In Massachusetts, communities of color are exposed to about 30 percent more fine particulate matter from transportation than predominantly white communities. At the same time, these communities also face socioeconomic challenges, including limited or no access to a working transportation system. This reality— that many people who are overburdened by transportation-related air pollution are also underserved by the transportation system itself— is an issue that mirrors widespread environmental injustices experienced across the country.

With the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, several New England and Mid-Atlantic states are collaborating as part of the Transportation and Climate Initiative Program (TCI-P). Officially announced in December 2020, the TCI-P will use a cap-and-invest model to raise funds through fuel allowances to invest in clean transportation improvements throughout the region. While the TCI-P promises encouraging public health and climate outcomes broadly, an October 2020 study from Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that the current policy will not fully reduce the air pollution disparities experienced by overburdened and underserved communities.

Policymakers from across the region see potential in the TCI-P to begin to address historic inequities in environmental, public health, and transportation justice. Advocacy groups have pushed to reinforce the program with strong protections and commitments for overburdened and underserved communities. The states in the TCI-P have officially committed to at least 35% of proceeds going to clean transportation projects in overburdened and underserved communities. But to do so, a critical yet challenging early step is to define and identify exactly what “overburdened and underserved” means in each jurisdiction.

The MassROUTES screening tool

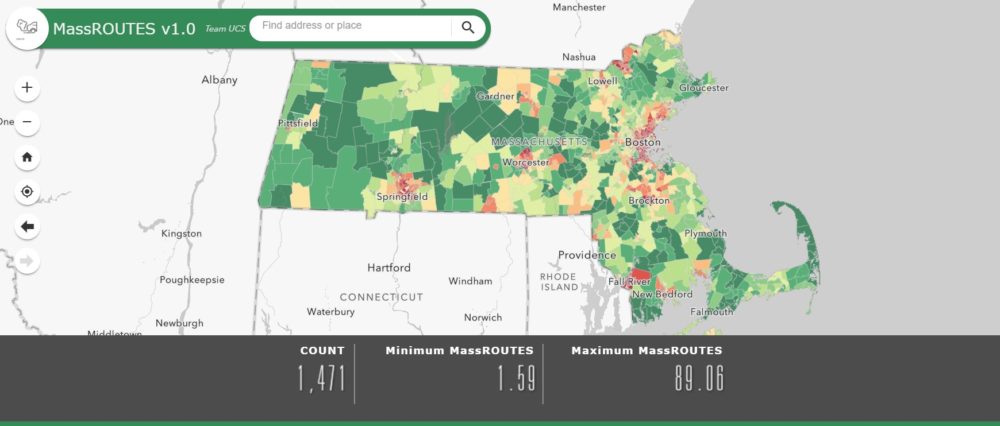

In early 2020, our team partnered with UCS to develop a screening tool that could help Massachusetts determine where the priority communities described above are located. We designed a GIS-based tool called Massachusetts Screening System to Recognize those who are Overburdened and Underserved by Transportation, Environment, and Socioeconomic status (MassROUTES). MassROUTES uses a set of indicators grouped in three categories— Environment, Population, and Transportation— to calculate an overall score for each census tract in Massachusetts. Examples of indicators include proximity to transit hubs and health care facilities, prevalence of asthma and COPD, poverty rate, race, and access to public transit. These indicators are similar and complementary to those used in identifying environmental justice communities across the state, as defined in recent environmental justice legislation in Massachusetts.

MassROUTES highlights high-scoring priority areas as places most overburdened by transportation-related air pollution and socioeconomic vulnerabilities as well as underserved by the current transportation system. Compared to other communities in the state, these priority areas would stand to benefit substantially from clean transportation investments. Examples of priority communities identified by MassROUTES include census tracts in Fall River, Brockton, Springfield, and Chinatown in Boston.

The MassROUTES framework builds from that of CalEnviroScreen, a screening tool widely used in California to identify areas with high exposure to environmental hazards as well as various socioeconomic vulnerabilities. MassROUTES incorporates CalEnviroScreen’s cumulative impacts methodology in order to reflect the reality that exposure to transportation-related air pollution is magnified by challenges related to economic, physical, environmental, and social wellbeing. Key differences between CalEnviroScreen and MassROUTES are that MassROUTES includes race, as well as a category of indicators related to transportation vulnerabilities. The final tool is publicly available as a searchable, interactive web application and the final report is also available online. Both of which can be used by policymakers or advocates to focus on more equitable clean transportation policies.

MassROUTES moving forward

While MassROUTES provides a comprehensive method for identifying priority communities, the tool is only as meaningful as the data on which it is based. We see two important ways in which the tool can be improved to be more representative:

- Incorporate meaningful community engagement: Members of priority communities should be able to weigh in on which metrics to include in a tool like MassROUTES, how these metrics are weighted, and how to apply the results of the tool in practice. Inclusive, community-led engagement practices that address these factors would result in more representative decision-making and stronger collaboration between policymakers and priority communities.

- Collect air quality data at the community level: Air quality data is currently drawn from 22 fixed location monitoring stations across Massachusetts (and most other states have a similarly limited number of monitoring stations). Air pollution impacts are more severe closer to the source and can vary greatly, so these fixed stations do not capture pollution levels with the same accuracy everywhere. Investing in air quality data monitoring at a more granular scale, particularly in environmental justice communities, is a critical element in identifying priority communities, making decisions about clean transportation investments, and tracking progress.

Screening tools such as MassROUTES are one way to motivate policymakers to realize and address the gravity of inequitable impacts faced by priority communities. Other states in the TCI region could adapt the MassROUTES methodology to design similar, locally appropriate tools. MassROUTES offers a starting point for engaging communities, crafting planning processes, and guiding policymaking to begin addressing the inequitable impacts experienced by overburdened and underserved communities.