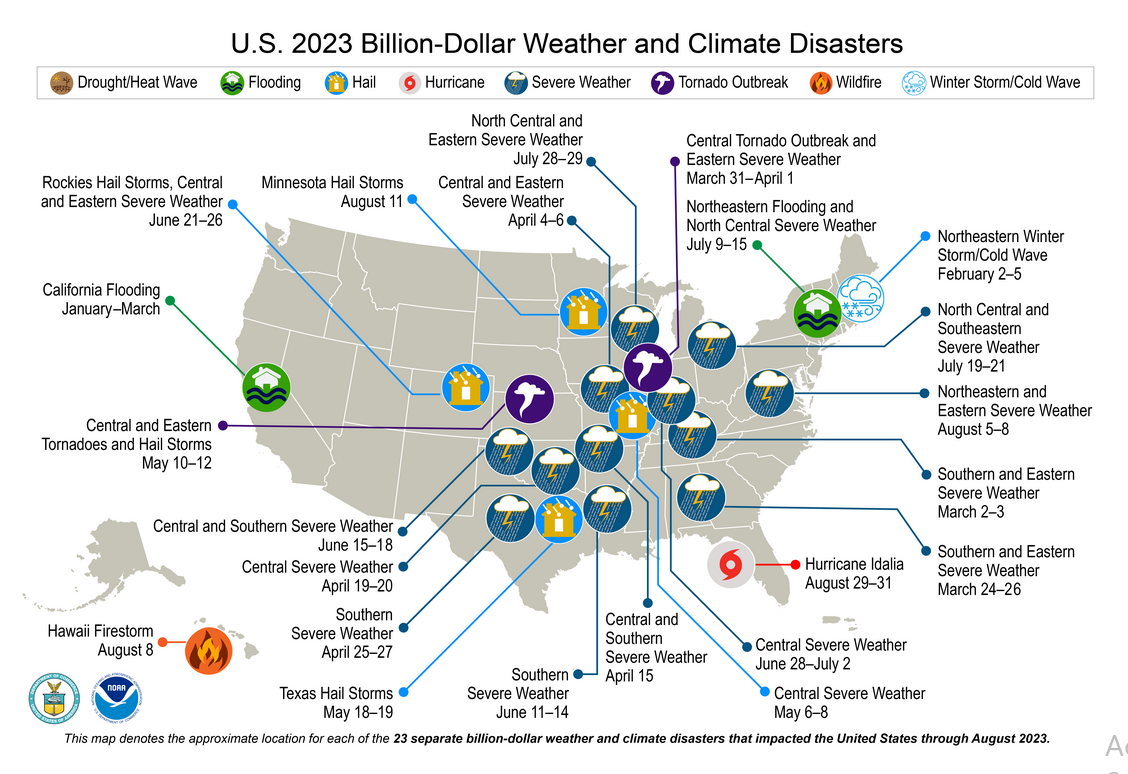

2023 has already been a year of record-breaking climate change-related impacts: endless days of extreme heat, nightmare wildfires, extensive flooding, and storms like Hurricane Idalia that many communities are struggling to recover from. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently released its updated summary of extreme weather and climate change-related disasters. From January to August of this year, NOAA reports that the country experienced 23 disasters that each caused damages of at least $1 billion or more. These disasters had a total economic toll of $57.6 billion and contributed to 253 deaths. With two and half months left in the official Atlantic hurricane season (June 1 through November 30), we’ve already surpassed the total number of billion-dollar disasters for 2022. It’s another extreme weather record for 2023 that we really didn’t want to break—and not this early in the Atlantic hurricane season that NOAA predicts will be above normal.

We need to stay vigilant and prepare now for the rest of the hurricane season, as most storm and hurricane activity occurs between mid-August and mid-October. Preparing for hurricane season to you and me means charging our electronics, making sure we have enough water and ready-to-eat food in our homes, and boarding up windows, among many other actions. For Congress, first and foremost it should mean making sure the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has enough funding in its Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) to respond to presidentially declared emergencies and disasters.

FEMA releases a daily briefing of the disasters the agency is monitoring and responding to, which often includes the spending obligations and allocations for programs under the DRF. The four primary programs help communities in many ways—for example, helping individuals secure housing, investing in state and tribal life-sustaining actions, and funding recovery efforts that rebuild infrastructure to reduce future risk. The programs include Individual Assistance (IA), Public Assistance (PA), the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), and the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program.

In August, given the devastating spate of disasters the nation experienced this year, the funding available in the DRF was running low. President Biden and FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell made an urgent request that Congress appropriate $12 billion in additional funds to FEMA’s depleted DRF. On September 1, the President urged Congress to include an additional $4 billion to replenish the fund to $16 billion, given recent disaster activity. Unfortunately, the updated NOAA data on costly damages, the active Atlantic hurricane season, and urging by President Biden and FEMA have seemingly gone unseen and unheard, and we have yet to see any real momentum by Congress to replenish the funding for disaster relief.

What’s at stake: delaying disaster relief exacerbates inequities

There’s no doubt that FEMA is reckoning with how to fulfill its mission as climate change continues to fuel more disasters. Last week, FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell testified in Congress to the state of FEMA’s disaster readiness, response and recovery and spoke to the reality the agency is facing: “We can no longer really speak of a disaster “season.” On average, we are seeing a disaster declaration every three days.”

In her testimony, Administrator Criswell also stated that given the low DRF levels and lapse in appropriations, FEMA has been forced to prioritize its funds for life-saving efforts, and put on hold recovery funding for previous disasters. For example, she noted that FEMA hit the pause button on $1.5 billion worth of public assistance projects (a total of 1,000) to repair facilities damaged or destroyed by past disasters across the country, including Hurricanes Ida, Ian and Laura. It’s also possible that FEMA will need to redirect risk reduction funding from the BRIC program to help pay for immediate response and recovery needs.

The delay of this assistance will impact those who often get overlooked, people experiencing homelessness and the many people who become displaced post-disaster, as well as underserved and historically disadvantaged communities who tend to live in higher-risk areas, have less means to prepare for a storm, and have little to no savings to recover after a disaster.

The nation needs a paradigm shift (but until then)

We need to change the paradigm from investing the majority of federal grant funding in post-disaster response to investing more funds in pre-disaster risk reduction, preparedness, and resilience, so that the nation is on the right path to being better prepared to withstand hurricanes, flooding, wildfires and other extreme weather events. Realistically, we’re miles away from that paradigm shift given the complexity of federal disaster assistance, which is spread out over 30 federal agencies and departments. However, there are a few solutions that could be implemented in the short term to improve disaster response and preparedness.

What FEMA can do in the short term:

- FEMA should calculate its annual budget request for the DRF based on modeling of future conditions to better reflect the non-stationarity of climate change—that is, we can’t rely on the past to project the potential impacts in the future. Such an approach could help FEMA develop a more realistic budget for DRF funding and would also be in line with the Biden administration’s effort to more fully account for climate change in a wider range of actions, including budgeting. Congress should then fully fund this request.

- FEMA must also address how well the agency is meeting the goal of the Biden administration’s Justice40 initiative, which requires FEMA to target 40 percent of the resources under four of its programs to disadvantaged communities. In the past, analysis found that many of the FEMA grant programs, including the popular BRIC program, have proven to be difficult for under-resourced communities to access. This year, FEMA improved the BRIC program allocation targeting 71% of the grant submissions to disadvantaged communities. While it is great to see this effort by FEMA to fulfill Justice40, a full assessment of its four programs under the initiative would benefit FEMA and the communities it serves.

- FEMA must also work in a strategic fashion with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to more effectively address federal disaster shelter and housing assistance for the unhoused population.

In addition to authorizing funding for FEMA’s DRF, Congress should prioritize these three actions.

- First, Congress needs to reauthorize the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which is set to expire September 30th. If Congress fails to reauthorize NFIP and there’s a lapse, there would be two main consequences: by law FEMA would be required to stop the issuance of new policies, and would be limited on its borrowing authority from the US Treasury from $30 billion to $1 billion. The lapse in new flood policies could impact the successful closing of an estimated 40,000 home sales per month due to the fact that anyone taking out a federally backed mortgage for a home with considerable flood risk (in the Special Flood Hazard Area) must purchase flood insurance. If NFIP lapses, or if FEMA’s fund to pay claims gets depleted and FEMA reaches its borrowing authority limit, FEMA would be forced to delay paying flood insurance claims, a distressing scenario for insurance holders in the middle of the Atlantic hurricane season.

- Second, Congress should pass the Reforming Disaster Recovery Act (S. 1686) that would permanently authorize the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program which states, tribes, and communities rely on for flexible, long-term recovery resources to rebuild affordable housing and infrastructure after a disaster. For years, the bill has had broad support, including from the Disaster Housing Recovery Coalition (DHRC), a coalition of more than 850 local, state, and national organizations across the country.

- Third, Congress should authorize an increase in the set-aside funding for FEMA’s BRIC program that has been overprescribed in the last few years due to the level of interest in this federal matching grant program for risk reduction and resilience measures. For example, a bipartisan effort in the last Congress introduced and passed in the House the Resilient AMERICA Act that would have increased the set-aside from six percent to 15 percent, among other actions.

With an active Atlantic hurricane season and endless recovery needs, Congress must act

Congress needs to immediately authorize $16 billion in supplemental funding for emergency spending to replenish the DRF, and pass an appropriations bill to keep the government open and help keep the program solvent.

Congress has a limited window of opportunity to get this basic work done. Leaving the nation’s disaster recovery fund on fumes is adding salt to the wounds of communities trying to recover from devastating disasters—including the wildfires in Maui that destroyed Lahaina and caused an estimated $4-6 billion in damages, or Hurricane Idalia, which caused an estimated $9.36 billion in insured housing losses in Florida alone. While federal disaster policy won’t be fixed overnight, replenishing the DRF and passing spending bills to keep the government open can be. Congress must not keep communities trying to recover from disasters waiting and wondering about whether they’ll receive help in their time of need.