It’s that time of the year again, when many of us are relieved that the bitter cold weather is finally behind us, yet apprehensive about the dangerously extreme weather events that are likely to come. May is not only the first month of Danger Season, it is also wildfire awareness month, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

With high-fire-risk months still ahead of us, 2024 has seen significant wildfire damage already. The largest fire so far this year has been the Smokehouse Creek Fire in Texas, which tends to experience the most wildfires in winter, unlike western states. The fire was the largest in the state’s history, burning more than a million acres, killing two people, and passing within a few miles of a nuclear weapons facility in the area.

The Smokehouse Creek fire, along with smaller fires that burned in the region simultaneously, also knocked out power for thousands of people, due to both preemptive shutoffs of power lines, as well as direct grid damage.

In this case, grid damage appears to have sparked the Smokehouse Creek Fire as well. Xcel Energy acknowledged its equipment’s apparent role in igniting it, and about a month later, the same utility company preemptively shut off power to 55,000 of its Colorado customers to prevent another fire from being sparked in that state.

Grid failures can cause wildfires. Wildfires and fire risk can cause more grid failures. In this blog post I’ll walk through how wildfires and grid failures have exacerbated each other in recent years and continue to do so, sometimes in deadly ways.

But first, it’s critical to understand this phenomenon’s connection to climate change. Both fossil fuel and utility companies bear some responsibility for wildfires’ damage, and must be held accountable to ensure disadvantaged and low-income communities aren’t left to shoulder the costs and impacts of these disasters. With that, let’s get into the details.

Emissions fuel more wildfires

Since 1960, the five years with the most area burned by US wildfires have all been within the last 20 years. While 2023 was a low year in terms of total acreage burned in the United States, some 2.6 million acres were still consumed by wildfires, including in Maui where one of the deadliest fires in US history killed more than 100 people. In addition, Canada experienced its worst wildfire season on record last year, which drove significant reductions in air quality in certain parts of the country as well as the United States.

Forests in western North America are particularly susceptible to wildfires due to development, land management, and climate change. The rising amount of area burned is attributable in part to an increase in “vapor pressure deficit”, which is essentially a measure of the air’s ability to dry out plants and soil.

Last year, my UCS colleagues working on climate science and corporate accountability found, in a peer-reviewed study, that 37% of the area burned in western North America since 1986 is attributable to the carbon emissions of just 88 fossil fuel companies and cement manufacturers. That 37% equates to 19.8 million acres scorched in the western United States and southwestern Canada.

While climate change has not been specifically linked to the Maui and Texas wildfires, broken power lines are being investigated as a cause of both of them. These would not be one-off instances if the power lines are found to have sparked the fires; this is a growing problem that more and more utilities, and the communities they serve, are having to grapple with. So how extensive is this problem and how does it happen?

Grid failures start fires

From 2001 to 2023, roughly 92 million acres in the United States have been burned by lightning-caused fires, and about 68 million acres have been burned by fires caused by human activity, electrical operations being just one example. Fires sparked by failures of power lines and associated grid equipment present an area of increasing concern in the era of climate change, with a geographic scope that appears to be expanding within the United States.

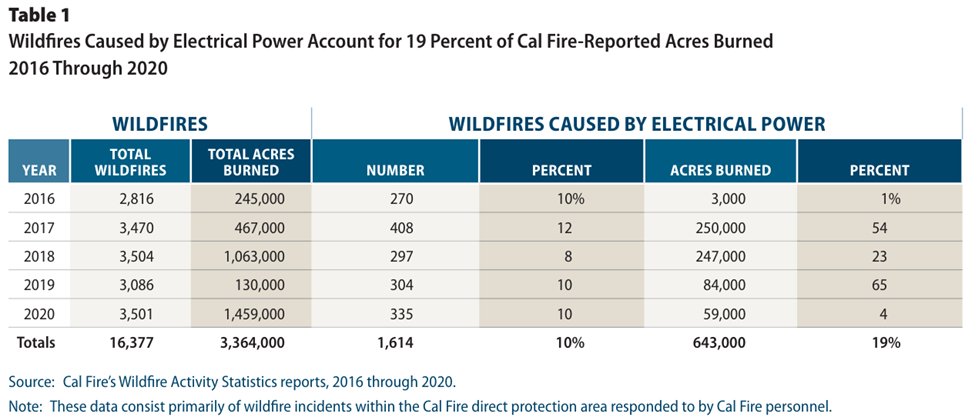

A utility industry group executive recently told the New York Times that utilities’ equipment causes less than 10% of fires nationally. That percentage was actually the same for wildfires between 2016-2020 in California – a high-risk wildfire state.

However, those California fires caused by electrical equipment accounted for 19% of the total acreage burned in the state during the same period, and in some years, they accounted for the majority of the burned acreage. This discrepancy between number of fires and area burned by fires aligns with research finding that human-caused fires spread more rapidly than naturally caused fires, since human-caused fires tend to start in hotter, drier conditions.

There are various mechanisms through which electrical operations can spark wildfires, both on transmission and distribution grids. Downed power lines can remain “energized” as they fall to the grass below. Trees and other vegetation can come into contact with lines and create an improper flow of electricity (called a fault), causing sparks to fly. Parallel lines can even blow in the wind and “slap” together, creating a different type of fault and a fire-ignition risk.

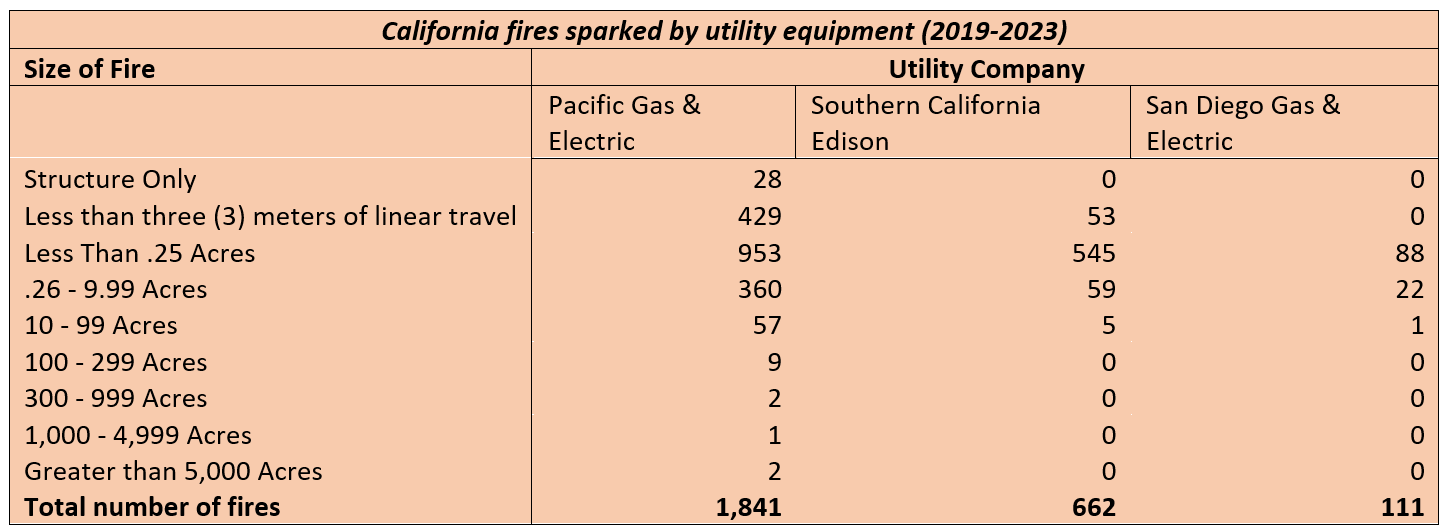

Many fires are put out before they grow to a dangerous size. The grid equipment of California utilities, for example, starts hundreds of fires every year, but most of them are put out rather quickly before spreading.

However, extinguishing fires is challenging in dry, warm, and windy weather conditions, which are only getting worse with climate change and can spread fire at a terrifyingly high rate. In November 2018, the Camp Fire in northern California was sparked by a nearly 100-year old transmission line owned by Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), which negligently failed to properly maintain it. The wildfire spread across more than 150,000 acres, killed 85 people, and destroyed the California towns of Paradise and Concow, with most of the damage taking place in just the first four hours. The resulting liabilities helped push PG&E into one of the most complex bankruptcy cases in US history.

PG&E emerged from bankruptcy back in 2020 and is gradually doing the long-overdue work needed to improve the safety of its infrastructure, but this will be a long process, and the company’s equipment has started multiple other deadly fires since the Camp Fire.

Utilities outside of California are also facing liabilities for their potential roles in starting wildfires, including Xcel Energy in Texas as previously mentioned, and Hawaiian Electric in Maui. Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary PacifiCorp expects it could face $8 billion in liabilities for fires it may have started in both California and Oregon.

As wildfire risk worsens with climate change, more and more utilities are increasingly turning to a risk-management method that was not common at all just a decade ago: purposely shutting off power to customers, as I mentioned above.

Fire risk forces intentional grid shutoffs

On a fateful dry, windy day in early November 2018, PG&E announced that it was no longer planning to shut off power to customers in northern California because weather conditions had improved, making its grid infrastructure safe to operate. Later that day, the Camp Fire was ignited by PG&E equipment, starting the deadliest wildfire in California’s history.

Had PG&E either properly maintained its infrastructure, or decided to shut off the power that day, 85 people likely would not have lost their lives. This tragedy, along with thousands of other utility-caused fires, is why PG&E and other California utilities have since formalized so-called public safety power shutoff programs. The idea is that if utilities “de-energize” their power lines until the unsafely dry and windy weather conditions subside, a wildfire won’t be sparked.

The resulting tradeoffs for utility customers, who are left temporarily without power, range from minor inconveniences to full-blown matters of life and death. When PG&E proceeded with a 2-million-customer public safety power shutoff event in 2019, Robert Mardis Sr.–a man who used an electric oxygen tank to aid his breathing–tragically died just minutes after his power was shut off.

In 2022, my UCS colleague Mark Specht authored a blog post analyzing public safety power shutoff events in California, finding that utilities have reduced the overall scope of these events since PG&E’s large 2019 power shutoff. But the power shutoff events continued to last quite long, averaging one to two days, and this practice persists to this day. Southern California Edison shut off power to more than 5,000 customers as recently as December 2023, with the event lasting roughly two days.

While this method of managing wildfire risk can be annoying, inequitable, and sometimes outright dangerous, utilities outside of California are nevertheless increasingly turning to it due to wildfires’ catastrophic potential. A number of states have either already experienced public safety shutoffs, or are served by utilities that have formed protocols to declare such events. These states include Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Texas, Utah, New Mexico, Idaho, Arizona, and Louisiana.

To sum it up, wildfire risk is making our grid less reliable due to the resulting need for public safety shutoff events. But even with such programs in place, fires of course still break out, and can have an even more direct impact on the power grid.

Wildfires pose direct, physical threats to power grid

Wildfires can impact many key components of the power grid, including transmission lines, distribution lines, and even generation facilities such as power plants.

Transmission lines are typically suspended high above ground by steel or aluminum towers, making them relatively well-positioned to avoid direct destruction by wildfires, although destruction still occurs in extreme cases. But fires can also cause transmission lines to “trip” offline automatically as a protective measure to isolate “faulty”, or unsafe, electric current from the rest of the grid. Wildfires’ intense heat can cause excessive line sagging toward the ground, and the soot and smoke in the air can weaken the lines’ insulation, both of which can make faults more likely.

Distribution lines are buried underground more often than transmission lines, which protects them from wildfire damage. But aboveground distribution lines are still very common and many of them are suspended by wooden poles, making them more vulnerable than transmission lines to being burned down completely. From 2000 to 2016, wildfire damage to California’s transmission and distribution systems amounted to more than $700 million.

Wildfire also poses risks to generation facilities, even though that subject is less discussed than the threat to transmission and distribution. Smoky and sooty air can decrease output from solar facilities, and fires themselves can sometimes directly threaten fossil fuel power plants. In 2019, a fire in Maui came within 150 feet of an oil-fired power plant. In 2021, a fire breached a coal plant in Turkey, prompting evacuations and the removal of explosive substances from the plants.

The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) also published a report earlier this year recommending that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) better account for climate impacts in its risk assessments of nuclear plants, including the risk from wildfires. The report found that roughly 20% of the nation’s nuclear plants are located in areas with high, or very high, wildfire risk.

In addition to increasing the potential for onsite fires at nuclear plants, wildfires can cut off external grid power that the plants need for keeping their reactors cool. Once grid power is cut off, the plants must resort to onsite sources of backup power, such as diesel generators. A complete and prolonged cutoff of external power would lead to a disastrous meltdown similar to that of the Fukushima Daiichi plant in 2011. While US regulators implemented additional safeguards in the wake of that disaster, questions remain about their effectiveness.

Looking ahead – managing wildfire risks

We’ve entered a new era of wildfire damage, and we know that, at least in the western United States, this is due, at least in part, to climate change. While we should continue to mitigate these changes to the global climate by transitioning to a clean energy economy, we are now well into the phase of adapting to this new world and managing the “locked-in” risks that lie ahead.

Policymakers and utilities must act on the wide array of environmental justice and equity considerations while proceeding with this wildfire risk management. Understanding these evolving threats to communities will require good data collection on utility-caused fires, and a commitment to transparency. California currently appears to be an outlier in publishing such data. Other states must do better.

In any case, it’s safe to assume there are going to be many disruptions and costly changes moving forward, and these impacts must be alleviated for already-disadvantaged communities. For example, there are solutions that can mitigate the impacts of public safety power shutoff events, which can be very dangerous for those living with disabilities. Utilities can also be proactive in using the wide array of available wildfire modeling tools, and can make investments to ensure that the same households aren’t getting hit with public safety shutoff events over and over again.

But another area that deserves a whole separate blog is the enormous costs that come with such wildfire adaptation investments. Utilities in California are spending enormous amounts of money on undergrounding power lines, trimming trees, installing fire-detection equipment, and other measures aimed at reducing the risk of sparking another catastrophic blaze.

As the potential grows for similar wildfire investments to spread beyond California, policymakers must use their authority to minimize the resulting economic harm to low-income ratepayers. Those ratepayers are already spending far too much of their incomes on energy bills and, of course, they’re not responsible for the situation we’re in.

Emissions traced to fossil fuel companies, on the other hand, have contributed to 19.8 million acres of wildfires’ destruction in the western half of the continent, as the previously mentioned UCS study found last year.

The UCS study also called for fossil fuel companies to pay their fair share of climate-related damages. Ongoing climate-damage and deception lawsuits brought by more than three dozen US states, cities and counties against a subset of these companies could force them to pay for their share of the damages, and those funds could be used to help us more equitably adapt for the future of wildfires.

We can’t undo the scorching of entire towns and the loss of human lives, but pressing for accountability from both fossil fuel and utility companies for contributing to such devastation can at least start to resemble justice.