The summer of 2012 officially ended last week, but not before showing the United States the many ways it’s vulnerable to heat and drought, and ill-prepared for our warming future. Not least among these, we saw how our power sector strained under the kind of searing summer conditions our mid-century selves may find commonplace. Our electricity system, it turns out, wasn’t built for summers like 2012, and it showed.

At UCS, we’ve been thinking about electricity-water “collisions” the past couple of years — those instances when our power sector’s dependence on water creates problems — either for the power plant or the water body.

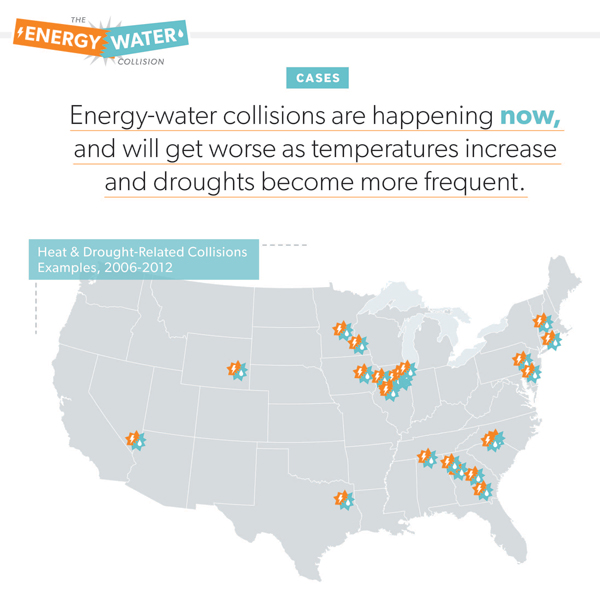

In late June, we finalized a new infographic that described the specific threats to power plants during hot, dry summers, and provided a list of recent examples from around the country of these threats manifesting. Heat and drought were settling in at that point and some power plants were beginning to have difficulty securing sufficient cooling water. By late July, there were already half a dozen new examples to add to the list, with more still coming in by the end of the summer.

If you can’t take the heat, get on this map

This week, we’ve released an updated infographic, with additional cases of “collisions” added to the map. See the full infographic for a list of plants involved; we’ve found plenty of new ones, and there are still more to identify.

All of the new 2012 cases help shed light on how dependent our electricity system is on an adequate water supply, but some really showcase how far this summer went in amplifying existing risks and exposing new ones:

- Vermont Yankee: In the first such case we’ve found in northern New England, the Vermont Yankee nuclear plant was forced to reduce its power production over the course of a week by as much as 17 percent because of high water temperatures and low flow in the Connecticut River.

- Millstone nuclear plant: In the case of Millstone, it was Long Island Sound that got too warm, forcing the plant to shut down one of its two reactors for 11 days in mid-July. This represents the first open-water case that we’re aware of and signals that even plants on large bodies of water are at risk as temperatures increase.

- Illinois: A rash of coal and nuclear plants sought and received from the state “thermal variances” to let them to discharge hotter water than their permits allow, even amidst extensive heat-related fish kills.

Taking the Heartland experience to heart

We have so much to learn from this summer. But I want to spend a minute on this last case, which is as interesting as it is troubling. The Midwest was sweltering, water temperatures were soaring, and fish were dying, perhaps by the millions.

In Illinois, when power plants began to run into trouble and to seek permission to discharge even hotter water, it seemed at first like the well-being of fish populations would need to be weighed against that of the human population — which needed reliable electricity for air conditioning. As a spokeswoman for Midwest Generation put it “Do you want people to start dying, or do you want to save some fish?” In that kind of tradeoff, the power is going to be supplied and fish are going to lose.

Illinois’ Braidwood nuclear plant, pictured here, was one of eight coal and nuclear plants to receive state permission this summer to release hotter water than normally allowed. (Photo credit: NRCgov)

But are those the choices? In recent years, operators of some of these same plants had opted to dial back power production to cope with warm incoming water and the risk of violating discharge permits. In 2012, though, the utilities instead sought permission from the state to exceed their temperature limits and to keep running at full power.

As the Chicago Tribune coverage notes, the utilities claim that their continued operation was essential to keep the power on rang hollow to some, in a state that exports power. Nevertheless, even as fish kills mounted and the region tallied tens of millions of dollars in fisheries-related losses, these plants were able to discharge hotter-than-normal water into Illinois’ hotter-than-normal water bodies.

In another twist, as their source for cooling water heats up, power plants become less efficient, requiring more water from that source in order to achieve the same level of cooling and produce the same level of electricity. This would suggest that, in places like Illinois this summer, not only could these plants discharge hotter water, but they could heat greater volumes of water than normal.

If you can’t take the heat, get out of the future

The trouble with this outcome is that, with more hot, dry summers on tap for the Midwest and much of the nation, one can imagine that thirsty coal and nuclear plants would require thermal variances ever more often to keep operating in those conditions — further stressing lakes, rivers, wildlife, and the millions of people who care about and count on these.

In the Southeast, the Oconee River is on tap as the cooling-water source for a new coal-fired plant. But local groups say that if Plant Washington had been operational during this drought, it would have had to repeatedly resort to its back-up cooling-water source: groundwater. (Photo credit: Courtney McGough)

I can understand how we got here, but I can’t understand continuing down this road when it clearly doesn’t lead to a resilient energy future. We can do better.

To see this summer’s energy-water collisions most clearly — and to start to imagine a collision-free future — it’ll be useful to look at the kinds of plants that aren’t on this map: some because they don’t rely on water, others because they’re trying hard not to be too heavily-reliant, and some — though they were impacted during this summer’s heat and drought — because there just isn’t enough information being released about them.

That’s up next. Please stay tuned.