At some point as a bright-eyed kid who loved STEM, I was told to “draw an engineer”. You can probably guess what happened. My little stick figure came with a hard hat, a wrench, and no indication of them being a woman. This matches over 50 years of research showing children drawing only 27% of scientists as female, with similar trends for drawing engineers. And when children don’t imagine women as engineers and scientists, that directly shapes the future. This already shows up with severe underrepresentation of women in civil engineering (16%) and the transportation industry as a whole (14.5%).

And this is just the tip of the iceberg of the many ways sexism pervades transportation. As someone who identifies as a man, I first encourage you to hear from women leaders in the field directly on this, such as Veronica Davis and tamika l. butler, members of TransitCenter’s Women Changing Transportation program, and the women at UCS and our Science Network. These people truly embody the strong and courageous spirit of this quote by Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa:

“Caminante, no hay puentes, se hacen puentes al andar”

(Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks)

Please mind the (gender) gap

We all rely on transportation to get to where we need to go, and the lack of diversity in the industry and among decisionmakers leads to a world designed for men. Across all parts of the transportation system, this has particular consequences for women.

Let’s start on the sidewalk. One study found that women were more concerned about traffic safety factors such as the presence of street lighting and automobile speeds when deciding whether to walk, and are limited by the lack of such infrastructure. This also shows itself in the gender gap in bicycling – women ride bikes around three times less than men in the US, which researchers have attributed to the lack of safe infrastructure, which affects women’s travel behavior more, but in the end, safer infrastructure would protect all of us.

Personal safety is also an obvious one—it can be challenging to be a woman in public space. This ranges from cat calls and intimidation to the most severe violence and sexual harassment from men. Low-income women and women of color are hit hardest, given they are more likely to be returning from work in late evening hours or have less private transportation options. A study in 2022 showed that 79 of 129 US transit agencies assessed had little to no mention of gender or gender equity on their agency materials. So, while there are many noted concerns, little has been done to address them in practice.

Care work – such as grocery shopping, dropping and picking up kids from school, and chauffeuring other dependents–is also placed disproportionately on women. Globally, women spend an average of four and a half hours a day on this, more than double the time men spend. As a result, women are more likely to “trip chain”, or take an extra stop for these tasks on the way to work or home. Public transit systems, on the other hand, for decades have been built for a nine-to-five rush hour commute straight to and from work (think commuter rail, which prioritizes one long commute trip rather than any stops along the way).

Those difficulties can push women even more towards driving a car, but even there, gender makes a difference. Despite the fact that female drivers make up more than half of all licensed drivers in the US, female-headed households in the census report not having access to a vehicle 42% more often than male-headed households. We also see a gender gap in the adoption of electric vehicles. According to 2022 registration data, women account for just 28% of new EV registrations, compared to 41% of new registrations of all personal vehicles.

In Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez outlines how cars are designed for the “average male” using crash test dummies that are significantly taller and heavier than an average woman. As a result, when in a car crash, a woman is 47% more likely to be seriously injured than a man, and 17% more likely to die, given similar crash conditions. It’s gut wrenching to think about my loved ones who shoulder this extra risk every day.

Transportation is inextricable in our lives, and so these transportation inequities compound others. Petroleum refineries that produce gasoline pose serious environmental justice issues, and come with air and water quality hazards that disproportionately harm women’s health. Lack of reliable transportation can impose extra barriers for people who need to travel out of state to seek an abortion and other medical care. Heavy-handed zoning for single-family homes encourages car dependence, but also isolates women from others outside their family and adds barriers to sharing care work, which women already disproportionately take on, with a wider community.

Amidst all of this, it’s important to note the diversity of experiences among women. For example, most transportation research groups people into a binary, “male” or “female”, which often neglects the diversity of ways gender shows up in transportation. Non-binary women have different experiences than those who identify as female. Further, the intersection of gender and other characteristics such as race leads to distinct travel patterns. For example, women with lower incomes, particularly women of color, travel further than other workers. However, averaged over the whole population, men travel more miles than women. With these added dimensions, there is a glaring data gap in accounting for these diverse experiences.

After all, when we’re talking about women, we’re talking about all women: women of color, working-class women, women with disabilities, LGTBQ+ women, elderly women, as well as white economically privileged heterosexual women.

Lack of women in the profession leads to a system designed for men

While all transportation professionals have a responsibility to design an inclusive system, participation of women is a key factor in ensuring important perspectives are captured. For example, research in 2000 on risk perception by UCS Vice President of Science & Innovation Melissa Finucane has shown that white men in the US see threats from climate change to automobile accidents to air pollution as less risky than white women and women of color do. Diverse perspectives are needed to balance risk perceptions on transportation and climate decisions.

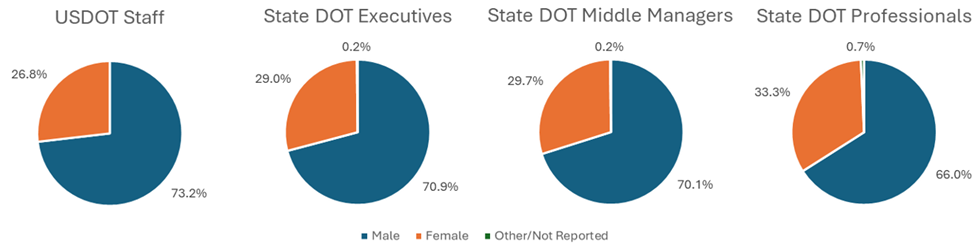

Recently released HR data from the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials shows that the highest-ranking executives at the decisionmaking helm of state departments of transportation are only 29.0% female. It doesn’t get much better as you go down the organizational ladder – mid-level managers were only 29.7% female, and all other professionals were around 33.3% female. This matches the federal level too – as of February 2024 only 26.8% of US Department of Transportation staff were female, and that number hasn’t changed much since 2000.

Among transportation researchers, while women have increased their representation among doctoral degrees in recent years, they still are highly underrepresented in among engineering PhD’s (24.1%). UCS regularly attends one of the biggest transportation conferences in the world, the Transportation Research Board’s (TRB) Annual Meeting, in which only 27.5% of attendees identify as female.

The underrepresentation is compounded by the gender pay gap, where on average women earn 78% of what men earn, according to Census data. This largely matches data for the transportation industry specifically.

The women fighting for more inclusive movement

Despite these barriers, for decades, women across the country have been leading the way. I’ll end with a non-exhaustive list adding to the one above of some of these people and organizations to support and keep an eye out for:

- TRB’s Women and Gender in Transport Committee and upcoming 7th International Conference on Women and Gender in Transportation (WGiT)

- WTS International (professional association for women in transportation)

- Eno Transportation Weekly’s Women Take Over (Week of March 25, 2024)

- Women Mobilize Women

- COMTO’s Women Who Move the Nation

- American Planning Association’s Women & Planning Division

- Subtext, a zine by members of TransitCenter’s Women Changing Transportation Program

- The Gender and Equity Collaborative

- Further research compiled in Transportation, Race and Equity: A Syllabi Resource List for Faculty