In late April, California air regulators are poised to pass one of the most meaningful regulations to reduce pollution from commercial trucks, vans, and buses.

The Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) rule, which I’ve blogged about in detail before, will phase out fossil-fueled trucks over the next several decades. This rule expands the benefits of the landmark Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) rule, which compelled manufacturers to sell an increasing number of zero-emission trucks, by requiring that nearly all new medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs) sold in the state be free of tailpipe emissions by 2036.

Together, these standards will accelerate California’s necessary transition to a cleaner and more efficient freight system, increasing the estimated number of electric trucks on our roads and highways by 70% in 2050. These clean trucks will deliver health-related and economic benefits and provide much-needed relief to communities living close to industrial corridors, ports, and railyards. Although not immune to imperfections and challenges, the rule represents a massive step in the right direction and away from the diesel pollution that fouls our air and chokes communities.

What’s in the proposal?

The current draft of the ACF rule was released in late March and made several changes to the version that the California Air Resources Board (CARB) heard back in October 2022. The four primary parts of the regulation remain: electrification requirements for large commercial and federal truck fleets, flexible electrification requirements for state and municipal truck fleets, 100% zero-emission drayage truck operations by 2035, and a 100% zero-emissions MHDV sales requirement. These parts have three high-level impacts:

- Increasing electric truck purchase requirements for large commercial, federal, state, and municipal fleets, beginning as early as 2024 and ramping up to a 100% zero-emission fleet requirement in 2042, based on vehicle category.

- A full transition to electric drayage truck operations in 2035. These trucks, which move shipping containers and goods from ports and railyards, are among the dirtiest on the road and are a primary source of air pollution in disproportionately impacted communities.

- After 2036, all new MHDVs sold in California will be electric.

There are more than 1.8 million commercial trucks on California roads, and although they make up just 7% of vehicles on the road, these trucks are responsible for more than one-quarter of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, more than 60% of smog-forming nitrogen oxides (NOx) and more than 55% of lung- and heart-harming fine particulate (PM2.5) pollution from vehicles.

The more significant changes: some good, others not so great

One of the most significant changes in the final proposal is the acceleration of the 100% zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) sales requirement from 2040 to 2036. This small change is massively impactful and is estimated to put an additional 130,000 electric trucks on the road by 2050, decreasing fuel and maintenance costs to truck fleets and resulting in an additional $300 million in net savings to fleets in 2050. According to our research, these additional electric trucks would increase the health benefits of the rule by about 10% with significantly fewer illnesses and premature deaths.

Unfortunately, not all the changes were so great—one notable revision would delay the electrification of thousands of natural gas-fueled waste trucks by several years. Although the change is meant to allow flexibility for waste fleets that run on biogas captured from landfills, compost, and wastewater treatment, its broad language would allow waste trucks that run on fossil natural gas to take advantage of the delay by purchasing out-of-state biogas credits for their trucks. This change is unfortunate, given that these trucks are among the most well-primed for near-term electrification. In fact, a recent report estimates that waste trucks will transition to ZEVs faster than most other truck types by the end of the decade due to competitive prices of electric models.

Most changes in this final draft were small tweaks to increase compliance flexibility for fleets through targeted exemptions. These include cases of delayed charging infrastructure construction, canceled or delayed vehicle deliveries, and the like. The hope is that these exemptions won’t need to be tapped regularly as the market for clean trucks expands, production catches up to the demand for electric trucks, and the work to install charging infrastructure accelerates and streamlines. The new language also allows additional flexibility for municipal and state fleets through an alternative “ZEV milestone pathway” in the commercial/federal high-priority fleet portion of the rule. This pathway would set ZEV requirements for the in-use fleet and mandate the retirement of polluting combustion trucks after 18 years or 800,000 miles, rather than only requiring newly added trucks to be zero-emissions. This change gives options to public fleets to meet their individual needs while still ensuring that their trucks transition to ZEVs on a feasible timeline.

A notable missed opportunity

One important change that I, along with other advocates and researchers, pushed strongly for was that the ACF regulate more of the dirtiest trucks on our roads. I’ve previously blogged about the need to focus on electrifying semi-trucks, but the threshold at which fleets would be regulated under ACF is set at 50, regardless of the likely emissions from a fleet. This means a fleet of 10 semi-trucks would not be covered under the rule, but a fleet of 50 delivery vans would, despite the former fleet polluting at significantly higher rates than the latter.

Not focusing on the disproportionately negative impact of big rigs will allow thousands of the most polluting trucks on the road to continue operating. Many smaller fleets of tractor trucks would be electrified under the drayage requirements of the rule, but communities close to inland warehouses and logistics facilities far from marine ports and railyards may see fewer pollution reductions.

This is a missed opportunity for the rule to guarantee emissions reductions from the most polluting trucks, but it does present an opportunity for future rules and programs to focus squarely on small fleets. A more targeted rule could address some of the perceived concerns around regulating small fleets by creating additional implementation flexibilities, incentives, and/or low- or no-interest loans.

ACF delivers meaningful benefits

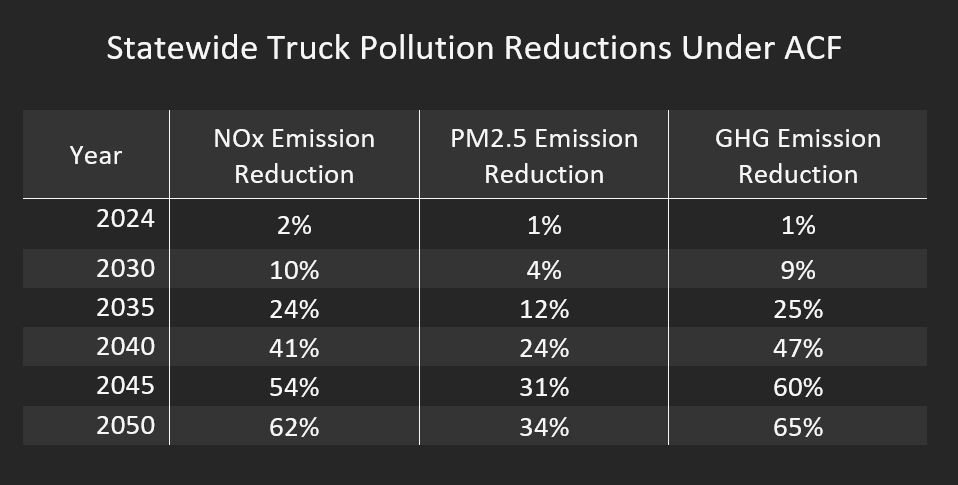

The ACF will deliver significant health and economic benefits to the state. CARB’s most recent Environmental Analysis for the rule estimates that the ACF will reduce MHDV emissions of ozone-forming nitrogen oxides by more than 60% and lung-damaging fine particulates by around 35% in 2050. Similarly, the rule is estimated to reduce climate-warming GHG emissions from trucks by around 65% in 2050.

The benefits delivered by ACF will lead to significant decreases in negative health outcomes due to cleaner air and reduced climate-warming pollution. Statewide, ACF is estimated to result in 2,500 fewer premature cardiopulmonary deaths, nearly 900 avoided hospitalizations for cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, and around 1,200 avoided emergency room visits through 2050. Over half of these health benefit estimates are concentrated in the pollution-plagued South Coast region of California, which is home to some the highest freight traffic in the country.

The rule is also estimated to result in nearly $48 billion in net savings to fleets through 2050. While zero-emissions trucks typically have a higher sticker price than their combustion counterparts today, this price is declining and many fleets will be able to take advantage of purchase incentives in the recently-passed Inflation Reduction Act. The primary factor in the economic benefits to fleets is reduced fuel and maintenance costs, which are estimated to be nearly $59 billion and $25 billion respectively through 2050.

Making electric trucks work for California fleets

Truck fleets have expressed both excitement and concerns about ACF during this time of needed accelerated change. However, the rule as proposed is both reasonable and feasible. Its multiple compliance pathways largely follow declining cost projections for electric trucks, and the rule includes generous exemptions designed to address concerns from fleets and help them comply if obstacles arise.

Flexible compliance pathways

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) has baked in flexibility throughout the ACF by providing multiple compliance pathways for fleets. At the highest level, the rule allows fleets to comply either by requiring only zero-emission truck additions to the fleet after a certain date or allowing fleets to phase in zero-emissions trucks over a longer period of time based on annual fleet milestones.

For example, a fleet comprised mostly of smaller home delivery vehicles may choose to only purchase ZEVs after 2024 to comply with ACF, given these vehicles already have total-cost of ownership upsides. However, a fleet with harder-to-electrify vehicles could choose to turn over their fleet to ZEVs according to the annual milestones over the course of many years. A long-haul trucking fleet, for example, would have until 2030 to prepare their transition and would not have to fully electrify their fleet until 2042, nearly two decades from now.

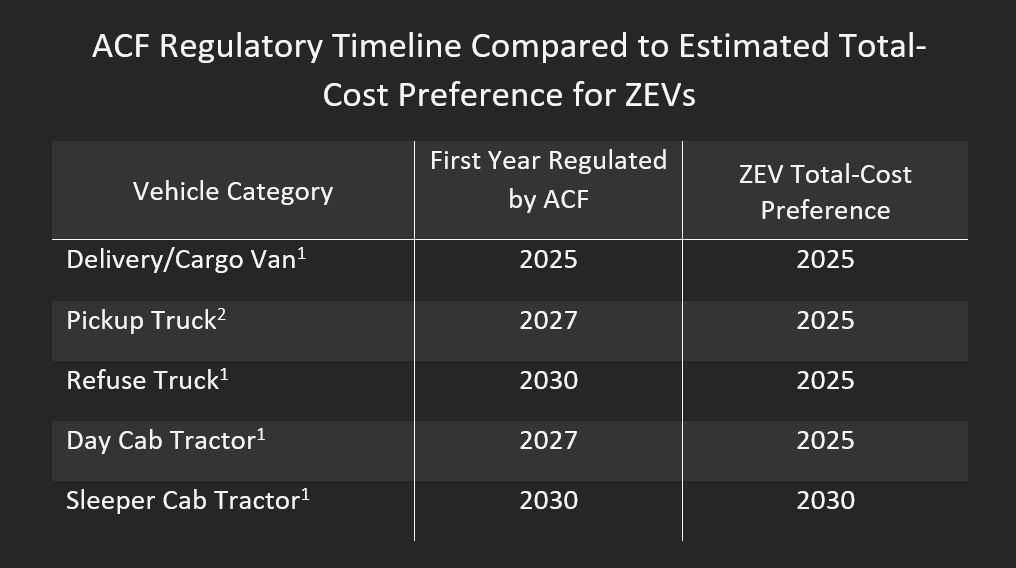

ACF is not like flipping a switch, but rather a gradual sunrise. This regulation ramps up over the course of nearly two decades and begins with requirements for the easiest-to-electrify trucks, like delivery vans, box trucks, yard tractors, and small charter buses. Here in the Bay Area where I live, it’s not rare to see these ZEVs on the road today. Harder-to-electrify vehicles like long-haul tractors and concrete mixers won’t have to comply at all until the beginning of the next decade, though they may begin to transition sooner given the economic upsides of electric vehicles.

Electric trucks deliver savings to fleets

In nearly every case, electric trucks will have a preferred total cost of ownership before they are ever regulated under ACF (see figure below). The numbers, in fact, could convince fleets to transition even faster than what is required under the ACF. Some electric truck types like home delivery trucks, large box vans, and refuse trucks can already have a lower upfront purchase price, given the new commercial EV tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Even in cases where an electric truck’s sticker price is more expensive than a fossil-fueled model, the significant fuel and maintenance costs savings outweigh the additional upfront purchase costs. CARB estimates that fleets will save more than $84 billion in fuel and maintenance costs through 2050 under ACF. Yes, there will be costs for installing charging infrastructure and facility upgrades, but these are far outweighed by the fuel and maintenance savings.

Exemptions for tricky situations

Some fleet owners are keenly aware of the upsides to transitioning to electric vehicles, but have voiced concerns about market uncertainty, delays in installing infrastructure , and, for more rural fleets, whether their electricity grid can handle the additional energy demand. CARB has a fix for that—ACF includes targeted exemptions so fleets can stay in compliance and keep moving people and commodities.

Say you’re a fleet owner and you’ve been planning to transition to ZEVs under the rule. You’ve ordered the trucks you need, planned to install chargers at your facility, and worked with the local utility to ensure adequate electric capacity is available. If any of these processes to transition to zero-emission vehicles are delayed, CARB has included clear exemptions that allow your fleet to still comply with the rule. Although there are more than 160 models of electric MHDVs in nearly every class and configuration today (and more than 200 if you include transit and school buses), if an applicable vehicle isn’t available to meet a fleet’s specific needs, there’s an exemption. Even if you order a vehicle and its delivery is delayed or canceled, there’s an exemption.

In short, fleets that do their due diligence will not be penalized under the rule. I doubt these exemptions will be tapped often, however, given the slow ramp of ACF requirements, the economic benefits of electric trucks, the quickly expanding market for electric trucks, record federal investments, and substantial incentives for infrastructure development, and growing planning efforts among utilities.

An opportunity for California to continue leading

Although the federal government has shown some recent momentum towards truck electrification through its approval of the ACT waiver, the Environmental Protection Agency’s recent proposal on zero-emission trucks misses the moment. Together, the ACF and ACT will supercharge the market and adoption of clean trucks in California, but the current draft of the federal greenhouse gas standards for trucks falls short of zero-emission truck market expectations and electrification targets set by manufacturers themselves.

California is leading the way in cleaning up truck pollution and we know that well-designed policies drive innovation and markets. Thanks to the ACT, manufacturers are already rolling out an increasing number of pollution-free MHDVs. Now, CARB should adopt the ACF to speed the shift to all-electric trucks and put us on the road away from diesel pollution and toward a future of cleaner air and a more stable climate.