At 11 a.m. on December 30, 2021, I drove from my family’s home in Fort Collins, Colorado, to the Denver airport, excited for a trip to visit a friend. I boarded the plane around 1:45 p.m. The woman next to me asked if I was from Colorado (I am!) and then pointed out the window. “Is that from a fire?” she asked.

I looked out and noticed for the first time a smoggy haze on the horizon. What?

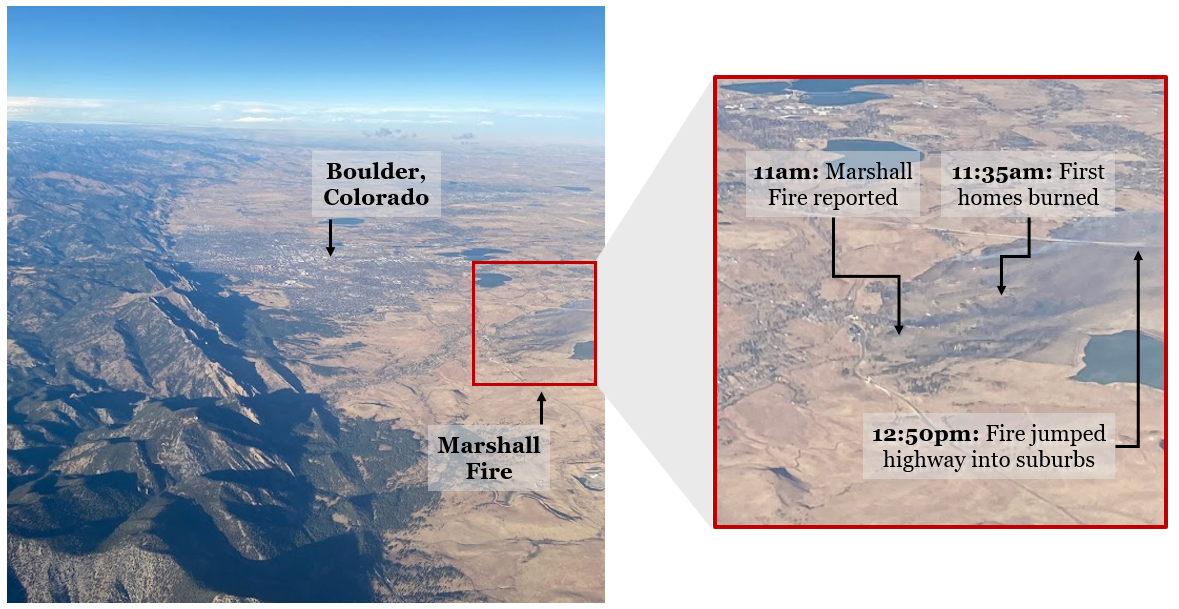

It couldn’t be a wildfire, I thought. It’s December. So I mumbled a hasty answer: “It might be dust because it’s so windy!” The plane took off and, dazzled by the view, I snapped a photo from the window.

It was only when I landed that I learned what had happened. When I’d left for the airport around 11 a.m., someone reported a “small fire” in a patch of grassland a few miles southeast of Boulder. Half an hour later, the first home burned. At 12:15 p.m., someone in the town of Superior—miles from where the fire began—told 911 dispatchers that their backyard was on fire. At 12:50 p.m., the fire jumped a highway and reached the town of Louisville. Tens of thousands of residents received reverse-911 calls ordering them to evacuate immediately. Winds reaching 100 mph carried the flames eastward. Firefighters couldn’t get ahead of it.

Over the next few hours, 1,000 homes burned to the ground.

When I looked at the photo I’d snapped from the plane, I noticed something I hadn’t before: a pocket of smoke stretched across the plains. I had inadvertently snapped a photo of homes burning in the Marshall Fire, the most destructive fire in Colorado’s history.

A long-simmering crisis

Wildfire has always been a leading character in the story of the West. For eons, fires have swept across great swaths of wildland, clearing out old trees, killing pests, and letting new life take root.

But climate change is rewriting the story. A megadrought has plagued the West since the turn of the century, representing its driest period in at least 1,200 years, and nearly half of the drought’s severity is attributable to climate change. In Colorado, the seasonal rains that for millions of years shaped the evolution of ecosystems, and for thousands of years the livelihoods of people, have become erratic. In some parts of Colorado, “climate hot spots” are warming faster than the rest of the world. The state’s Western Slope has warmed more than 2 degrees Celsius, double the global average. And my colleagues at the Union of Concerned Scientists say this will only get worse.

Meanwhile, mountain snowpack—slow-melting snow that releases water through spring—is dwindling, leaving the land thirsty and dry (and drinking-water supply dangerously low). According to Dr. Steven Fassnacht, a snow hydrologist at Colorado State University, snowpack has been decreasing over the past 40 or so years, and less snowpack generally means more, and larger, fires.

This is all great news for bark beetles, which thrive by boring into trees’ inner bark and killing them. More beetles survive warmer winters, and the bugs have spread into areas that were previously too cold for them. Worse still, the drought has weakened trees that could, under normal circumstances, fend off the pests.

Consequently, forests are thrashed by a three-pronged weapon: heat, pests, and drought.

Before climate change, says Dr. Adam Mahood, a fire ecologist at the University of Colorado, trees weathered an intense drought every couple hundred years or so. But now, trees have no reprieve. “Instead of one bad year and then 300 years to recover,” says Dr. Mahood, forests are battered year after year by drought and intense heat. According to a study published in 2021, tree deaths in Colorado’s subalpine forests have more than tripled since the 1980s. Bark beetles caused nearly a quarter of tree deaths over the 37-year study period. Heat and drought were responsible for more than 70 percent.

All of this has left Colorado’s forests and scrublands tinder-dry and prone to wildfires. Before 2000, the state hardly ever had wildfires that burned more than 10,000 acres. Since 2000, though, the state has endured more than 60 such fires. Before the Hayman Fire in 2002, Colorado had never had a fire in recorded history that exceeded 100,000 acres. But the state mourned a dark milestone in summer 2020, when the Cameron Peak Fire burned 200,000 acres, an area bigger than New York City.

Incredibly, all 20 of Colorado’s largest wildfires have happened in the last 20 years.

Fire season now lasts longer, too. A few decades ago, a wildfire in a Boulder suburb would have been hard to fathom, and a wildfire in a Boulder suburb in late December would have been nearly unthinkable. But the Marshall Fire had it made easy: near-record-setting heat and drought parched Colorado’s Front Range in 2021. From June to December, Boulder typically gets 30 inches of snow; during that period in 2021, it got a single inch.

What is most troubling is how scientists’ most dire predictions are coming true. In 2019, Dr. Mahood and his colleagues decided to use statistical modeling to gauge the chances of a million-acre fire—a fire of such staggering size, Dr. Mahood says, that the calculation was mostly “a thought experiment.” But the probability was higher than they expected, so they mentioned it in a paper published in 2019. The likelihood of a million-acre fire in the US, the paper reads, is “non-negligible.”

The next year, the million-acre August Complex fire scorched California, a first in the state’s history.

Despite all of this, Colorado’s oil and gas industry—the industry most at fault for the emissions damaging the climate—is tightening its stranglehold on the state’s economy by pouring money into politics, disinformation campaigns, and unscientific “research.” As my colleague Ortal Ullman writes, “Money speaks, and the fossil fuel industry is holding a megaphone.”

Scientists’ work and life collide

For many fire and climate researchers, work hits close to home.

“Before I leave the house, I have to check the air quality,” says Dr. Mahood, who lives in Boulder. Cities like Boulder rub elbows with wilderness, leaving no buffer. “If I accidentally go for a run when the air quality is poor, I’ll cough for half an hour afterward.”

“And if a fire happens here,” he says, “I’ll be running for my life.”

Some of his colleagues, who have already lost homes in wildfires, know exactly what he means.

Dr. Fassnacht, the snow hydrologist, remembers sweeping ash off his patio during the 2012 and 2020 wildfires. He commuted to campus wearing an N95 mask, worried about the smoke. Worse still, he says, was visiting his favorite trails after the fire—including the Cirque Meadows Trail, a picturesque hike through the foothills. The Cameron Peak Fire ripped through the area, leaving burned trees and bare hillside in its wake.

“I had been up and down that trail for 15 years,” he said. “It’s devastating.”

Dr. Kristina Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and a resident of San Francisco, has watched the skies turn orange during California’s worst fires. “For days, my kids had to stay inside because of the smoke,” she said. Witnessing the damage to the great forests of Yosemite, a few hours’ drive away, has been “heartbreaking,” she says.

Colorado’s wildfires hit too close to home

It’s personal for me, too.

In 2012, my family evacuated during Colorado’s High Park Fire. As we frantically packed up, my 6-year-old brother Merrick insisted we take his Hot Wheels collection. But we didn’t have room in the car, not with the heirlooms, suitcases, photo albums, sleeping bags, pillows, the terrified cat in her carrier, the dog, the guinea pig, and seven panicked humans. So, as we pulled down the driveway in the pre-dawn darkness with only some of his toys, my brother sobbed.

From my grandparents’ house 20 miles away, we watched the smoke rise from the foothills. For weeks, we heard the thrum of helicopters, which doused the fire with huge bucketfuls of water. We studied footage of planes spraying clouds of flame retardant, staining the earth red.

In the end, my family was lucky. The flames came within 1,000 feet of our neighborhood, but firefighters fought it off. We returned home a few weeks later; Merrick’s toys survived their ordeal.

Still, the High Park fire gulped almost 90,000 acres down its maw. It burned nearly 250 houses, including the home of my history teacher. And if you drive up into the foothills, you’ll eventually pass a home on Old Flowers Road, where a 62-year-old woman died during the fire.

A decade later, scars remain. Behind my family’s neighborhood, on the tops of the foothills that roll west, black trees loom, charred remnants of the fire.

You may not live in Colorado, or even the West. Perhaps these seem like only distant threats. But all of us are leading characters in the story of climate change, the actors as much as the playwrights.

It’s up to us to decide what comes next—and the clock is ticking.

“These fires will get worse,” says Dr. Dahl. “We’re running out of time.”

Dr. Mahood used starker terms.

“This is a global emergency,” he said. “And in an emergency, you don’t stand around thinking about what makes you hopeful.”

Instead, he says, you do something about it.

_____

To learn more about what the Union of Concerned Scientists is doing to act on the climate crisis, and to learn what you can do to help, please click here.

To read UCS’s reports and articles on Colorado’s battle with climate change—and the behemoth industries fueling it—see here, here, here, and here.