Members of the Los Angeles City Council have disgraced themselves over the past year with scandals—including leaked plans to disenfranchise voters of color—forcing out several members. But Angelenos now have an opportunity to improve the design of their government in 2024, at a time when our nation desperately needs solutions for strengthening democracy.

An interim report from the LA Governance Reform Project released earlier this summer provides a crucial starting point for a public conversation to address reforming the Los Angeles City Council in the wake of racism and corruption of the redistricting process that was revealed in an October 2022 report by the Los Angeles Times.

The report makes three important recommendations: ethics reform, the establishment of an independent redistricting commission, and enlarging the size of the council. In the words of the authors, they “hope that this process adds momentum to a longer-term commitment to governance reform in Los Angeles, with due consideration for a host of improvements that might make a difference.”

As an expert in redistricting and electoral system design, I hope to expand the conversation about what effective electoral reform requires. The group’s recommendations on ethics reform and the establishment of an independent redistricting commission are well-reasoned and evidence-based, but I am concerned that the recommendations on increasing the size of the council to 25 members, including four seats elected citywide or “at-large,” errs too far in the direction of what is deemed politically viable, falling short of what is politically necessary to achieve their stated goals of creating “a city structure that is responsive, accountable, representative, and equitable.”

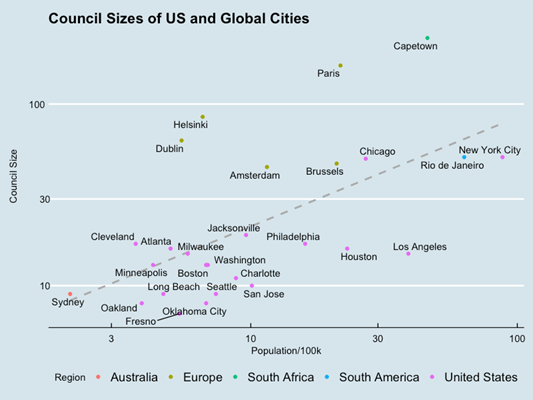

The research team’s recommendation of a 25-seat council is based on looking only at average council sizes in the United States. This makes our largest city councils, New York (51) and Chicago (50), appear to be outliers. The appropriate comparison is with other large, global cities, which shows what comparative urbanists have known for some time, that council sizes in large US cities are unusually small. The current 15-seat council in Los Angeles is ridiculously small for its population by global standards, among the smallest per-capita councils in the world (see Figure 1).

As Figure 1 shows, Chicago and New York are not outliers compared to other global cities. A 45- or 50-seat council for Los Angeles would bring the city closer to several other economic and cultural capitals like Amsterdam, Dublin, and Rio, but still be well below Paris’ 163-seat council, or the enormous 231-seat council in Cape Town, South Africa. At the other end of the scale, many of the world’s global cities including London, Mexico City, and Tokyo, are agglomerations of multiple smaller municipalities. Chicago and New York fit well within the normal range of 45-100 seats typical of large, cosmopolitan cities. A 45-seat LA council would be at the low end of global norms, given the city’s population and global status.

The small councils characteristic of many US cities partially reflect the legacy of institutional racism, specifically early 20th-century Progressive reformers’ efforts to exclude ethnic and racial minorities from political power. Equitable racial representation must be a priority in LA council reform, as racial divisions within the city were at the heart of the redistricting scandal.

US cities have achieved approximate proportional representation for protected racial groups through the design of single-seat, minority-opportunity districts, enforced through the Voting Rights Act. However, this solution only works where groups are geographically concentrated and where there are relatively few communities of interest to represent. Los Angeles today is one of the most diverse cities in the world, where hundreds of racial, ethnic, and language groups make up the city’s population. It is difficult to see how 21 single-seat districts, in which only one coalition achieves representation in a district, will adequately address the competition over racial representation that Los Angeles faces.

The city of New York increased its council size from 35 to 51 in 1991, facing some of the same problems, and in the hopes of advancing similar democratic goals. The General Counsel to the New York City Districting Commission, an attorney from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, focused specifically on problems of interracial conflict and the inevitable trade-offs required when only one racial group can be represented within a multiracial district. These trade-offs, and the carving up of populations along racial lines to determine who gets represented, were the topic of discussion in the now infamous LA city council phone call.

That NAACP attorney, Judith Reed, recommended that New York adopt multi-seat, proportional districts, which would allow multiple representatives to serve a single constituency, incentivizing multiracial coalitions to work together. Instead, the Commission adopted a single-seat districting strategy, forcing them to address questions like, “Is a geographically dispersed minority ‘better off’ with white voters, who may or may not have any sympathy for Latino interests, or with other minority groups, with whom there is the presumption of destructive competition?” Today, New York, like many large US cities, continues to struggle with interracial conflict, low turnout, and largely uncompetitive single-seat districts. They are trying other reforms to induce competition and improve representation, like ranked choice voting schemes in primaries, but the fundamental problems with single-seat representation remain.

Los Angeles has an opportunity to break out of these constraints. Research in the US and abroad has shown that multi-seat districts are less prone to gerrymandering and other forms of manipulation, which is the motivation for reform in LA. Most large, global cities rely on multi-seat, proportional districting and achieve robust representation across racial, gender, language, and other boundaries. Coalitions and parties across the ideological spectrum run, and seat, more candidates of color, and more women, than we often find in US municipal elections. For example, in Amsterdam, five major political parties, including the Greens and Socialists on the left and Christian Unity on the right, in addition to the smaller, ethnic rights DENK party, run and seat candidates of color on the city council. Los Angeles, by contrast, is effectively a one-party regime.

Consider the opportunities that a 45-seat council, built out of eight five-seat districts drawn by an independent commission, would offer residents. Each multiracial district would reflect geographic interests beyond race, while ensuring representation for any coalition, racial or multiracial, successfully organizing just 20 percent of voters, because that is all it would take to win one of five seats.

In line with the LA Governance Reform Projects recommendations, an additional five seats could be elected citywide to incentivize broader coalition building. But instead of using the worst electoral system devised for minority representation—at-large plurality voting—these seats could be elected using the same method as the district elections, commonly known as an open list system.

A common method of election in large cities around the world, the list system was first proposed in the US in 1844 by Thomas Gilpin for Philadelphia elections. From a voter’s perspective, little changes, as you simply vote for a single candidate from a slate of candidates. The vote counts toward the candidate AND the candidate’s slate (the other candidates they are running with), which determines how many seats the slate wins in each district. Competing candidates of color then do not risk “splitting” minority voters. Broader, multiracial coalitions that transcend district boundaries are also rewarded with more seats.

Even a modest proposal of eight three-seat districts and one five-seat citywide district, for a total council size of 29, would likely be more equitable for racial representation than the proposal from the Governance Reform Project. Every voter would have a variety of candidates competing for their support, and every district could represent up to three competing electoral coalitions, better reflecting the true diversity of Los Angeles.

Public opposition to enlarging the council and demands on the capacity of the mayor’s office are cited as major impediments to more effective electoral reform. But a larger city council does not require an expanded role for the mayor or mayor’s staff, as many of the global cities already mentioned rely effectively on a council-manager form of government, with relatively decentralized administrative agencies. As for public opposition to a larger council, that is a question of political will. If the advantages of improved descriptive representation and government accountability are adequately communicated by the reform coalition, I am confident that an initiative on the 2024 ballot would have a fighting chance.

Residents of one of the most diverse cities on the planet could vanquish part of the legacy of institutional racism that continues to plague the politics of our nation. Whether or not a reform coalition is able to mobilize support to adopt meaningful reform depends on the level of community engagement that we will see over the next year. At this stage, Angelenos deserve to at least be informed about how the rest of the world addresses the challenges of equitable racial representation and municipal governance.