Earlier this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a new rule to limit emissions of the invisible and carcinogenic gas ethylene oxide from facilities that sterilize medical supplies and food. This was a positive step for public health, but it didn’t happen overnight. It was the result of years of work by concerned residents and environmental justice advocates to raise the alarm about the elevated cancer risk from ethylene oxide exposure and call for strong rules to reduce that risk.

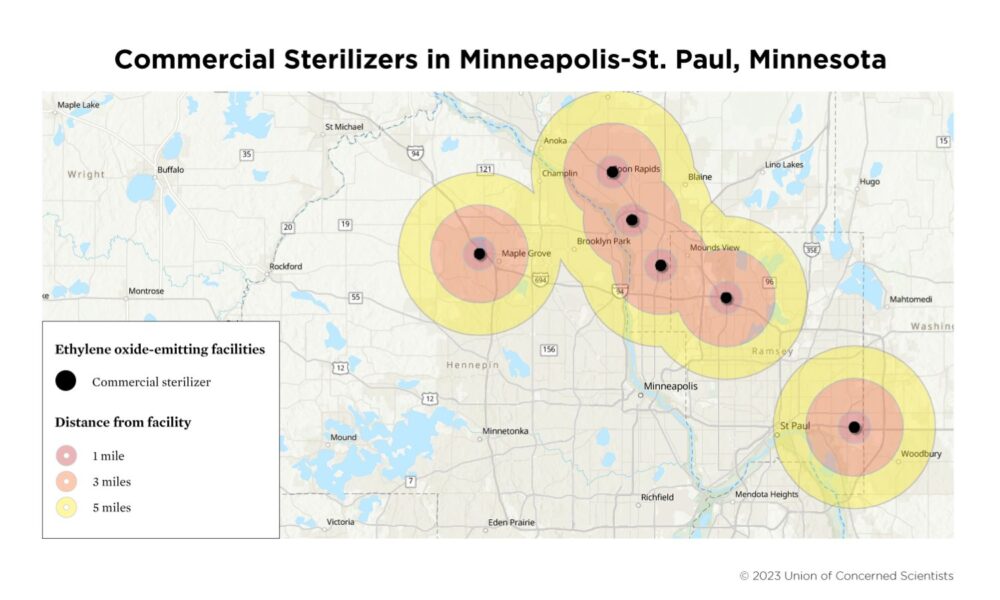

As the UCS report Invisible Threat, Inequitable Impact illustrates, more than 13 million people live within five miles of facilities that use ethylene oxide for sterilization processes. The people living and working around these ethylene oxide-emitting facilities are disproportionately Black or Brown, low-income, or speak a language other than English. For too long, when it came to setting limits on the emissions from these facilities, the federal government listened to the chemical industry, not the people impacted by the pollution created by that industry.

Darya Minovi, senior analyst with the Center for Science and Democracy at UCS, was the lead author on Invisible Threat, Inequitable Impact, and worked closely with community advocates to identify ethylene oxide-emitting facilities and call out the danger they pose. Minovi’s experience working with grassroots activists from impacted communities highlighted for her the importance of public participation in policymaking.

AAS: You worked closely with community organizations on your ethylene oxide analysis. How did that come about? How did those relationships help point you to ethylene oxide as an important issue to highlight?

Darya Minovi: This project came out of years of relationship-building between UCS staff and community groups and coalitions working on toxic substances. We began to investigate ethylene oxide risks in 2018 after speaking to lawmakers and community advocates in Illinois. One of our grassroots partners, Clean Power Lake County (CPLC), is based in Waukegan, Illinois, and had been fighting for stronger regulations for a sterilizer plant in their community for years. When EPA began working toward finally updating emissions standards for commercial sterilizers, we offered to create a map of the sterilizer facilities so that CPLC and other community groups would know where all of these facilities are located and who might be most impacted. That project quickly snowballed into an in-depth analysis, and through that, we identified several communities across the country that had high levels of ethylene oxide emissions from sterilization facilities.

We wanted to give our partners and other grassroots groups in those communities a heads up about what we found, so we spent the few months before the report was published reaching out to groups like Memphis Community Against Pollution, that were already working on ethylene oxide, and others that were broadly concerned about toxics pollution in their communities. We wanted to share our findings, but also to learn from partners about how we could package the information to be most helpful to their advocacy efforts. Through those conversations, we were able to improve our interactive map, translated several of the products published with the report into Spanish, and created factsheets that community groups could use in their efforts. We also directed journalists to speak with these groups directly to share their experience.

AAS: What are the challenges when a community identifies a threat like ethylene oxide?

Darya Minovi: Community groups like Clean Power Lake County, Stop Sterigenics, and California Communities Against Toxics had been working on protecting their communities from ethylene oxide and other toxic emissions for years before UCS came on the scene. One of the biggest challenges groups like these come up against is the power and influence of these industries, and the unnecessary complexity of the regulatory process. These groups are not just fighting for stronger protections from one facility, or one pollutant, but a combination of industrial operations and emissions that are regulated under different laws. That is an exhausting feat, especially when government agencies, especially at the state or local level, might not have the will or resources to meaningfully engage communities in the decision-making process.

In the case of ethylene oxide, however, sterilization facilities were drawing increased attention. In 2019, after EPA data showed alarmingly high cancer risks in Willowbrook, Illinois, around a sterilizer plant, the surrounding community came together and were able to shut the facility down and pass stricter emissions regulations in the state. It was sort of a domino effect where groups started popping up in other communities, as well as a lawsuit brought against EPA by UCS and other groups for the agency’s failure to update these regulations under the requirements of the Clean Air Act. The combination of legal obligation, public pressure and attention, and political will under the Biden administration is what I think finally tipped the scales for action at the federal level.

With commercial sterilizers specifically, there is almost a sense of betrayal that many people experienced. Large chemical manufacturing plants are obvious—you see the smokestacks, you see the plumes, and you have a sense that what’s going on in that facility is at least a little dangerous. Commercial sterilizer facilities, on the other hand, are usually nondescript warehouse buildings with no smokestacks and no clear picture of what is happening inside. These facilities are often in business parks or residential neighborhoods, and in many cases, people had absolutely no idea that a cancer-causing gas was being emitted in their community. I think there was a unique and understandable sense of shock and disbelief for people who learned they lived near a sterilization plant, especially in those communities that had many seemingly “unexplained” cases of cancer.

AAS: You’re going to be doing more research looking at public participation in rule-making processes. What did you learn from the ethylene oxide work about the role that the public, especially impacted communities, should play in these decisions?

Darya Minovi: It quickly became clear to me through this process what’s possible when political will exists. EPA engaged the public in this rulemaking in some ways that I had not seen for other regulations—publishing a list of high-risk facilities, sharing the names and locations of all sterilizer facilities, hosting community meetings in those communities with high-risk facilities, hosting virtual hearings about the rule with ample notice, providing information in multiple languages. It wasn’t perfect, but it was encouraging to see the attention to ensuring the public was aware of the risks of ethylene oxide and the impacts of the proposed rule. And ultimately, the final rule largely prioritized public health concerns and significantly limited ethylene oxide emissions.

However, around the same time, EPA had issued another proposed rule related to ethylene oxide emissions from other chemical manufacturing facilities, and that rule did not receive the same level of fanfare. There was maybe a week’s notice, at most, for the hearings related to that rule, so best practices around meaningfully engaging the public in regulatory processes are not being applied equally. Ideally, EPA and all federal agencies that regulate matters of public health would, at the very least, proactively and transparently share information, host community and virtual meetings, and ensure the information is accessible to people of differing abilities or who do not speak English as a first language.

AAS: How can scientists best support communities who are advocating for their own health and safety?

Darya Minovi: I always recommend first starting with some research to figure out which groups are already active in your community and seeing if there are opportunities to support their work. For folks who would like to work directly with grassroots groups, I recommend that you follow their lead on what issues are most important to the impacted communities. Listen to their priorities, be flexible and collaborative, show up consistently, and do not take for granted the power of relationship building. Be aware that you are not the only expert and learn from how the people you’re working with understand their own lives and communities.

Joining UCS’ Science Network is also a great way to get connected with groups! We were able to connect two Science Network members with one of our community partners to provide expert analysis and testimony on air pollution monitoring data. It was a direct and immensely valuable way they were able to contribute their expertise to help those groups in their advocacy. We’re going to need this collaboration more than ever in the years to come.