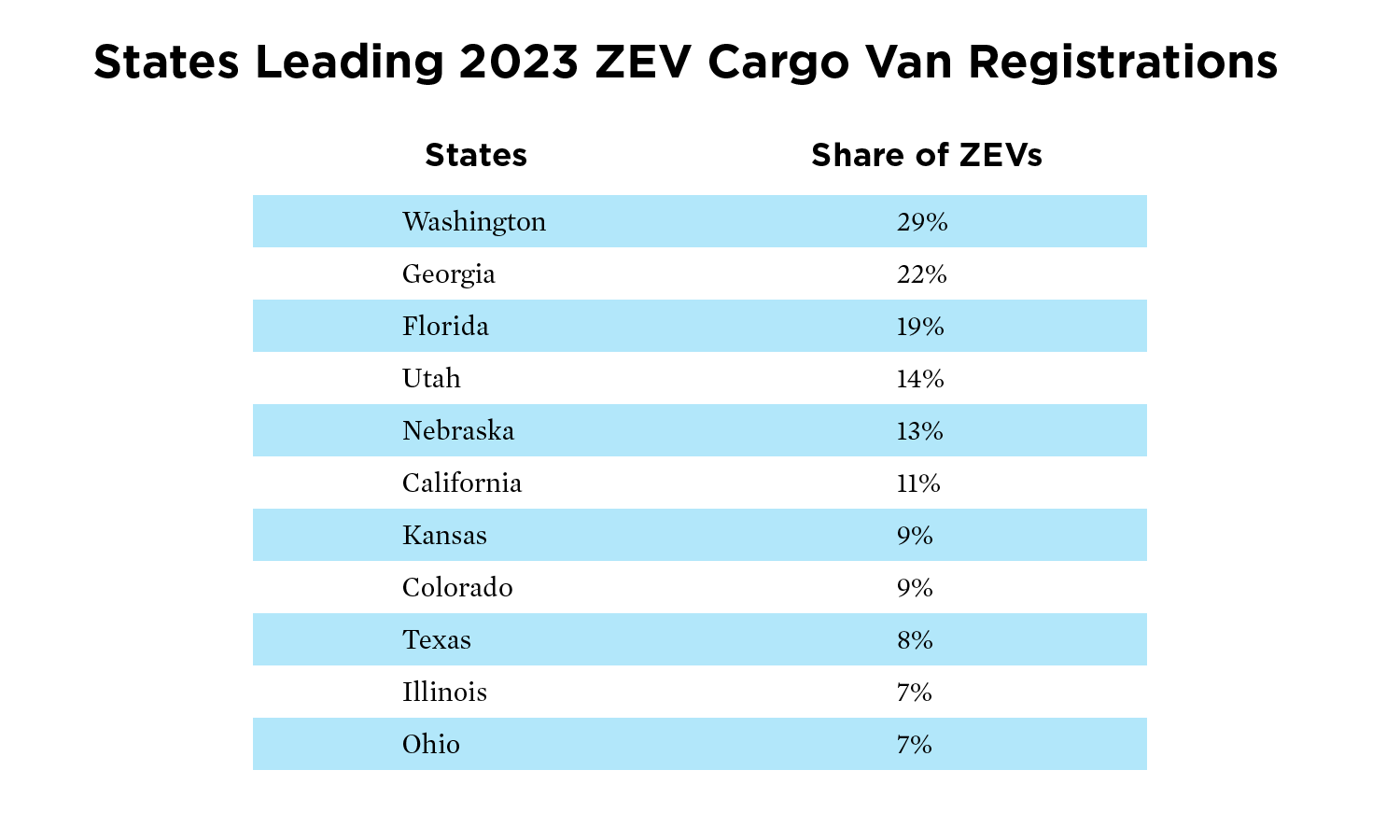

Some states are seeing more accelerated deployments than others. In 2023, nearly one in three cargo vans registered in Washington state were ZEVs. Georgia also stood out with over 22 percent ZEV registrations among cargo vans in 2023 – a good comeback mark for a state that was once a leader in electric passenger vehicle adoption. Interestingly, Florida registered the most electric cargo vans last year, around 3,400, representing just under 20 percent of all registrations for that vehicle type.

Several key reasons are behind this accelerated adoption.

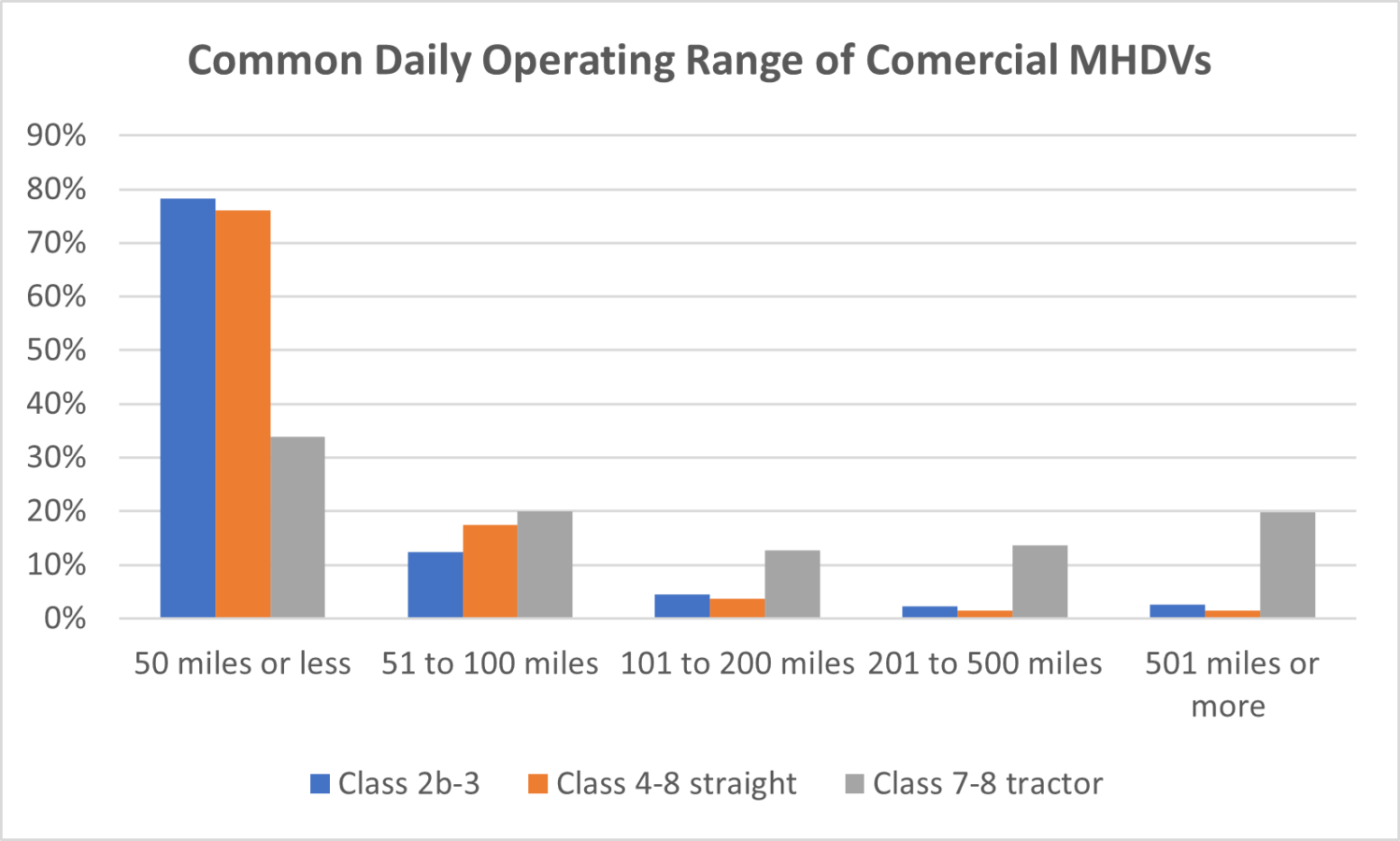

Electrification makes clear sense in the last-mile delivery sector (the last leg of an item’s journey). According to recent data from a Census Bureau survey of Class 2b and larger vehicles, over 90 percent of Class 2b and 3 trucks and vans travel less than 100 miles per day. Given that the range of the most common electric cargo vans on the market falls around 150 miles, fleets could see this is a no-brainer. Furthermore, delivery vehicles most often operate on predictable or fixed routes and return to a depot after the workday where electric vehicles could easily charge overnight and be ready for work the next day.

As mentioned earlier, another major factor is lower operating costs. Compared to a combustion model, electric cargo vans have significantly reduced operating costs in most cases. Using the current national average for electricity and gasoline prices, fuel costs for the electric version of Ford’s Transit cargo van are around $0.10/mile, while the gasoline-powered version costs around $0.19/mile. In many cases, electric cargo vans have reached upfront cost parity with analogous combustion models. Ford’s 2024 electric and combustion Transit cargo van models are virtually the same base price – just over $50,000. This price parity is in part thanks to the $7,500 federal tax credit offered under the Inflation Reduction Act, but it could be eligible for additional incentives, depending on the location. In California, for example, electric cargo vans are eligible for an additional $7,500 incentive from the state. Incentives aside, the upfront prices of electric trucks and buses are anticipated to decline.

A third reason we see such rapid adoption of electric delivery vans may lie in their depots. Costs related to building out charging infrastructure can represent a significant cost of fleet electrification. However, where larger trucks and buses often require high-power chargers, fleets of last-mile delivery vehicles can reliably charge overnight on the Level-2 chargers often seen in people’s garages. This significantly reduces costs associated with charging hardware and construction and reduces potential hurdles of local grid capacity and permitting.

While the national public health, environmental, and climate impacts from a delivery van pale in comparison to the larger, mostly diesel-powered trucks and buses, their impact is not insignificant – the Census Bureau reports that Class 2b and 3 vans in the U.S. travel over 33 billion miles annually (roughly the distance of 20 round trips from Earth to Saturn). The climate impact of these vehicles is similar to that of nearly 70 natural gas power plants operating for a year (26.02 million metric tons CO2e annually). Additionally, electric delivery and cargo vans will serve as an example of the potential for successful accelerated electrification among other sectors in our freight system. Fleets operating larger vehicle types running similar routes have a path paved by electric cargo vans.

There’s no way around it – this growth is impressive. What’s more, delivery vehicles are nearly ubiquitous in our neighborhoods across the country and could also help to generate greater interest in electric vehicles among the public.

In the coming months, UCS plans to follow up its landmark 2019 report, Ready for Work, publishing additional research and analysis on early truck and bus electrification successes, opportunities, and barriers – stay tuned!