The nation is grappling with yet another year of climate change-fueled disasters with billion-dollar price tags, from the extreme heat and wildfires out west and back-to-back hurricanes. At this moment, the last thing federal, state and local governments need is to divert precious resources to debunk baseless conspiracy theories and disinformation. Regrettably, this is where we find ourselves. President Biden, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and state and local government representatives have been busy trying to communicate the truth about the response and recovery efforts related to Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton. Due to the extent of the baseless rumors, FEMA posted a “Hurricane Rumor Response” webpage which helps to nullify the disinformation and provide valuable information.

To help make sense of disaster assistance and FEMA’s role, I provide answers to six questions to help clarify the federal disaster recovery process.

1. What happens when a disaster hits?

The process of how disasters are declared and what happens once they are, may be a bit mysterious but briefly here are a few things to know. The President can issue an emergency declaration or major disaster declaration for a range of disasters, for example climate change-related disasters like Hurricane Milton and Helene and the wildfires in Maui, natural hazards like earthquakes and other incidents like the Baltimore bridge collapse and major societal and public health disruptions like the Covid-19 pandemic. The Stafford Act (officially, the “Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act”) is the law that gives the President the authority to provide disaster response, recovery and preparedness assistance to state, local, tribal, or territorial (SLTT) governments.

An emergency is defined as:

“any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, Federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States”.

A major disaster is defined as:

‘‘any natural catastrophe (including any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, wind driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought), or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion, in any part of the United States, which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this Act to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damage, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby.”

The request for a major disaster declaration comes from the Governor of the state that’s been impacted and signals to the President that the impact is beyond the means of the state’s ability to manage (the process for an emergency declaration is similar):

“(a) In General – All requests for a declaration by the President that a major disaster exists shall be made by the Governor of the affected State. Such a request shall be based on a finding that the disaster is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the State and the affected local governments and that Federal assistance is necessary.” “Based on the request of a Governor under this section, the President may declare under this Act that a major disaster or emergency exists.” [see Sec. 401. Procedure for Declaration (42 U.S.C. 5170)].

Once the President provides the declaration, authorities are delegated to FEMA and FEMA will utilize the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) to release federal assistance to the SLTT governments in need.

2. What is the Disaster Relief Fund?

FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) is the federal government’s primary source of funding for disaster response, recovery and preparedness. Congress provides appropriations annually to the fund and often provides supplemental funding when disasters mount and costs begin to drain the available funds. The fund primarily supports major disaster needs for FEMA’s direct disaster programs and a small portion is dedicated to support FEMA’s readiness activities.

FEMA’s direct disaster programs include public assistance (PA), individual assistance (IA) and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP). Briefly, PA provides funds for large projects like repairing critical infrastructure and debris removal. IA is a source of funding for individuals and households. Individuals can receive immediate assistance with a one-time $750 cash payment for emergency supplies. An individual or family can also receive additional funds under IA by registering with FEMA to help pay for repairs to homes that have been damaged by storms, personal property replacement and for temporary housing. The HMGP is a pot of funding to help reduce future losses through preparedness activities. A major disaster declaration makes all three disaster programs available to impacted communities while an emergency declaration releases both public and individual assistance programs.

The Stafford Act requires SLTT governments to share the disaster relief responsibility by covering 25 percent of the cost. FEMA provides the remaining 75 percent. If the disaster is particularly devastating, the President may lower or waive the cost share altogether.

After much public advocacy to reduce future impacts and invest in preparedness, in 2018 Congress passed critical legislation that established the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities “BRIC” grant program to allow the President to set aside 6 percent of the DRF specifically for pre-disaster, preparedness and resilience efforts. Under BRIC, FEMA prioritizes innovative, equitable and nature-based infrastructure projects. For example, communities can use funds to increase energy resilience while also reducing emissions by advancing energy efficiency and microgrids, for example. As one of the FEMA programs under Justice40, FEMA ensures a minimum of 40 percent of the benefits are targeted to historically disadvantaged communities. FEMA also prioritizes funds for other critical resilience activities that are often underprioritized such as implementing building codes and conserving and restoring wetlands and dunes.

3. Is FEMA the sole federal agency available for disaster response and recovery?

FEMA has the lead authority for disaster response and recovery (under the Stafford and the Homeland Security Acts). The Presidential Policy Directive on National Preparedness provided a coordinated “whole of government” disaster assistance approach that includes thirty federal agencies. Other federal agencies provide rebuilding and longer-term recovery support under their own authority and Congressional appropriations or FEMA’s “mission assignments” in which it will reimburse agencies for specific efforts.

For example, the US Army Corps of Engineers (the “Corps”) has its own authority under the Flood Control Act and Coastal Emergencies law to provide disaster preparedness services to reduce the amount of damage caused by an impending disaster. After hurricanes or other disasters, the Corps will often provide emergency power, critical infrastructure inspections and debris management under its own authority. The Corps also fulfills FEMA’s Operation Blue Roof mission assignment to help owners with temporary roof repairs.

Many of the other critical federal programs that individuals and communities rely on after a disaster are dependent upon Congressional supplemental funding. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) grant program provides flexible funds to disaster impacted areas, particularly low-income communities, to help people and neighborhoods rebuild after a disaster. The Small Business Administration (SBA) provides low-interest loans for disaster assistance to homeowners, businesses, non-governmental organizations and renters.

4. How is the Disaster Relief Fund funded and what happens when it runs low?

Congress appropriates funding annually to the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF). Unfortunately, the DRF typically runs low before September 30th, the end of the Fiscal Year (FY) even though FEMA (as mandated by Congress) provides monthly DRF status reports and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides seasonal outlooks, such as the Atlantic hurricane season that predicted an above-normal 2024 Atlantic hurricane season. Budgeting sufficient funds to the DRF is complicated by the fact that the federal government’s fiscal year ends right in the middle of Danger Season (the months from May to November when we expect an increase in climate change-related events) and because FEMA estimates the DRF budget based on the past ten years rather than proactively estimating future funding needs based on future climate change and development projections. It’s perhaps not surprising then that Congress has provided the majority of DRF funding through the often last minute, politically fraught supplemental appropriations.

During these times, the FEMA administrator is sometimes forced to place the DRF under Immediate Needs Funding (INF) restrictions, which is a last-resort measure that delays distributing obligated funds to communities for large recovery projects and instead applies these funds for immediate disaster response, lifesaving and life-sustaining efforts. According to FEMA, since 2001, the agency has implemented INF restrictions 9 times, including last year. This puts unnecessary stress on FEMA, which is already spread thin particularly during Danger Season. Congress must do better to provide FEMA with sufficient funding to respond to risk in a timely and equitable way before Danger Season starts (More on this in question 6).

5. Are disaster costs rising and if so, why?

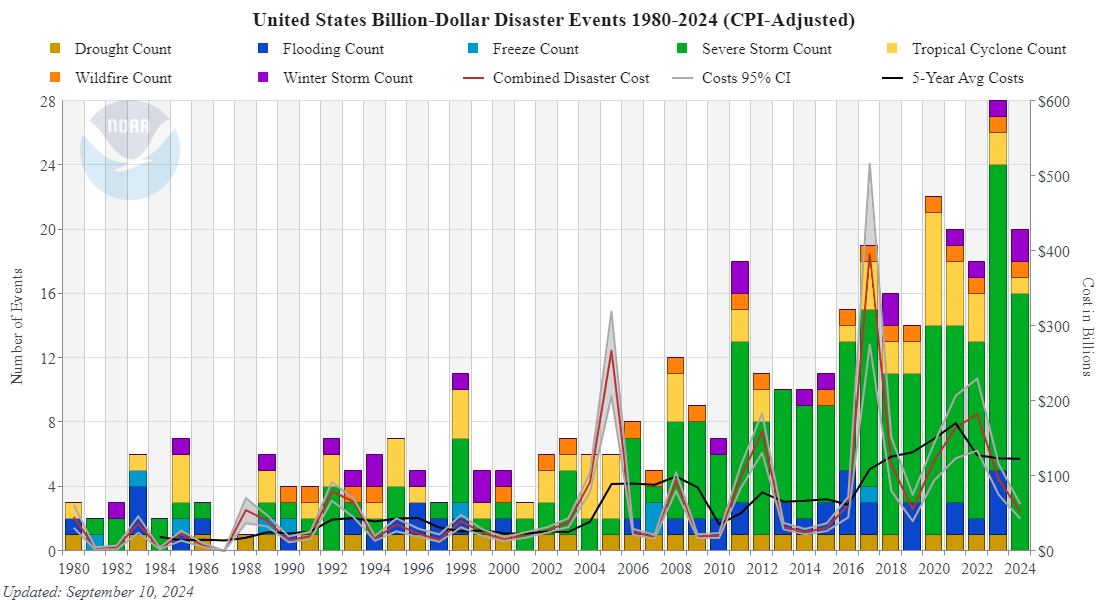

Yes. Unfortunately, disaster costs have been steadily rising.

Already this year, the President has declared 117 disasters, 87 of which have been major disaster declarations (compared with 71 major disaster declarations in 2023, 47 in 2022, 58 in 2021 and 104 in 2020). Before the devastating Hurricanes Helene and Milton, NOAA estimated (as of September 10, 2024), that in 2024 there were 20 separate billion-dollar climate change-related disasters that collectively contributed to the deaths of 149 people with a total economic cost of $53 billion.

Sadly, we know that the lives lost and costs of damages for this year are only going to increase as states begin to tally damages from Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton and as we wait out the rest of the Atlantic hurricane and wildfire seasons. Last year, we experienced 28 separate billion-dollar disasters which resulted in over $93 billion in damages.

While 2022 had fewer billion-dollar disasters (18), it was a record-setting year for the cost of damages with a total cost of $165 billion. That made 2022 the 3rd most costly year on record behind 2017, when Hurricane Harvey landed as a Category 4 storm, and 2005 when Hurricane Katrina landed as a Category 5 storm.

We’re seeing how climate change is reaching more and more communities leaving no one untouched and having lasting impacts, especially on low-income communities, communities of color, and Tribal communities, due to both their proximity to hazard-prone areas and lack of adequate infrastructure and/or disaster management resources.

In brief, the unfortunate recipe for these increasing costs is threefold:

- We’re putting more and more buildings and people in harm’s way

- These buildings and assets aren’t built to modern building codes, and some infrastructure was built 50 to 100 years ago, and

- Climate change amped by fossil fuels is increasing the likelihood of intense hurricanes, heaviest rainfall events and extreme wildfires, for example

Climate change is also increasing the chances of multiple climate hazards occurring simultaneously or consecutively across the US—meaning there’s less time between disasters. According to Climate Central, over the last 5 years there were 16 days on average between US billion-dollar disasters, compared with 82 days in the 1980s. In 2023, that number shrank to just 12 days between disasters. This is significant, as having less time between disasters has major implications the amount of time and resources federal and SLTT governments have available to respond, recover quickly, and prepare for future risks.

6. What can we do?

First and foremost, we must reduce heat-trapping emissions. The sobering reality is that people everywhere are feeling the impacts of a warming world. We need all levels of government and the private sector to turn the dial down on global warming by rapidly reducing heat trapping emissions. The latest science shows that, globally, heat-trapping emissions must be cut by about half by 2030 and reach net zero no later than 2050 to have a fighting chance of keeping the 1.5C goal alive.

Second, while it’s not likely that Congress will come up with a new way to respond to disasters in the near term, there’s a lot Congress can and must do in the near-term. As Colt Hagmaier, FEMA’s Assistant Administrator of the Recovery Directorate within the Office of Response and Recovery (ORR) said: “Restoring hope doesn’t happen by chance but by action and individual commitment to humanity.” Congress should:

- Anticipate the likely need for more funding ahead of Danger Season and be ready to provide supplemental appropriations when the FEMA administrator requests additional funding for the DRF. Disasters affect all states—red and blue—so this should not devolve into a lengthy partisan fight while people on the frontlines of disasters wait and suffer,

- Provide supplemental funding and permanently authorize HUDs CDBG-DR program, which is often the only lifeline for low-income families and communities post-disaster.

- Work in a bipartisan fashion to reform the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) by, at a minimum, modernizing and funding flood risk mapping, incentivizing flood risk disclosure, providing innovation and resources for flood risk mitigation and provide FEMA with the authority to offer affordable flood insurance to those who can least afford it.

Third, while FEMA can be commended for advancing reforms to its disaster assistance grant programs, there’s no shortage of additional actions the agency can take. FEMA should:

- Adjust their funding requests based on future climate projections instead of averaging the costs over the past ten years.

- Utilize its authority to include advisory layers on flood maps based on future climate change projections.

- Modernize the NFIP minimum floodplain management standards which haven’t been updated in 50 years.

- Systematically increase and broaden its staff to ensure the agency has the expertise it needs to improve upon Justice40 and other equity goals in addition to being able to manage the increasing complexities that come with the climate crisis.

We need bipartisan action

My heart is heavy as I think of the communities hit by these record-breaking disasters because we know that recovery from a devastating hurricane, wildfire or any disaster is long and arduous.

While UCS will continue to push for reforms to current federal policies and advocate for new federal disaster recovery policies, the good news is that we’re not alone in these efforts. For example, at the national level, the Disaster Housing Recovery Coalition (DHRC) under the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) brings together 850 national, state, and local organizations to help disaster-impacted communities recover.

We have the solutions; we urgently need bipartisan actions at all levels of government to help give people the change they want to see.