With the clean energy transition already under way, the US electricity mix is set to continue changing this year. The general outlook includes some good news and some bad news. I’ll start off with the good.

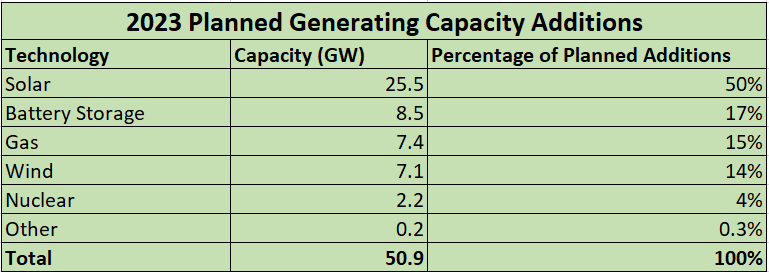

Solar power is expected to make up about half of all additions of US electric generating capacity in 2023, according to data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The 25.5 gigawatts (GW) of planned solar projects expected to come online this year is almost double the previous 13.4 GW record from 2021. Further, this estimate doesn’t even include smaller-scale projects such as rooftop solar, additions of which are also expected to be significant.

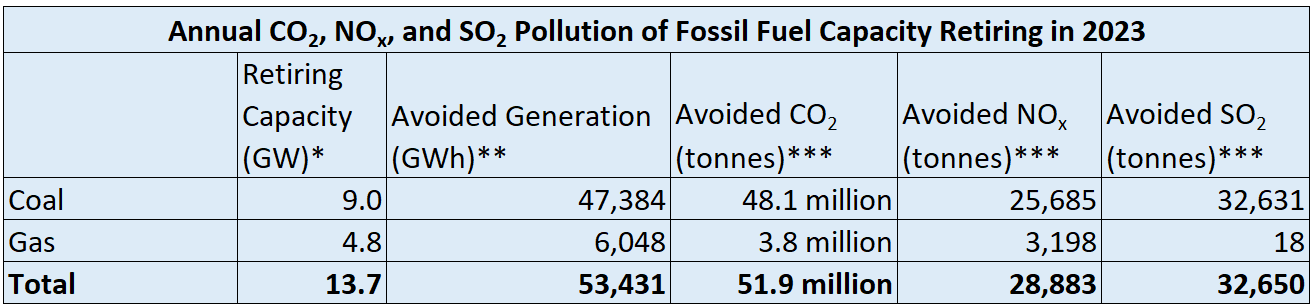

The addition of newer, cleaner resources like solar power to our electricity grid will happen in tandem with the planned retirement (or permanent closure) of older and dirtier resources such as coal- and gas-fired power plants, which make up 98 percent of the planned retirements in 2023.

However, there’s uncertainty about how much of this additional capacity will come to fruition this year. Renewable projects can experience delays due to the country’s antiquated (and slow) system of connecting to the grid, as well as other reasons like permitting and transmission constraints. And fossil fuel power plants may not stick to their retirement schedules for a variety of reasons. A bit more on those reasons later.

But if plant owners actually do follow through on their retirement plans, there will be real, tangible public health and environmental benefits. In 2021 alone, the plants slated for retirement emitted more than 28,000 tonnes of nitrogen oxides (NOx), 32,000 tonnes of sulfur dioxide (SO2), and 51 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), according to EIA data.

Here’s why that matters: In addition to environmental effects—like reduced visibility due to haze—NOx and SO2 emissions both contribute to extremely small particles called particulate matter (PM) pollution, which has been linked to a wide array of human health impacts including reduced lung function, heart attacks, and premature deaths of people with heart or lung disease. NOx also contributes to the formation of ozone (or “smog”), another toxic pollutant.

A recent study found that more than 99 percent of the global population is exposed to unsafe levels of PM2.5 pollution, which are particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometers or less. In 2019, air pollution more broadly was responsible for about 6.7 million deaths globally.

And CO2 emissions are a primary driver of global climate change, which is exacerbating the type of extreme weather that killed 474 people and caused $165 billion in damages in the United States last year alone. So what might happen if all the plants that are scheduled to retire did in fact retire and never burned fuel again?

Health and environmental damages avoided

Using Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates, the United States could avoid more than $18 billion in annual damages from CO2, NOx, and SO2 if all the coal and gas plants scheduled for retirement in 2023 permanently shut down as planned.

(Note: this is adjusted for inflation to 2022 dollars and is based on the amount those plants emitted in 2021, the EIA’s most recent year of finalized data. The EPA’s Social Cost of Carbon was adjusted to 2025 to align with the emissions year of the NOx and SO2 estimates.)

Keep in mind that this calculation comes nowhere close to a full estimation of the costs that would be avoided by retiring these power plants, since it only focuses on three pollutants and doesn’t account for the effects taking place upstream of the plants, such as the health and environmental impacts of extracting gas and coal. Moreover, analysts generally consider EIA data to be relatively conservative, so the plant closures and associated benefits could potentially be even greater this year, especially now that 99 percent of existing US coal plants are more expensive to run than building new wind and solar generating capacity, according to a recent analysis.

This transition away from coal can be done while also addressing the associated negative impacts, such as lost jobs and reduced tax bases for communities. The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) found in a 2021 report with the Utility Workers Union of America that supporting former US coal industry workers through the clean energy transition can be achieved affordably with adequate planning, funding, and stakeholder engagement.

Overall, the planned closure of these fossil fuel power plants is good news for the global climate and the health of surrounding communities—which tend to be communities of color—that have had to endure decades of air and water pollution from those facilities.

Unfortunately, the outlook isn’t a 100 percent good-news story for a few different reasons. First, there are even more gas plants planned to come online this year. Further, not all the health and environmental benefits from plant retirements are guaranteed. And finally, even if all the fossil plants retire as scheduled, the pace is still not quick enough to get the country on track to meet its clean energy goals.

More gas plants, uncertain coal retirements

As you may have noticed in the first table toward the top of the page, about 7.4 GW of new gas capacity is planned to come online in 2023, outpacing not only the 4.8 GW of gas capacity set to retire, but also slightly outpacing the planned additions of wind power.

These new gas plants, which are not clean, could also potentially generate roughly five times the amount of electricity that the retiring gas plants generated in 2021. This is because more than 80 percent of the new gas-fired capacity coming online will use so-called combined-cycle technology that, because of its comparatively greater efficiency, typically results in plants running more frequently compared with older steam turbines, which make up about 78 percent of the gas-fired capacity set to retire this year.

And while gas plants emit little SO2, the additional emissions from this new gas-fired capacity could undo about 24 percent of the CO2 emissions reductions and nearly all—more than 98 percent—of the NOx emissions reductions resulting from the planned coal and gas retirements.

The bottom line: There’s still a long way to go, and the clean energy transition must move quicker than it has been—despite the fossil fuel industry’s self-serving claims to the contrary.

Modeling has shown that if the United States is going to live up to its Paris Agreement targets aimed at limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, coal power should be entirely phased out by 2030.

Yet none of the country’s 10 most-polluting coal plants are set to retire this year, and many of them are currently scheduled to continue running well into the 2030s. US coal plants that are neither economic nor compliant with federal environmental regulations are being kept online well past their profitable lives due to both political reasons and assertions of about grid reliability concerns that, in reality, could be addressed with cleaner and cheaper technologies.

What can be done?

With all that said, there are many ways policymakers at virtually every level of government can bring more certainty and speed to the retirement of fossil fuel power plants and the installation of clean energy capacity to replace them. In doing so, the country can start realizing more of the tremendous economic, health, and environmental benefits of a clean energy future, while not leaving communities behind in the transition.

Federal policymakers should continue breaking down market barriers for clean energy resources, while also going beyond the existing policy efforts to facilitate the buildout of a modern transmission grid that can transport more renewable electricity. State regulators should thoroughly scrutinize any utility company plans that would invest in new fossil fuel power plants or keep existing ones online at ratepayers’ expense, particularly now that tax incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) have made cleaner resources like wind, solar, and energy storage even more cost-effective than before.

Alongside federal and state government entities, communities should also take advantage of the wide array of incentives for local governments provisioned by the IRA, which, among other things, earmarks billions of dollars in funding for clean energy projects in communities with closed coal mines or plants.

The transition away from a fossil fuel power system to a clean electricity grid is achievable, but policymakers must use their existing tools more expeditiously and continue adding more tools, as UCS has been pushing—and will continue pushing—them to do.