In late December, the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) released proposed regulations for the Section 45V Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit. The tax credit, passed as part of 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act, provides a generous incentive for the production of clean hydrogen.

Today, hydrogen is overwhelmingly produced through a heavily polluting fossil fuel-based process. It is a climate problem, not a climate solution. But hydrogen can be cleanly produced and, with the right guardrails in place, that clean hydrogen can then be used to clean up polluting parts of the economy that can’t readily convert to running on renewable electricity. That makes hydrogen a valuable tool for targeted use in the clean energy transition—but again, only if it’s cleanly produced. Otherwise, hydrogen will slow the clean energy transition, not speed it.

However, verifying that hydrogen is produced in a low-carbon way can be complicated, especially for electrolytically produced hydrogen, where electricity is used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

Fortunately, the proposed regulations for implementing 45V demonstrate a recognition of that challenge and a ready and robust approach for overcoming it by adopting electrolyzer clean energy procurement requirements of incrementality, geographic deliverability, and time matching (i.e., the “three pillars”). Even with this strong starting framework, a series of outstanding issues could seriously undermine the integrity of the otherwise-robust approach. Finding careful resolution to these issues will be a key point of focus over the comment period for these regulations, which is set to run through February 26th, 2024.

Here’s a breakdown of the top three things to know related to Treasury’s treatment of electrolytically produced hydrogen. The proposed regulation’s treatment of hydrogen produced via methane, including through use of biomethane and fugitive methane, is covered in a separate post.

1. Treasury established a rigorous framework—and brought the receipts

When the proposed 45V implementation guidance was released in December, it was immediately clear that the administration had invested significant time doing deep work. The proposed regulations outline a rigorous approach to establishing eligible “clean hydrogen” production, coupled with a detailed preamble laying out the administration’s reasoning, motivation, and intent.

The release also included multiple supporting resources.

Foremost among these is a legal memo from EPA regarding Treasury’s interpretation and implementation of “lifecycle greenhouse-gas emissions” in 45V. Though seemingly obscure, this memo is fundamental to justifying Treasury’s proposed three-pillars approach. That’s because 45V awards credits based on the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions rate of produced hydrogen, and the statutory text defines that term via explicit reference to a definition set in the Clean Air Act. Critically, the definition requires considering direct emissions and “significant indirect emissions,” and EPA’s legal memo carefully steps through why accounting for induced grid emissions, i.e., carbon emissions that result from coal and gas plants ramping up operations to meet increased electricity demand by electrolyzers in the absence of pollution guardrails, is the correct legal interpretation.

In so doing, EPA not only affirms Treasury’s approach but underscores its necessity.

EPA’s legal memo also affirms the reasonableness of Treasury’s proposed use of three pillars-compliant Energy Attribute Certificates (EACs) as a proxy for ensuring no induced grid emissions, thereby enabling electrolyzer projects to qualify for the highest-credit tier.

Additionally, the Department of Energy (DOE) released a white paper detailing the lifecycle carbon emissions from electrolyzer operations, the enormity of grid-wide emission increases that could result without requirements specifically tailored to approximate and limit those effects, and how use of three pillars-compliant EACs could be a reasonable approach for zeroing out induced grid emissions for the purposes of lifecycle emissions accounting.

Finally, the administration released a 45V-specific iteration of the GREET model, a lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions analysis tool, as well as an accompanying user guide, which together enable hydrogen producers to evaluate the emissions rate of their projects and thus determine the credit tier for which their produced hydrogen is eligible.

The one place where the record remains thin? Issues around biomethane and fugitive methane. The administration is transparent on this front, though, filling the proposal with questions aimed at resource identification to enable rigorous issue resolution.

2. For electrolytic pathways, the three pillars set the frame…

Electrolysis is an energy-intensive process. If electrolyzers simply plug into the existing electricity system with no safeguards in place, grid-wide emissions are likely to spike. That’s because renewables are already running full-out, meaning only coal and gas plants can ramp up to meet the sudden increase in electricity demand. Rigorous requirements to protect against such outcomes are therefore critical; otherwise, the country would be pouring billions of dollars into a tax credit intended to support the clean energy transition that would instead ultimately increase our overall carbon emissions. Not great.

Critically, the proposed regulations recognize this problem and put forward exactly the guardrails needed to protect against it. Specifically, hydrogen producers running electrolyzers must acquire and retire certificates for clean resources that meet the following three criteria:

- Incrementality. Also sometimes referred to as “additionality,” this sets the requirement for how to verify procured clean energy is coming from new sources—not just diverting those already on the system and currently being consumed by others. To be eligible, clean resources must begin commercial operations within 36 months of a hydrogen production facility being placed into service. Additional allowances are made for uprates at existing facilities.

- Geographic deliverability. To ensure the clean resources procured by a hydrogen producer are actually able to be consumed by that producer—and not instead met by local fossil fuel plants due to transmission constraints between the producer and consumer—the regulations require that procured resources must be located within the same region as the electrolyzer, as determined via DOE’s recent National Transmission Needs Study.

- Time matching. Recognizing that there could be a temporal mismatch between clean energy production and periods of electrolyzer operations—a gap likely to be filled by fossil-fuel resources—the regulations require that procured clean resources are matched on an hourly basis with electrolyzer operations. However, to enable scaling up of the systems required for such hourly matching, producers can rely on annual matching until 2028, at which time all producers—new and existing—must convert to hourly matching.

3. …But loopholes lurk

For as strong as the proposed electrolytic framework is, it’s critical to note that multiple potential loopholes remain outstanding. Depending on their resolution, these issues could either be reasonably handled to accommodate particular realities about the grid and necessary implementation flexibilities, or they could function as wholesale workarounds for the rigor set out by the three pillars, thereby entirely undermining the integrity of the framework. Two such issues rise to the fore:

- Exceptions for use of existing clean resources. Requiring procurement of new clean resources is fundamental to protecting against a diversion of existing clean resources instead. However, there are circumstances where existing clean resources are underutilized, and if hydrogen producers can take advantage of those periods, that generation should indeed be eligible as “new” clean energy. But these are typically geographically specific, in the case of curtailments, or plant-by-plant specific, in the case of pending retirements or relicensing, or state specific, in the face of pre-existing policies that defend against system-wide emissions increases.

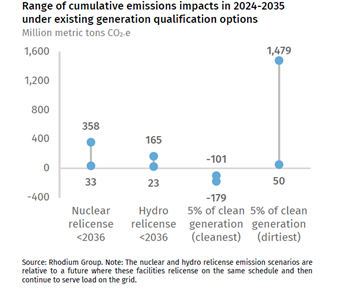

If Treasury were to depart from a necessarily tailored approach for any of these issues and instead allow for a generalized proxy, such as allowing 5 or 10 percent of all existing clean generation to count as eligible—a scenario that Treasury has floated for consideration—it could have staggering emissions ramifications. Rhodium Group undertook an initial analysis of this issue and helped illustrate what’s at stake, ranging from enabling additional emissions reductions if carefully tailored, to sending emissions soaring by well over one billion metric tons if not.

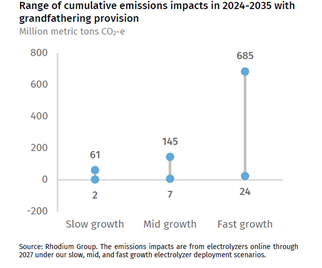

- Weakening or delaying the shift to hourly matching. The proposed regulations require a shift to hourly matching for all hydrogen producers in 2028—including those operating before that date who are allowed to use annual matching in the interim. Some potential hydrogen producers have called for delaying the year in which the switch to hourly matching is made, while others have called for allowing “legacy” producers who come online during the early annual-matching phase-in period to never be required to make the shift to hourly matching. Notably, while allowing these legacy producers to operate under different rules could seem like a small compromise, it could in fact result in significant emissions increases. Again, Rhodium Group considered such a scenario, finding emissions could increase by 145 million metric tons in a mid-electrolyzer-growth scenario, or by 685 million metric tons in a fast-growth scenario.

These are by no means the only parts of the regulations that could lead to increased emissions from electrolytic pathways based on rule finalization; the proposed guidance raises numerous issues for comment that could, if weakly finalized, moderately to substantially undermine the integrity of the rule. The above two, however, are a central part of the ongoing debate and at greatest risk of actualizing loopholes that would have enormous and cascading pollution effects.

What comes next

The proposed regulations are open for comment through February 26th, with a public hearing scheduled for March 25th. Protecting against backsliding will be key. Treasury proposed a necessarily rigorous approach to accounting for emissions from electrolytic hydrogen production and it cannot back away from that. Moreover, any flexibilities allowed around the main framework must be carefully tailored; otherwise, the carbon pollution implications could be severe—while wasting hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars.

But preventing backsliding will be hard.

From the jump, a segment of the nascent hydrogen industry, alongside the fossil fuel industry, has been howling about any semblance of rigorous standards that could curtail their ability to deploy projects without consideration of their true emissions impact. They are also mobilizing members of Congress who should know better by threatening that rigorous standards will result in the failing of Hydrogen Hub projects.

These voices should not be so readily believed. Unsurprisingly, those objecting are the segment of the hydrogen industry looking to make an easy profit without any thought to whether or how their business plans align with the clean energy transition. By contrast, those industry players specifically making a play for business viability in a climate-aligned environment are endorsing the proposed regulations; these are the voices one should be looking toward.

Investing in the clean energy transition means investing in projects that are truly climate-aligned. Treasury took the right first step, exactly as the Inflation Reduction Act intended; it can’t backslide now.