As I write this, it’s 83 degrees Fahrenheit in Washington, DC, and I can’t help but long for those years when I was a kid, when spring felt like spring and seasons were demarcated. Each year, summer-like temperatures arrive all too soon during spring, thanks to human-induced climate change. Research finds that even if we halt heat-trapping emissions, we’ll be locked into a summer season that consumes half of the year by 2100. While that may seem far in the future, the current conditions are enough to cause alarm.

Last year brought the dangers of extreme heat to the forefront. Again. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 2021 followed the distressing trend of excessive heat, as the sixth hottest year on record (a tie with 2018). Even more alarming is that the past eight years are the warmest on record since modern recording began in 1880.

That’s why this week, my colleague Juan Declet-Barreto and I were pleased to accept an invitation from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Office of the Assistant Secretary to attend a special event highlighting the administration’s efforts on labor and extreme heat. The email invitation recognized UCS “research highlighting the effects of extreme heat on workers, and advocacy in calling for more worker protections.” Our advocacy efforts were part of a larger Public Citizen campaign to unite a national network of organizations to protect workers from heat stress in a warming climate.

The event was hosted by Vice President Kamala Harris and Labor Secretary Marty Walsh at the Sheet Metal Workers International Association in Philadelphia. I was eager to hear about the administration’s newly established National Emphasis on Heat Program under OSHA. Vice President Harris announced that OSHA will conduct workplace heat inspections nationwide, and would start by targeting more than 70 of the highest at-risk industries. Citing statistics in line with our recent Killer Heat scientific research, the Vice President underscored the dire need for OSHA’s workplace heat inspection program:

“[E]very year, thousands of workers suffer heat-related injury and illnesses. The danger posed by extreme heat has been ignored and overlooked for far too long. And that danger is only increasing. Because as we know, climate change has become a climate crisis. By 2030, this very city can expect 25 days a year with heat and humidity that will make it feel like 105 degrees or hotter. Think about that.”

In less than a decade, 20 percent of Philadelphia’s workforce employed in outdoor occupations–roughly 136,000 outdoor workers–will find that it is too hot to work, and could face the choice of losing pay, losing their job, or worse, experiencing a harmful or even deadly heat-related illness. These jobs range from protecting the public, maintaining buildings, harvesting our food, constructing buildings and directing traffic, among many more.

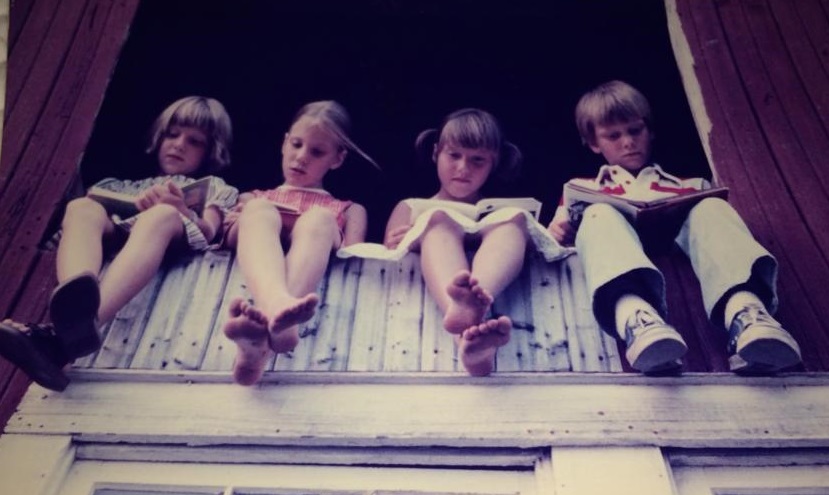

However, we know heat will affect everyone, not just outdoor workers. Elderly people and children can be particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. While the future is daunting even if we halt heat trapping emissions tomorrow, we can find some solace in the President’s commitment “to Protect Workers and Communities from Extreme Heat,” which provides a comprehensive federal strategy to implement a range of measures that will help to protect workers from extreme heat.

What more needs to be done?

This is the question Justin Udo with Philadelphia’s KYW News Radio asked me after the Vice President’s announcement. Here’s my expanded, four-point answer.

- First: We know that, within this decade, we must rapidly cut heat trapping emissions and reduce them to net zero by roughly 2050 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, in line with the Paris Agreement. Congress has been stalling on advancing a climate bill and time is of the essence to swiftly advance it, as my colleague Rachel Cleetus explains in this must-read blog post. The bill must include provisions to ramp down the power sector’s carbon emissions and ensure a just and equitable transition to clean energy. Extreme heat will have a significant impact on the health, lives, and livelihoods of the 32 million outdoor workers in the United States. Congress must work to protect future generations by passing a legislation to address climate change, to drive down heat trapping emissions and invest in adaptation measures.

- Second: We need two heat protection bills to be enacted into law: Congress must pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act of 2021 (S. 1068) to require OSHA to establish a heat protection standard for indoor and outdoor workers, and require employers to provide training and education to prevent and respond to heat illness and ensure whistleblower protections. Congress must also pass the Preventing HEAT Illness and Deaths Act of 2021 (S.2510), which will help reduce heat health risks by creating a new National Integrated Heat Health Information System Program and committee to comprehensively improve heat preparedness, planning, and response.

- Third: OSHA must rapidly advance the rulemaking process for a workplace heat safety standard. You can read more about what OSHA ought to include in such a standard by reading the robust comments by my colleague Kristy Dahl.

- Fourth: Congress and the public must hold oil companies accountable for their disinformation campaigns and contribution to the climate crisis. My colleague Kathy Mulvey has written about how the fossil fuel industry must face climate liability claims given their harm to the planet and decades-long failure to warn investors of climate risks.

This new OSHA initiative is a great step forward towards holding some of the most egregious industries and employers accountable. We must ensure OSHA’s inspection program leads to immediate, concrete changes in industry practices and quality of employers’ facilities, whether it’s shade and water breaks for grape pickers or working air conditioners for factory workers. Protection from extreme heat will only become more challenging with climate change. Getting Congress and federal and state agencies to act quickly is critical, especially for those who have the least ability to advocate for themselves.