Black History Month, for me, has always been a time to celebrate Black people, and our contributions to society. As a first-generation American, I’m also reflecting on and grateful for the avenues that were made available for my parents when they emigrated to the United States in the late 1980s: Black people in America made it possible for them to come and seek opportunities. As a Black scientist, it’s especially important to me to acknowledge and celebrate Black scientists and activists who made major contributions to all fields of science despite the barriers of systemic and structural racism. Black scientists paved the way for me to be able to become a scientist, and have inspired me to work towards creating a more inclusive space for all of us.

I used to work in the biosecurity and biodefense world, where I worked to assess federal laboratory safety and methods to ensure that dangerous pathogens that are stored for research wouldn’t get into the hands of people who might want to use them to create biological weapons. Not only did this field lack diversity across the board, there was little opportunity to engage and inform the public. We often thought about the possibilities of biological warfare and the means one could use to execute it, but I was always thinking: if something like that were to happen, how can we make safety and resilience measures more considerate of already vulnerable populations? How can we communicate this risk in a way that most people who don’t read scientific jargon for a living can digest it? I was often alone in this thinking, and felt solely responsible for these considerations (which were usually ignored). Colleagues would ask, “Why would the safety of a few populations matter when pathogens can infect all humans?” While not a case of biological warfare, we saw the answer to this question during the COVID-19 pandemic where we saw limited access to healthcare, issues with distributing personal protective gear, and the disproportionate infection and mortality rates of Black people.

As we continue to make scientific advances and strides toward a more inclusive academia and America at large, this Black History Month I wanted to share a few things we can all reflect on this month, and beyond.

There are legends around us

Every February, since my first taste of science in grade school (shoutout to the Baltimore City Public School System), I have taken the time to remember and celebrate Black people in American history. I’m so grateful that I attended school in a district that valued Black history programming and critical race theory. Some of my earliest heroes were scientists and technical experts who have made notable achievements in our fields through theories, inventions, discoveries, and advocacy for the disenfranchised. I remember learning about George Washington Carver and the contributions he made to agriculture and improving crop yields for Black farmers. I later learned about Percy Julian, the organic chemist who contributed to medicine by synthesizing progesterone and cortisone (two important hormones in the human body) from natural products.

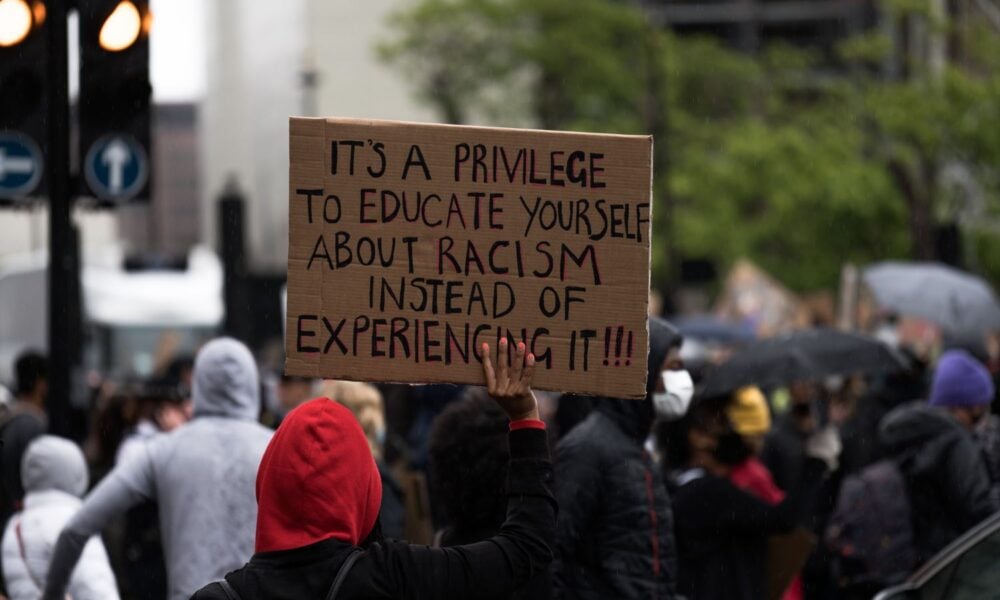

I also take time to reflect on the accomplished around us: our colleagues, mentors, mentees, and thought leaders and partners. They are living and accessible examples of how far we’ve come, and they are holders of the stories illustrating how far we still need to go. Tangible accomplishments deserve recognition, but it is important to also acknowledge that organizing, educating, and inspiring people to push for change is an equally important and often overlooked contribution to society. Seeing scientists alongside activists fighting for a safer world made me want to explore ways that I could also help effect change.

The plight of Black excellence

Despite the many amazing Black scientists and activists doing awesome work today, it’s still harder than it should be for Black people to become scientists and thrive in academia and other institutions. Black students need to see people who look like them in scientific spaces. Keisha Hardeman, a postdoc at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, succinctly describes an experience that I resonated with deeply: “It was only when I started college at a predominantly white institution that I began to question whether I was a fool for thinking someone like me could be a scientist. I was usually the only Black student in my classes, and I had no Black professors.”

I had a similar experience: I attended predominantly Black schools for K-12, and attended PWIs (predominantly white institutions) for both my bachelor’s and master’s programs. While I could have guessed what it would feel like to be the only Black student in many of my classes, nothing could have prepared me for the stark difference in support, encouragement, and overall experience. Aside from the lack of representation in academia and scientific spaces broadly, simply being Black in predominantly white spaces comes with microaggressions and unfair treatment. From situations that may not seem worth correcting (like mispronunciation, misspelling or complete omission of our names from major projects and acknowledgements) to discrimination in award and fellowship selections, Black scientists have a unique and often negative experience. Hardeman continues in saying, “The scientific challenges I encounter are nowhere near as discouraging as the systemic racism I’ve encountered in academia.” They describe the deterioration of their own mental health, as well as two peers who “died of suicide as a result of working in toxic environments.” In the more recent quest for institutions to become more inclusive, it is not enough to simply hire more Black people. Materials engineer Dante O’Hara writes, “Institutions that cause harm through racist and class exploitative policy avoid making substantive policy changes using ‘diversity and inclusion’ as a shield.”

While it is great to see more Black scientists graduating and leading in research, tokenization of Black people and exploitation of our emotional labor to justify our presence in scientific spaces is further perpetuating structural and systemic racism. We’ve made progress, but the road ahead is long.

Science is inherently a justice and trust issue

Issues that affect all Americans, like air/ground/water pollution, healthy food access, and the many effects of climate change, disproportionately impact Black communities. This is compounded by racism that exists in the healthcare system and in medical research that people rely on to understand and treat ailments likely caused by these inequities. There is a distrust of scientists and medical researchers when it comes to addressing our public health needs (understandably). While science is thought of by many of our peers as “objective” and “non-political,” it is important for us to see that science has been (and still is) used to perpetuate injustice and harm to Black communities throughout American history. Black people have been subject to prejudice and cruelty at the hands of scientific research, one notable example being the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Science has been used for many years to justify racist assumptions about the correlations between crime, education, and poverty in Black communities, and to support discrimination and unjust treatment of Black people through medical experimentation and racial profiling. As recently as 1992, experiments were performed on 126 Black boys (aged 6-10, who were younger siblings of juvenile offenders in NYC) in a study that aimed to find a link between genetics and violence. The boys were withdrawn from all their routine medications, placed on a low-protein diet, and given fenfluramine (a seizure medication not previously used in patients under 12 years of age, and later pulled from the market after it was found to cause heart valve disease).

Science has also been used to support the placement of pollution-promoting structures such as major highways, Superfund sites, waste processing plants, power plants, toxic waste sites, and uranium mining sites–all of which are often placed in communities where Black people are part of the majority. We know that these environmental harms contribute to increased health risks and a less habitable environment for the people living in vicinity of them.

Lack of representation causes a limited understanding of the needs and concerns of Black people. Science, when not informed by inclusive perspectives, takes an empirical approach, creating distance from the problem. Observing vulnerable populations by collecting mostly quantitative data also allows us to distance our thinking from the problem. It is important to center humanity and the Black lived experience to effectively advocate for Black communities. The Black experience is not a monolith, and the way in which we collect data affects the ultimate outcome: how we use science to positively affect the lives of the people in the African diaspora.

Lived experience is expertise

While uplifting and celebrating the Black scientists and experts who move among us, we must also remember that lived experience is a unique type of expertise that can’t be replicated in a classroom, laboratory, or listening space. Black scientists possess this type of expertise, and it is important to remember we are all supported by people who are not scientists in the traditional sense. The letters after our names reflect just one form of expertise, and I recognize and respect the many other valid ways that my Black peers and loved ones—and I—are experts in our own lives and challenges. As we advocate for ourselves, the environment, and overall a safer and healthier planet for all, we do this on the shoulders of many. Collaborations in our communities have taken us far and will continue to take us further as long as we acknowledge those who uplift and support us.

For our peers, in contribution to the greater good, we humanize the issues, tell stories, and make the issues our own.

It’s all connected

In order to effectively advocate for Black people (and people in general), we all need to both encourage inclusivity and promote a culture that supports, respects, and uplifts ALL Black people (not just our friends, those adjacent to us, and people whose accomplishments have deemed them “worthy” of respect in our society). It should not take another tragedy to remind people that we are worthy of respect and safety in our communities. As scientist-advocates we understand that history is made every day by having a commitment to change and action to do it.

When it comes to Black History Month, ask yourself: what is my commitment? What is my action to contribute to change? How do I ensure that I am considering the underrepresented and disenfranchised in my work for the greater good? How do I uplift my Black peers and their voices when we fight for issues that affect our communities the most?

You don’t have to have all the answers to begin thinking about how to apply these values to your work and beyond. Learn from the people most impacted. Learn from those who are already doing the work as advocates and activists. Whether it’s taking action for racial justice within your institutions, supporting your colleagues and peers who are taking a principled stand, or advocating for equitable policy solutions, there are a hundred ways to start putting your values into action.