At certain times of year (the holidays, back-to-school week, Amazon “Prime Day”), my neighborhood can feel like package central, with trucks from UPS, FedEx, and the post office making multiple trips a day. But there’s no comparison to neighborhoods closer to major nodes in the freight system. Take the intersection of South Ashland Avenue and West 35th Street, in the McKinley Park neighborhood of Chicago, where homes sit across the street from an Amazon warehouse, and where people walking to nearby parks, schools, and churches contend with traffic from several freight facilities. On one day in June 2023, 4,084 trucks and buses rolled through the intersection, according to data collected by the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization and the Center for Neighborhood Technology—with one passing through every 10 seconds during the busiest parts of the day.

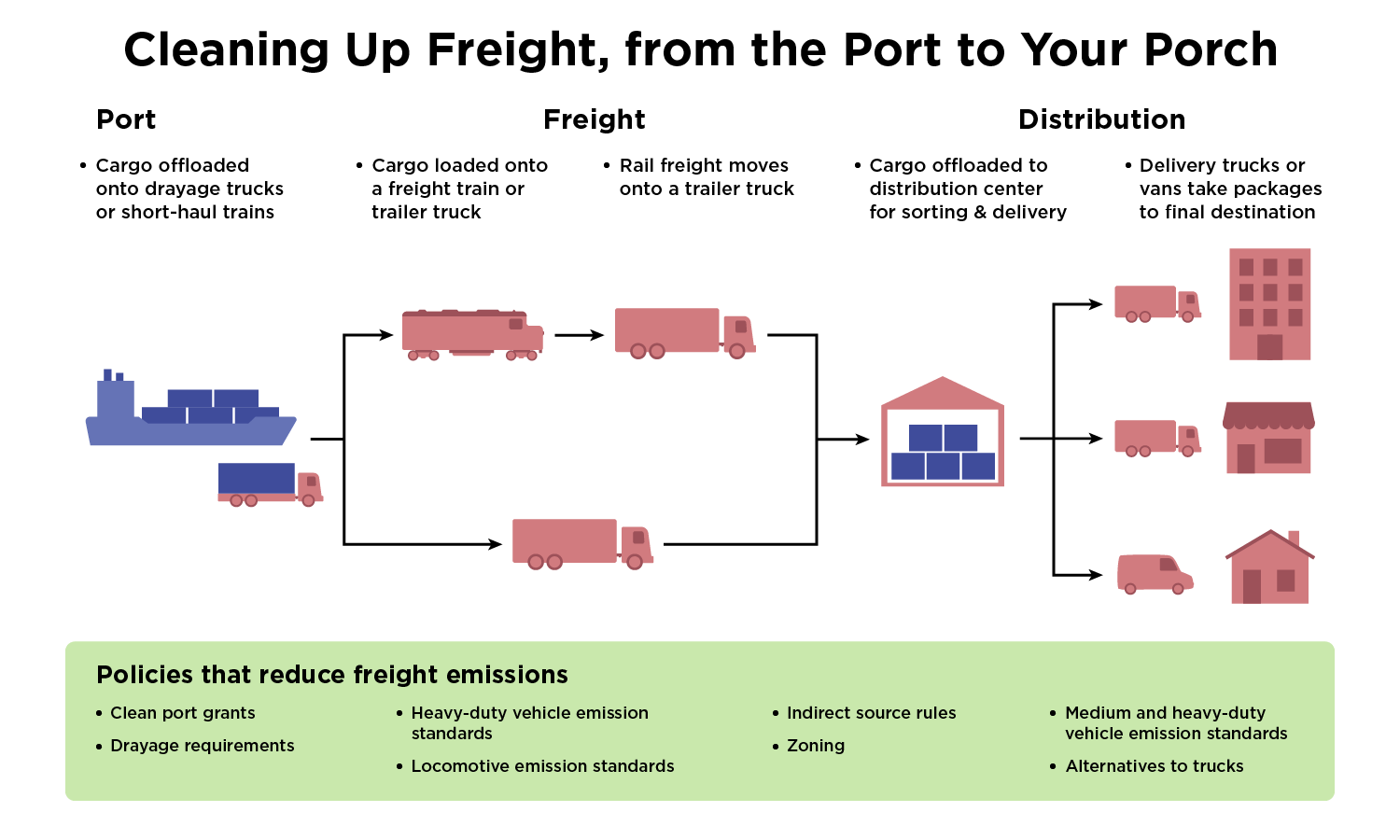

Our freight system is a complex web of logistics. A typical online purchase (like the new bathtub stopper I bought online this month) might follow a journey like this:

- Long before I ordered it, the item traveled on an international container ship which docked at a US seaport.

- Its container was taken off the ship, probably onto a drayage truck (a truck which makes short trips between the port and facilities where cargo is moved onto other vehicles). At some ports, trains fill this role as well.

- From there, the container moved onto a trailer truck or freight train for a trip of a few hundred miles to a local distribution center (if it was on a train, it probably moved to a truck for the last leg of this trip).

- At the distribution center, workers opened the container, sorted its contents, repackaged my bathtub stopper, then put it on a delivery van to be dropped off on my front porch.

This network can feel almost miraculous at times—but it comes with a harmful side. Freight has an outsized impact on human health and the climate. Medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (which include the heaviest pickup trucks and vans as well as commercial trucks and buses) make up just over one of every ten vehicles on the road, but are responsible for over half of smog-forming and fine particulate pollution and nearly one-third of climate warming pollution from on-road vehicles.

The pollution from these vehicles is responsible for over 4,400 premature deaths every year, as well as thousands of emergency room visits and millions of lost school days. It is concentrated in neighborhoods like McKinley Park, which sits near e-commerce warehouses, highways, and railyards.

For decades, community groups—especially those in the environmental justice movement—have fought for a cleaner freight system. Andrea Vidaurre, a co-founder of the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice (in California’s Inland Empire), has put it this way: “What ends up in your stores and online shopping carts has to come through neighborhoods like mine first, and before it comes to my community it passes through many others worldwide completely powered by fossil fuels.”

UCS has also worked for many years to clean up trucking pollution, and our work now encompasses other parts of the freight system. There are tools, technologies, and policies that can reduce impact at almost every step in the process—from the moment a shipment arrives at port to the day a package is ultimately delivered to your porch or package room. Here’s what governments can do.

Cleaning up the ports

Nearly 80% of cargo entering the U.S. does so through seaports, the largest of which are massive operations. In a typical day at the Port of Los Angeles, for example, over 12,000 containers of freight are unloaded from cargo vessels (a similar number are also loaded onto ships for export). These containers are offloaded onto “drayage” trucks which make repeated trips between the port and nearby distribution centers or storage yards, where the cargo is loaded onto trucks or trains to continue its journey.

All of this activity makes ports surrounded by dangerous levels of air pollution. Since at least the early 2000s, community leaders and healthcare professionals have referred to the area around the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach as a “diesel death zone.” The port is a major contributor to poor regional air quality, which the South Coast Air Quality Management District has said leads to over 1,600 premature deaths per year.

Similar issues arise around “inland ports” where rail lines and trucking routes intertwine to form massive interchange areas. Children attending school near the San Bernadino Railyard, a major facility where cargo moves from trains to trucks, were more likely to use inhalers and suffer from chronic cough and impaired lung function, compared to students at a school seven miles west. As one community member told researchers, “When the weather is the hottest, that is when we have the most kids that are sick, with little kids getting sick with a horrendous cough, like a smoker’s cough.”

The concentrated pollution around ports demands concentrated solutions, such as:

Targeted grants: The Inflation Reduction Act, passed by Congress in 2022, included $3 billion for a Clean Ports Program run by the Environmental Protection Agency. Last December, that funding was announced—a surge of support for projects like electric cargo handling equipment and vessel shore power (electrical connections so that docked ships don’t run diesel engines to power their lights, climate control, and other systems).

In the Bay Area, UCS has worked closely with the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project and other partners to identify the need for improved air quality. We were ecstatic to see these efforts pay off in a big way through the Clean Ports Program. Among the grants, the Port of Oakland, WOEIP, and other groups were awarded over $320 million to deploy nearly 500 zero-emission drayage trucks, build out charging infrastructure for trucks and cargo equipment, expand local air quality monitoring, and support enhanced community engagement.

Though the Clean Ports Program awards were a one-time infusion of funds, other federal programs can keep up the momentum. The U.S. Department of Transportation administers a Charging and Fueling Infrastructure program, for example, that has supported zero-emission drayage truck charging in Washington State, California, and Nevada.

Zero-emission drayage: Drayage trucks, which make repeated short trips between the port and nearby cargo facilities, are ripe for electrification. Ports and governments can facilitate the change through incentive programs, charging a per-container fee on polluting drayage trucks, and taking advantage of federal and state grants. The Port of Houston (to name one example) is using Federal Highway Administration funding to purchase clean trucks.

A cleaner regional and long-haul trip

The next step in the cargo journey generally involves being hauled close to its final destination. Whether this is a regional journey (most cargo travels less than 250 miles) or a cross-country long haul, it is most likely to be in a truck.

This makes battery-electric trucks one of the most important technologies we have to clean up the freight system. As my colleague Dave Cooke explained last month, battery-electric trucks beat out the alternatives when it comes to climate emissions. In nearly every state, replacing diesel trucks with battery-electric would sharply reduce health-harming pollution—with the benefits improving as electric power moves to cleaner sources.

Companies are increasingly putting battery-electric tractor trucks to work. Pepsi, for example, deploys dozens of electric tractor-trailers in Northern California, some of which take beverages up to 450 miles from a facility in Sacramento.

Pollutant and zero-emission truck rules: Two sets of rules require truck engine manufacturers to sell an increasing number of cleaner vehicles. The EPA requires new trucks to emit fewer greenhouse gases and health-harming pollutants than existing models. California has passed rules that target the same pollutants, but go beyond federal requirements.

Regional and national truck charging networks: For long-haul truck electrification to take off, the U.S. needs a robust network of charging sites where truckers could refuel their vehicles (probably at the same time that they take legally required rest breaks,).

Most of these sites are likely to be privately funded, but governments can do a lot to speed up the creation of this network. Federal scientists have driven progress toward high-speed-charging technologies that can refuel large battery-electric trucks in 30 minutes. Where the need for heavy-duty vehicle chargers can be reasonably foreseen, utilities can proactively build out their grids. The federal government has proposed a national “freight corridor strategy” outlining where it believes zero-emission truck infrastructure is needed first. Federal grants have also served as a down payment toward this system, funding (for example) battery-electric truck charging hubs in Illinois and along the I-95 corridor in Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland.

Cleaner locomotives: Nearly seven percent of cargo moves via freight rail, and while rail is generally more climate-friendly than trucking, it contributes significantly to public health problems in communities near railyards.

The freight rail industry has stymied attempts to clean up locomotives, abusing loopholes in federal regulations. New locomotives must be built to “Tier 4” standards which make them less polluting than older trains, but rail companies have systematically evaded the rule by “remanufacturing” old, high-polluting locomotives instead of buying newer, cleaner models. The majority of trains in service use technology—and adhere to pollution standards—that are decades behind the times.

Environmental justice leaders (under the banner of the Moving Forward Network) had called on the Biden administration to not just close the loophole but to go beyond, given that even the Tier 4 standard is over a decade old and technology has continued to advance. California had also sought to go beyond weak federal regulations, passing an “in-use locomotive” rule that would require trains to operate in zero-emissions configurations within the state. The EPA did not take action on either request, not granting the waiver needed for California to enforce its rule and not issuing new locomotive standards (the chances of either happening under a Trump administration are slim), but the needs remain.

With enforcement of California’s locomotive rule uncertain for now, Congress can still take action. Last month, UCS stood with Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts to support the “All Aboard Act,” which would improve both passenger and freight rail in the country, including funding to electrify freight railyards.

Cutting pollution from warehouses and delivery routes

The second-to-last stop in a package’s journey is often the distribution center, where goods are sorted and packed for delivery. These warehouses have grown significantly with the rise of e-commerce, becoming major concentrations of pollution. Warehouse construction has accelerated since 2010, and new ones tend to be larger “mega-warehouses” with more loading docks and parking spaces. They also are more likely to be clustered together, with some neighborhoods impacted by multiple new warehouses.

“All that carbon, diesel, black smoke, it’s everywhere in our community and we can’t escape it … We want to make sure every resident and ward in the city of Newark has a right to breathe clean air.” Kim Gaddy, the director of the South Ward Environmental Alliance in Newark, New Jersey, told a reporter in 2022. A quarter of children in Newark have asthma, and this asthma is a leading cause of absenteeism in schools, according to a report from Advocates for Children in New Jersey.

A NASA-supported study helps show the national impact. Using data from satellites, a team of scientists found that levels of nitrogen dioxide (which causes respiratory illness) were, on average, 20% higher near warehouses—and that warehouses are located in neighborhoods which tend to have more residents who are Black, Latine, Asian, or who identify with at least two races.

Potential solutions include:

“Indirect source” rules that require warehouse owners to reduce the impact of their facilities: One of the most promising ways to address the issue is by requiring warehouse owners to take responsibility for their impact.

In Southern California, large warehouse operators are now required to adopt plans to cut or mitigate pollution from their facilities—through measures like acquiring zero-emission trucks, installing on-site electric-truck charging infrastructure, and installing air filters at nearby schools, daycares, and hospitals. UCS and local advocates are looking to win a similar rule in New York, the Clean Deliveries Act.

(These rules are sometimes called “indirect source rules,” and are legally defined as such in the federal Clean Air Act. This is because trucks are the direct source of most pollution near warehouses, but the warehouse is the reason so many trucks are concentrated in one area—and thus, the warehouse is the “indirect source” of pollution.)

Clean delivery vehicles: The federal and state vehicle regulations I mentioned earlier all apply to delivery trucks and vans as well. UCS analysis of these rules suggests that, together, they could result in as many as 250,000 zero-emission “light heavy duty” vehicles like delivery vans on the road. Delivery vehicles are currently leading the way on electrification, in part because their business case is so clear. Daily routes are typically under 100 miles (well within the range of current vehicles), and charging can take place at centralized distribution centers, sometimes while the trucks are being loaded.

Curb management and land use: Finally, it’s worth noting that in cities, carefully considered curb and freight regulations can further reduce the impact of deliveries. New York City, for example, is incentivizing night deliveries (which reduce traffic and idling) and even building infrastructure to support the use of electric cargo bikes for “last mile” delivery.

Fighting for a freight system that works for everyone

You may notice that several of the programs and rules I describe above were only passed in the past few years. That speaks to a historical lack of urgency from government in addressing the harms of the freight system.

As Paulina Vaca of Center for Neighborhood Technology (one of the groups counting trucks in Chicago) told media last year, grassroots truck counts “weren’t taken seriously by the [Chicago] Department of Planning,” prompting advocates to contract with a professional traffic analysis firm which used cameras and computer analysis to produce “more systematic” research.

UCS has been proud to be part of Moving Forward Network and work with many of the local groups noted here to bring additional analysis into the conversation, increase the pressure, and ultimately win the rules, laws, grants, and commitments that can make the freight system cleaner and safer.

Several of these are already under attack by the Trump administration. The White House is attempting to roll back federal vehicle regulations and states’ ability to limit pollution from cars and trucks, it has ordered an illegal pause in federal funding that could delay or upend some of the programs described above. These come on top of direct attacks on immigrants and environmental justice programs, impacting many of the communities that bear the brunt of our freight system.

With our partners, we are defending against these attacks. And when it comes to transportation, we’ll be pointing out that states, local governments, and port districts retain a lot of power to clean up the ports, warehouses, and trucks that bring cargo from around the country and world to our homes and businesses. When led by experts within impacted communities, lawmakers and public agencies can take real action to address the harms of an expanding freight transportation system.