This blog was co-authored with UCS China Analyst Robert Rust.

Open-source estimates of China’s past fissile material production indicate that China does not have enough plutonium to make the more than 1,000 nuclear warheads the Pentagon claims China will deploy by 2035. The extra plutonium needed to produce new weapons, the Pentagon says, will come from China’s new fast breeder reactors, a type of nuclear reactor that produces more plutonium than the uranium and plutonium it consumes for fuel. Recently, US official Vipin Narang claimed that Russia, which has a contract to supply the highly enriched uranium (HEU) for those reactors, is “literally” fueling China’s nuclear weapons program.

Framing Russia’s export of highly enriched uranium to China in this way is misleading. This arrangement was negotiated 25 years ago and is part of a decades-old program of cooperation on nuclear technology, which includes agreements not to use this assistance for military purposes. Additionally, fast breeder reactors, while theoretically capable of producing excess quantities of plutonium that could be diverted to weapons, are not optimized for the purpose due to their technical complexity and the existence of more efficient alternatives for producing weapons-grade material. Narang’s claim, which implies that Russia and China intend to work together to build up China’s nuclear arsenal, ignores the historical and technical context of their cooperation.

Both Chinese and international sources indicate that the country’s nuclear industry has been planning to develop fast neutron reactors (of which fast breeder reactors are one type) since the 1960s. Russian-Chinese technical cooperation on fast breeder reactors began in 1992, and the agreement to provide Russian highly enriched uranium for these reactors was negotiated in 1999. This predates by nearly 20 years the US intelligence agencies’ discovery of several hundred new missile silos in the deserts of western China, which form the basis for claims that China plans to rapidly expand its nuclear arsenal.

Connecting these two developments ignores this long history of Russian-Chinese cooperation on nuclear energy, taking the agreement to supply highly enriched uranium out of its historical context.

Cooperation between Russia and China on fast breeder reactors

Civilian nuclear agreements and cooperation between countries are not uncommon, especially between nuclear supplier countries and those looking to expand and develop nuclear power programs. These agreements often involve the transfer of reactor technology, supply of nuclear fuel, and training of specialists to operate the reactors.

Since the 1990s, there has been significant cooperation between Russia and China on civilian nuclear energy. In 1992, after five years of research, China decided to cooperate with Russia on the construction of an experimental fast reactor (CEFR), with the ultimate goal of pursuing a closed nuclear fuel cycle—a process in which spent nuclear fuel is reprocessed and recycled to extract usable materials for further energy production. Together with specialists from OKBM Afrikantov, a nuclear engineering company in Russia, the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE) developed the concept and technical requirements for the reactor. Since 1999, after the Chinese government approved the reactor plans, TVEL, Russia’s nuclear fuel company and a Rosatom subsidiary, worked with the China Institute of Atomic Energy to supply highly enriched uranium fuel (64.4% U-235) for China’s CEFR. Transfers of highly enriched uranium happened in July 2004, March 2014, and July 2019. The CEFR reached criticality in July 2010 and connected to the grid in July 2011. While this reactor was initially intended to transition to mixed oxide (MOX) fuel by 2015, delays in development led China to continue relying on Russian fuel. The cooperation was extended in December 2016.

While the operation of the CEFR and supply of highly enriched uranium to the reactor attracted less attention from foreign media, the construction of the two China Fast Reactor (CFR)-600 reactors in Xiapu, China, in 2017 sparked widespread discussion. Unlike the CEFR’s small generating capacity of 20 megawatts, the CFR-600 reactors represented a significant increase in scale, to a demonstration stage of 600 megawatts from each reactor. From a military perspective, the increased scale also meant a greater ability to produce plutonium, which raised concerns about their potential dual-use (i.e., energy and weapons) capabilities. This was perhaps heightened by China’s decision to stop voluntarily reporting plutonium to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 2017.

While this decision to halt voluntary reporting deserves scrutiny, it does not directly indicate that China plans to use the plutonium for nuclear warheads. Instead, it may reflect China’s shifting strategic calculus regarding transparency. Moreover, China is notoriously secretive about its nuclear weapons program, and its agreements with Russia on developing and fueling these reactors were executed with no apparent effort to conceal the details.

Unlike the CEFR, China is trying to develop the CFR-600 independently, with some help from Russia, including highly enriched uranium to fuel the new reactors. In 2018, Russia agreed to supply fuel for the CFR-600 for seven years. The initial core loading of fuel, likely containing around 30% U-235 or less, was supplied by TVEL in 2022. One of the CFR-600s may have reached criticality in mid-2023, though whether it is connected to the electricity grid remains unclear.

Where China gets its uranium

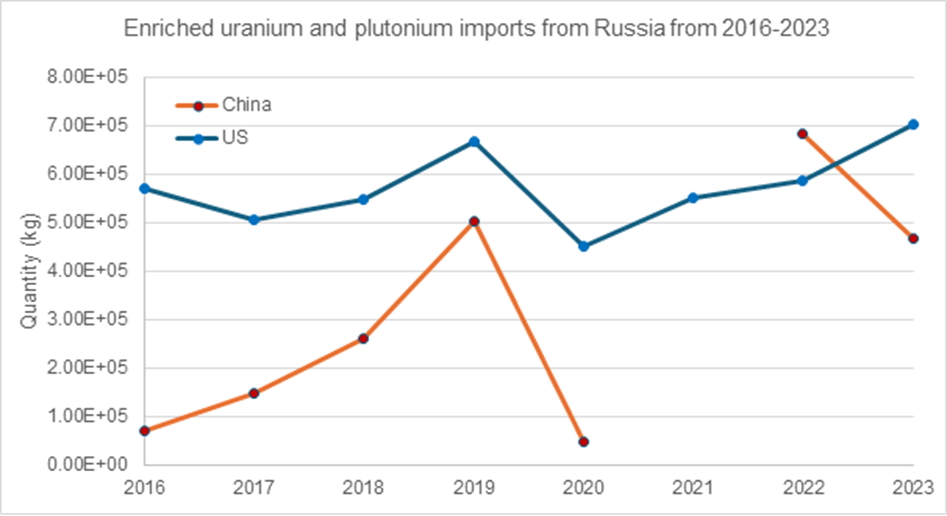

Russia and China’s nuclear cooperation has deepened in recent years. China’s imports of enriched uranium from Russia in 2022 and 2023 increased compared with pre-2020 levels, as seen in Figure 1. The United States is actually one of the largest importers of Russian enriched uranium (though it is actively working to reduce that dependency), followed by the European Union, which sourced more than 30% of its enriched uranium and related services from Russia in 2022. Overall, Russia exported enriched uranium worth $2.7 billion in 2023. However, it should be noted that these numbers do not account for the level of enrichment—China’s imports from Russia include highly enriched uranium, raising distinct concerns compared with lower enrichment levels.

Figure 1. US and Chinese imports of Russian-enriched uranium and plutonium. Source: World Bank

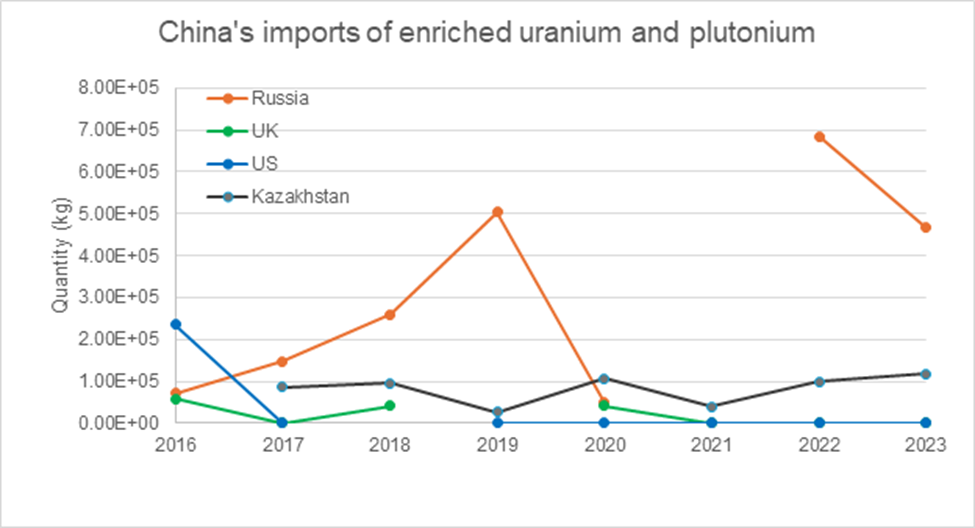

China’s import of enriched uranium is not limited to Russian sources, though a huge portion does come from Russia. As seen in Figure 2, the country also procures enriched uranium from other major suppliers, including Kazakhstan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Notably, China’s import of enriched materials from the United States has decreased substantially since 2016.

Figure 2. Chinese imports of enriched uranium and plutonium, all sources. Source: World Bank

Regulatory framework and legal restrictions

There are legal and regulatory restrictions in place governing Chinese use of highly enriched uranium from Russia. Russian export laws and bilateral agreements with China explicitly prohibit the use of supplied materials for military purposes. Specifically, as discussed by the International Panel on Fissile Materials, the Agreement on Cooperation in the Area of Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy, signed by Russia and China in 1996, prohibits the use of exported nuclear items for nuclear weapons or “any military purposes.” Russia’s Regulations on the Export and Import of Nuclear Materials, released in 2000 and last amended in February 2023, contain a similar provision against the use of exported nuclear materials or their byproducts for military purposes. These provisions against military use are also present in a 2018 contract for Russia to provide fuel for the CFR-600 reactors.

China also has domestic uranium enrichment capabilities and is expected to expand its capacity substantially in the next decades. Yet China continues to import highly enriched uranium from Russia for several possible reasons. The first is economic: importing from Russia may currently be more cost-effective than domestic production. The second is strategic resource management: China has long aimed to diversify its resources to manage risks associated with relying solely on domestic production. Importing highly enriched uranium can provide a buffer against potential disruptions in the domestic supply chain while ensuring a reserve for future use. Lastly, political and diplomatic considerations might play a role: cooperation with Russia on nuclear technology and material could be a part of a broader strategic agreement to strengthen the relationship between the two countries and contribute to advancing reactor technology.

The trade of enriched uranium and nuclear agreements are common features of global nuclear energy markets, and Russia plays a significant role as a supplier to China. While the supply of highly enriched uranium from Russia to China is noteworthy and continued monitoring is necessary, it should not be viewed in isolation as evidence of a covert effort to advance China’s nuclear weapons program. The discussion about China potentially using its fast breeder reactors to obtain plutonium with Russia’s assistance is not supported by the contractual details, nor would this be the most efficient way for China to obtain plutonium for warheads. China’s unwillingness to engage with the United States on bilateral arms control does not imply a nuclear weapons–based alliance with Russia against the United States.

China’s diversified sources of enriched uranium, the global norms governing nuclear trade, and the adherence to strict regulatory frameworks collectively indicate that Russia’s highly enriched uranium supply is part of a routine, civilian nuclear energy partnership. The broader context of international nuclear cooperation and trade illustrates that the focus should remain on maintaining and strengthening regulatory measures rather than assuming nefarious intent based on bilateral cooperation between Russia and China alone.