On March 20, 1990, the Unit 1 reactor at the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia was shut down during a refueling outage. A worker accompanied by a security guard drove a fuel truck into the plant’s electrical switchyard to refill a welding machine. The security guard went along to ensure that neither the worker nor the vehicle, if driven by another individual, sabotaged the plant.

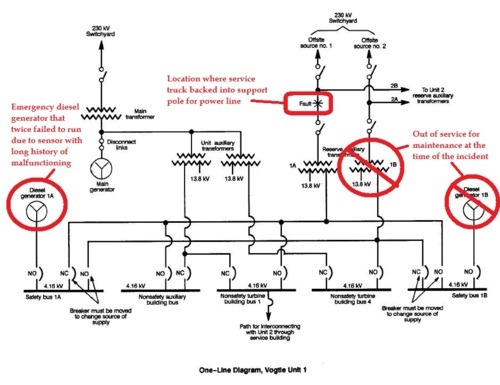

The security guard may not have fully understood this role. In any case, the worker found that the welding machine did not need fuel. Backing up the service truck while turning around to exit the switchyard, he accidentally drove into a support pole for a 230,000 volt overhead transmission line. The impact caused an electrical fault that de-energized Reserve Auxiliary Transformer 1A, the only transformer linking Unit 1 to the offsite electrical power grid. Unit 1 experienced a loss of offsite power (known as LOOP).Emergency diesel generator 1B was out of service for maintenance at the time. The other only emergency diesel generator (EDG) automatically started, but stopped running 70 seconds later. A sensor on the EDG’s cooling system malfunctioned, causing the EDG to stop running. This sensor had failed 69 times since 1985, or roughly once a month leading up to this incident, but had never been fixed.

With the EDGs unavailable during the LOOP, Vogtle Unit 1 experienced a station blackout – the total loss of all AC power. The only electrical equipment functioning on the unit was powered from the station’s batteries. The Figure below shows a schematic of the electrical distribution system for Vogtle Unit 1.

Repairs to the diesel generator were complicated because all the lights in the diesel generator building were disabled by the loss of electrical power. Operators manually restarted the diesel generator about 18 minutes into the event, but it tripped again after running for about a minute. Operators started the diesel generator a third time in an emergency mode and re-supplied power to safety equipment 36 minutes after the blackout began. The temperature of the reactor’s cooling water rose from 90°F to 136°F during the power outage.

The plant’s owners declared an Alert, the second lowest of the NRC’s four emergency classifications as a result of the loss of power and its challenge to reactor core cooling. The Alert declaration required that all personnel at the plant to be accounted for within 30 minutes. An hour after the emergency was declared, 120 people were still unaccounted for. Four hours after the Alert, there were still 49 people unaccounted for. It is believed that all workers have now been located although the NRC report is not clear on this point.

Our Takeaway

The station blackout at Vogtle happened despite many intentional and conditional barriers that could have, and should have, prevented it:

- A security guard whose only job was to prevent one worker and one vehicle from causing harm to the plant watched that worker ram that truck into a power pole in the switchyard.

- That worker drove the truck into the switchyard to refuel a welding machine that did not need refueled.

- The only available EDG failed to run, twice, due to a malfunctioning part that had tolerated for years.

As bad as the situation was, it could have been more severe if electrical arcing had ignited the fuel in the truck. Additional damage that could have resulted from a fire or explosion would have further complicated recovery from the incident.

The recent disaster at Fukushima Dai-Ichi was primarily caused by a station blackout lasting longer than expected. At some U.S. reactors, the risk of reactor meltdown from station blackout is greater than the risk from all other possible causes combined. It is a real risk that demands real attention in order to prevent real disasters.

Sad Footnote

Allen Mosbaugh, a manager at the Vogtle plant, told the NRC about alleged falsification of EDG tests. Due to the EDG’s failures during the event, the NRC had required a series of successful EDG tests to be completed before the unit could restart. In order to compile the required number of successful tests in a row, Mosbaugh informed the NRC that a senior manager directed workers to exclude several test failures and only include successful tests. The plant’s owners fired Mosbaugh.

The NRC conducted a long, intensive investigation into his firing. They determined that the firing violated federal regulations. The NRC cited the plant’s owners for a Severity I, or most serious, violation. The NRC indicated that it also wanted to fine the company $100,000 for this deliberate violation by a senior company official, but could not because the five year statute of limitations that began when the test records were “doctored” had expired just days earlier. They say Justice is blind. That might explain why Justice was unable to read a calendar and appropriately sanction this wrong-doer.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.