Extreme winter weather has revealed the flaws of energy strategies that overly rely on gas. A year ago, I wrote about how Mid-Atlantic fossil fuel power plant owners’ bad practices cost consumers money by reducing power plant capabilities that should be available in cold weather. Soon after I posted that blog, the February Winter Storm Uri wreaked havoc on energy supplies, leading to more than 250 deaths in Texas and Mexico.

The gas industry’s widespread inattention to winter reliability must be addressed, and one way to fix it is for gas-burning power plants to take a closer look at their performance in colder weather.

Last winter, I described how cooler air allows gas-fired power plants to generate more electricity than the plant can generate in hot weather, because cooler air is heavier and able to absorb more heat. Despite this capability, nearly all new gas-fired power plants in the Mid-Atlantic during the past 20 years sought and received limits from grid operator PJM on their ability to use this physical capability through PJM’s process. Failing to implement this cooler-weather capability costs consumers money and makes it more likely there will be another power system failure this winter.

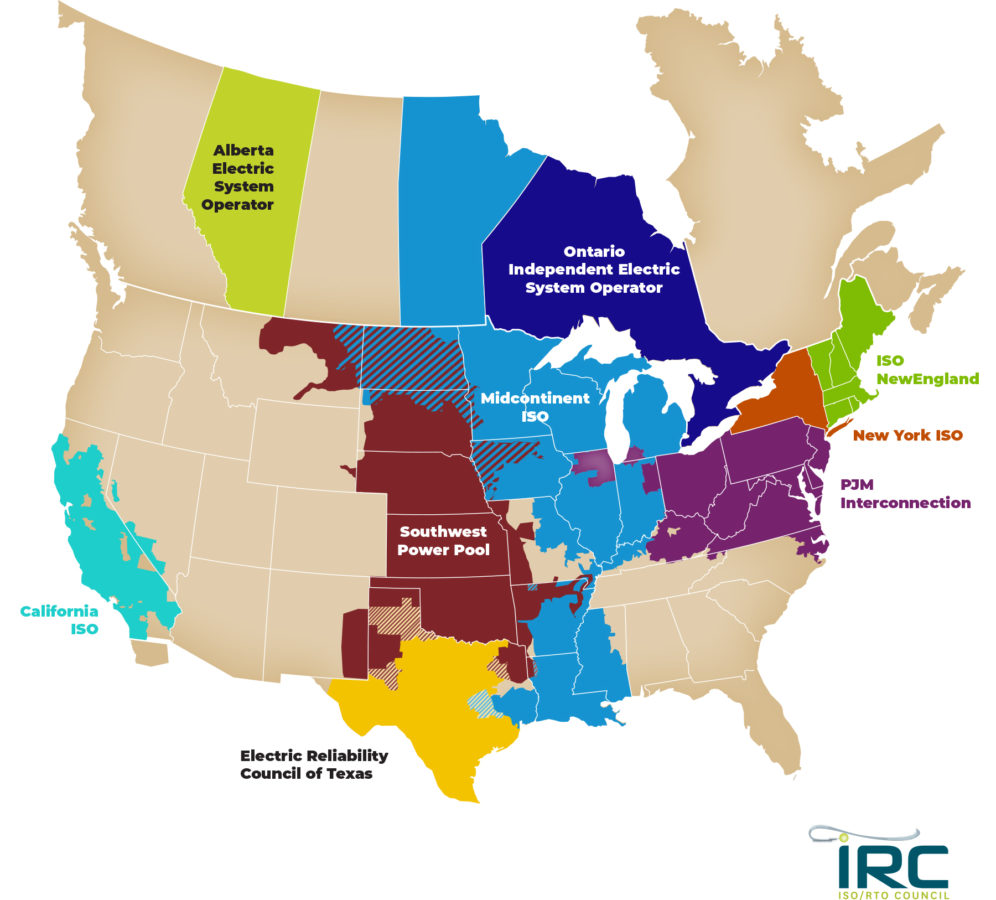

An analysis I conducted after the last February’s energy crisis in Texas found gas-fired plants suppressing their own capabilities in cooler weather in at least 27 states. Plant owners’ decision to report to grid operators no added capability or flexibility from their generators ignores good utility practice. When power plant owners request permission from their grid operator to connect a new power plant to the grid, they are expected to provide both winter (50 degrees F) and summer (90 degrees F) power plant output in the process. This is a standard process for adding large power plants to the grid, with detailed rules and standard forms. In some regions, the power plants provide the added winter capability and flexibility that lowers consumer costs and increases reliability. In some regions, they don’t.

Grid operators in New York and New England are getting this colder-weather contribution from 90 percent of the newer gas-burning power plants, what wonks would call natural gas combined-cycle units. These gas power plants have requested and received permission to operate at higher winter ratings than summer ratings.

In the three other regions of the eastern United States, most of the newer gas power plants have told grid operators that they will not produce more power in any weather than what they can produce at 90 degrees F. The connection requests and resulting plans for the operating gas power plants in the Southwest Power Pool show 33 percent in that 14-state region are providing higher output in cooler weather. In the 24 states in the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) and PJM power pools, only 10 to 15 percent do so. One piece of good news for Texas: The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) reports for the past year approximately 80 percent make the cooler capability available. (There are states that are in more than one power pool.)

The problem of cold weather reliability is caused by power plant owners cutting corners to save money. This is related to, but not the same reason for the energy problems in Texas last February triggered by Storm Uri. There, the biggest problem was gas suppliers—and to a lesser extent power plant owners—that were unprepared to keep their equipment from freezing.

A more widespread problem is due to plant owners showing no interest in how cooler temperatures will affect their plants. Instead of problems cropping up only when temperatures are at record-setting lows, which happened last February, their neglect undermines the grid in the spring, through the fall and winter, and during most of the summer, too. Because the power plants we are calling out choose to keep the hot weather de-rating that applies when the outdoor temperature is at 90 degrees F or above, economic and flexible capability is not available to the grid. That also increases costs for consumers.

The power system’s ability to integrate solar energy is also undercut by these gas plant owners’ wrongheaded decisions. The capability that should be available in cooler weather would provide flexibility for handling the Duck Curve caused by solar energy’s daily pattern. This is most pronounced in cooler weather in the spring, when solar panels are most productive because they work better in cooler ambient air. Using fewer, but more flexible, gas power plants is part of the path to decarbonize the electric supply, but only if they are used correctly.

UCS has been warning about risks of over-relying on gas for years, from reports in 2013 and 2015 to our current call to “red light” US approvals for new fossil fuel development on public land. The practice of ignoring colder weather has serious, near-term risks. If the industry isn’t interested in correcting this problem, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has plenty of authority and opportunity to use incentives, penalties or reliability rules to get gas-burning plant owners’ attention.