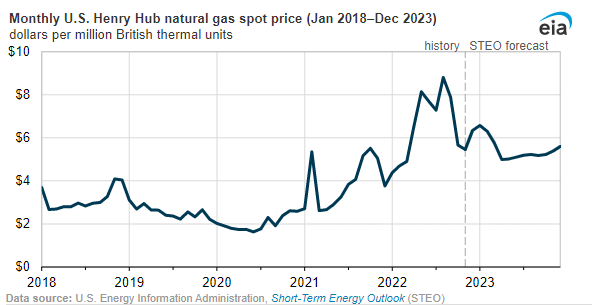

US ratepayers very likely will pay even more for electricity and heating this winter compared to the already-expensive winter of 2021-2022. These higher costs are being driven by a major overreliance on natural gas, which has sharply spiked in price and is currently the dominant fuel source in the US for both home heating and electricity generation.

The US Energy Information Administration is forecasting the wholesale price of gas to reach its highest level since the winter of 2009-2010 in inflation-adjusted terms. Power companies will therefore have to pay more for the fuel, but utilities are generally allowed by state regulators to pass those cost increases onto their customers in the form of higher electricity rates.

Because so many Americans will be paying higher energy bills this winter, it’s worth exploring how we got into this predicament to demystify what some analysts may claim is just free-market fundamentals at work, operating completely out of our control.

On the contrary, the country’s unsustainable dependence on gas is a result of specific policy and regulatory choices, along with investments in energy infrastructure that were driven by those policies. This means that policymakers can make better, science-based choices going forward to reduce US reliance on gas and move toward a cleaner, more affordable energy future.

Debt-fueled boom and gas-friendly policies

To dig into how the country got here, it’s helpful to split up the contributing factors into the three main “gas value chain” categories: the production of gas via drilling (“upstream”), the transportation of gas via pipelines (“midstream”), and the facilities that receive the gas, such as gas-fired power plants (“downstream”).

During the 2010s, there was an explosion of oil and gas production in the United States, a period many now call the “shale boom” or “fracking boom.” Shale is the type of underground geologic formation found in various parts of the country, including the Marcellus shale in the Appalachian region and the Haynesville shale in Texas. Fracking is a shortened version of “hydraulic fracturing,” an oil and gas drilling method that has been around for decades but improved only relatively recently with such methods as horizontal drilling.

However, make no mistake: Technological advancement did not create the production boom by itself. It was facilitated by large financial institutions continuously giving low-interest loans to fracking companies despite the fact that many of those companies could not turn a profit. In fact, the top 28 publicly traded US oil and gas producers lost an estimated $115 billion in the decade leading up to the coronavirus pandemic.

Investors finally started getting tougher on these debt-saddled drilling companies during the pandemic as demand for both oil and gas plunged, pushing a slew of drillers over the edge into bankruptcy. The bankruptcies were set in motion even before 2020. Between 2015 and 2021, 274 North American oil and gas producers filed for bankruptcy with a debt load of $177 billion.

In any case, it turned out that all of this fracked gas didn’t need to be profitable on the so-called “upstream” side to reach its dominant position today. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which has authority over the siting of interstate gas pipelines (the “midstream” infrastructure that transports the gas), is operating under an antiquated policy regime from 1999 that has resulted in the agency approving hundreds of gas pipeline projects (and rejecting only two between 1999 and 2016) without adequate scrutiny of project costs and benefits. FERC tried to update its approach earlier this year, but put that move on pause in March after pushback by the gas industry.

Further “downstream,” gas generally moves from large interstate pipelines to smaller distribution pipeline systems, where it is sent to facilities like power plants to be burned. Much has been written by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and others about how current policy and regulatory conditions favor gas-fired power plants over cleaner resources that don’t even need fuel, such as wind and solar. Included in those conditions is the fact that the utility companies who own—or buy power from—those plants don’t really bear any of the risk of gas price spikes. All that leads us to where we are today.

Ratepayers shoulder the risk

Gas production data suggest that the explosive growth during the fracking boom is over. Gas supply has been struggling to keep up with demand since coronavirus vaccines made available in 2021, which enabled the economy to get back on track more quickly than expected. Recent cold winters, hot summers, and rising exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also are contributing to high US demand. (See my colleague Mike Jacobs’ recent blog for more on LNG exports.)

The price spike due to short supplies has forced US ratepayers to foot the bill for unwise, risky investments made by utility companies and other gas industry players. These companies have spent the last decade locking gas in as the go-to resource for power generation while keeping it around as the go-to resource for heating, thus driving up demand and the price of gas. Consequently, residential gas prices are expected to be 22 percent higher this winter compared to last year’s, and residential electricity prices are expected to be 6 percent higher on average.

While a 6-percent electricity price increase may not sound too large, keep in mind that this jump will be on top of heating bills, which will be particularly high for the nearly half of Americans who mainly heat their homes with gas. (A smaller percentage of homes are heated by other sources, such as electricity or propane.) In addition, the estimate of a 6-percent increase is only an average, meaning that some areas will see much higher rate hikes, depending on how large of an increase that area’s local utility is requesting, and how much of that request is approved by the state’s utility regulatory agency (typically called a “public utilities commission” or “public service commission”).

There are examples from across the country. Appalachian Power is currently seeking approval from Virginia regulators to increase residential electric rates by nearly 16 percent due to higher fuel costs. Duke Energy plans to hike electric bills by 13 percent in South Carolina and Florida starting in January, also due to higher fuel costs. And Eversource Energy’s New Hampshire utility won approval from the state Public Utilities Commission over the summer to increase electric rates by a whopping 53 percent through the end of January 2023 to account for high gas prices in New England.

The companies cited above are investor-owned utilities, which supplied electricity to about 220 million Americans in 2021, or roughly 66 percent of the US population. Shareholders who own these utility companies won’t feel the impact of these fuel-cost increases, because state public utilities commissions generally allow the companies to pass those costs onto their customers in the form of higher rates.

High gas costs won’t be evenly distributed

Cost increases arising from US dependence on gas will disproportionately impact low-income households and communities of color, which tend to have higher energy burdens (i.e., a higher percentage of income spent on energy bills). High energy burdens can result from a variety of factors, including earning lower average salaries, residing in older, less-efficient buildings, and having insufficient access to energy efficiency programs.

A 2020 study found that Native American households’ median energy burden was 45 percent higher than non-Hispanic White households, while Black households’ median energy burden was 43 percent higher and Hispanic households’ burden was 20 percent higher. According to a more recent study, about 16 percent of US households across the board experience energy poverty, defined as having an energy burden of more than 6 percent.

In addition to a host of macro-level environmental and health costs associated with burning more gas, there are other significant non-monetary costs that arise at the household level when families are no longer able to pay their energy bills, which leads to service disconnections. According to a May 2022 report, utility companies cut power to US households more than 3.6 million times since the beginning of the pandemic, forcing those families to decide between paying their energy bills or buying groceries. Even if they decide the latter, they can’t refrigerate or heat any food if their utility services are cut off.

My colleague Alicia Race wrote recently about her own personal experience with utility disconnections when she was growing up. As she stresses, energy access is not a luxury. It provides essential services that can be a matter of life or death for millions of people. Our national overreliance on gas is evidently undermining energy access, not strengthening it, as some fossil fuel industry players would want you to believe.

Don’t believe the industry spin

The oil and gas industry is benefiting greatly from high prices and has showered its shareholders with billions of dollars in stock buybacks as its profits soar to record levels.

In the short term, low supply and high demand for gas has enabled oil and gas companies to make up for a bad financial decade, with 2020 being the worst year for them. But in the long term, they see increasingly strong government climate policies continuing to pop up and understand that if they are going to achieve their goal of keeping the country dependent on their product, they need to keep prices at a socially acceptable level so that people don’t switch to other technologies that are cheaper—and cleaner.

That’s why, since the price spike, the industry has doubled down on lobbying for weaker environmental protections to clear the way for more oil and gas production and the further lock-in of gas pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure.

Industry’s first main tactic for surviving in an increasingly expensive and climate-conscious world is to convince the public that gas is the best way to keep energy affordable. It says that the country is demanding gas—and is going to continue demanding it—so allow us to increase supply so that prices come down.

This argument is opportunistic and completely out of line with the realities of energy market risk.

It is painfully obvious what happens when the US energy sector relies too heavily on gas: prices become unaffordable and too many families on the brink are forced to make heartbreaking economic choices. Even if supply increases and prices drop in the short- to medium-term, that by no means would prevent another price spike from happening again, particularly now that US LNG exports have tied US supplies to a global commodity market after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, making fuel prices vulnerable to the volatility of geopolitical turmoil.

Industry’s second main tactic is to convince lawmakers and the general public that gas is a clean fuel, and therefore the country should increase its reliance on it to speed up the transition from coal. Oil and gas major ConocoPhillips’ website says gas is “one of the safest and cleanest fuels available” and that when it is burned, it “produces mostly carbon dioxide and water vapor—the same substances emitted when humans exhale.” Likewise, pipeline giant Williams Companies now refers to its gas projects as “clean energy” projects.

These claims just add to the deluge of greenwashing and disinformation from the fossil fuel industry.

Here’s why the claims are wrong:

UCS has pointed out that while gas burns cleaner than coal at a power plant, it is far from a “clean” fuel because it still results in significant toxic air pollution. Further, while gas emits less carbon dioxide than coal when burned, its main component is methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas when it leaks into the atmosphere further upstream—a fact that ConocoPhillips conveniently left out on its website. Methane is more than 80 times as powerful at warming the planet over a 20-year time frame than carbon dioxide.

Methane is also a fast-acting greenhouse gas in terms of its impact on the climate. That means that it is critical to cut those emissions today to stave off some of the worst potential consequences of climate change.

There’s a better way forward

There are many promising signs that the country is making progress on a path that is aligned with climate science and energy market risk management. From 2019 through 2021, additions of large-scale generating capacity have been led by wind—not gas—and the US Energy Information Administration says solar power is on track to lead this year. Solar was actually the leading capacity addition from 2019 through 2021 if you include smaller-scale systems such as rooftop solar. All of this new capacity will lower US emissions and reduce exposure to gas price spikes such as the one we are experiencing today, since the “fuel” from these sources—mainly wind and sun—is completely free, and these sources can displace more expensive, fuel-dependent ones.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law in August, will also turbocharge new clean energy, clean vehicle, and clean building infrastructure. Overall, the law is a $369-billion investment in climate and energy solutions, and is expected to reduce economy-wide emissions by 40 percent below 2005 levels.

Federal agencies are currently in the process of implementing the various IRA provisions. UCS and its allies are actively engaging with these agencies to ensure that this implementation results in just and equitable outcomes, and that legacy fossil fuel industry players are not able to game the system in their favor or exploit any loopholes.

Regardless, energy bills will spike for many families this winter. It didn’t have to be this way and it can be prevented from happening over and over again in the coming years by reducing US dependence on gas and ramping up the adoption of renewable energy.

This blog has been updated to fix characterization of methane emissions.