It has taken over 20 years, but EPA has finalized its next step in reducing pollution from new trucks. Unfortunately, it falls short of what states are already doing. On paper it may appear to align with aspects of the most stringent option considered by the agency in its proposal, but many of the finalized changes in enforcement and flexibility significantly undermine the effective stringency of the rule. One particularly notable adjustment reflects a direct request from truck manufacturers, who (as noted previously) have been intensely engaged in a battle to weaken the rule as part of an ongoing war against pollution regulations that undermines the lip service the companies give on climate.

Perhaps most importantly, this rule doesn’t even attempt to grapple with the question of how to eliminate emissions from trucks, focusing exclusively on fossil-fuel powered engines to the exclusion of electrification. In punting to next year a rulemaking that could electrify the freight sector, EPA has ignored the desperate requests of the communities currently burdened by freight pollution. While the rule finalized today will no doubt reduce emissions from the fossil-fuel-powered fleet in much of the country, it is a missed opportunity. This final rule will neither foster the adoption of any additional electric trucks nor will it match the stringency of the most advanced diesel emissions controls already required by state rules.

Bad news: electric trucks aren’t included in the rule

Let’s get this out of the way first: the only surefire way to eliminate freight pollution is to actually eliminate freight pollution. “Near zero” is a fossil fuel marketing buzzword, and with electric trucks on the market, EPA could have chosen to put the industry on an accelerated course to eliminate tailpipe pollution. Sadly, it didn’t.

Impacted communities have been quite clear that EPA must put the freight industry on a path to zero emissions. This rule was a clear opportunity to exercise the Agency’s authority under the Clean Air Act to promote the most advanced emissions reductions technology. Instead, EPA has finalized a rule exclusively addressing the emissions from heavy-duty engines, which means electric trucks are entirely omitted from the final rule.

Good news? Electric trucks aren’t included in the rule

EPA decided not to drive the deployment of the solution most needed by the community, which is a serious problem (that we hope they’ll address in the spring), but in the proposal they did something even worse: not only did EPA propose not to drive electrification through the rule, but they credited manufacturers for those electric trucks as well. If finalized, this would have led to the perverse problem that more electric trucks would lead to dirtier diesel trucks, a trade-off that public health cannot afford.

In the final rule, they have closed that loophole. It’s not much, but it was something we did ask them to do if they weren’t going to seriously consider electrification in this rule, so it’s good to see them follow through on that ask. Unfortunately, while they’ve closed this loophole, there are plenty more that made it through to the final rule.

Just the facts: EPA’s topline numbers fall short

The proposed rule was unique in my experience as a transportation/vehicle advocate: rather than propose a single, clear rule with one preferred option, EPA co-proposed two different rules (and everything in between). This means that the benefits of the final rule and how it compares to the proposal are extremely complicated to parse out—on the one hand, the Agency has strengthened critical aspects of the rule; on the other hand, the in-use tool used for enforcement opens the door to exploitation that could severely undermine the effectiveness of the final rule.

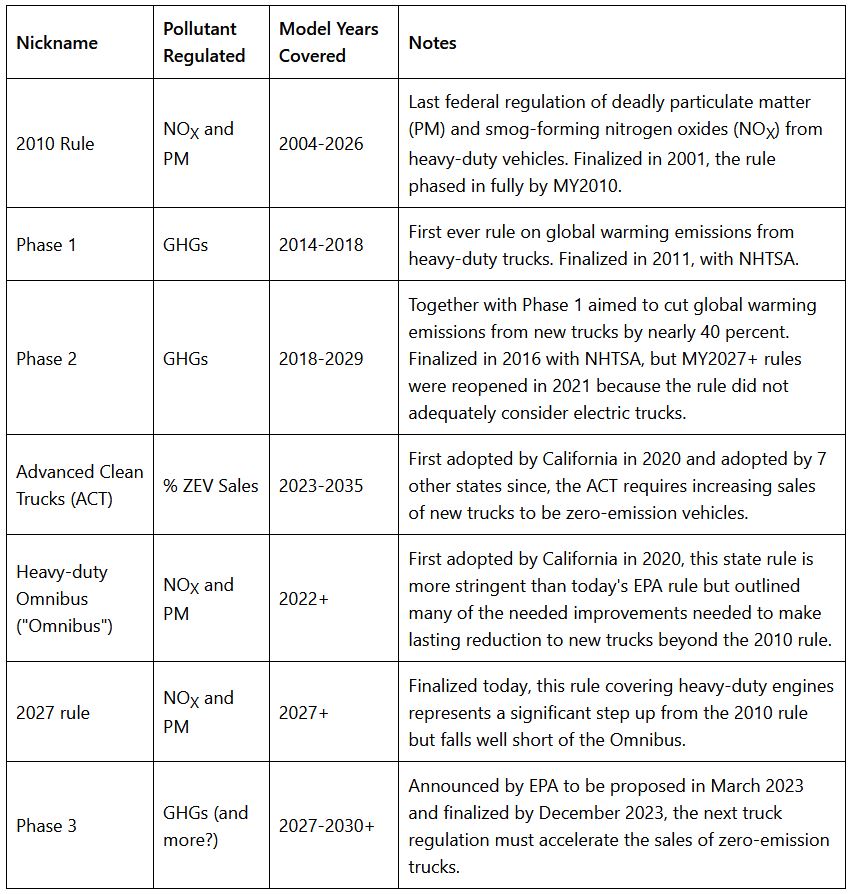

The most stringent option considered by EPA fell short of the state standards already on the books, but it mimicked the structure of the standard with a two-step procedure that, by 2031, largely aligned with the Omnibus regulations. Unfortunately, today EPA is largely just finalizing the first step of that rule, leaving a large gap between state leadership and federal action.

The new rule will require a 35 mg NOX/bhp-hr emissions on the current test procedure, compared to 200 mg NOX/bhp-hr for today’s new trucks, a reduction on paper of 82.5 percent. Improvements to the current warranty and useful life requirements increase the likelihood of those trucks achieving those emissions for longer—even though EPA only increased the warranty and useful life for Class 8 vehicles to 450,000 miles and 650,000 miles, respectively, short of the 600,000 miles and 800,000 miles required by the states, EPA at least finalized increases for Class 4-7 vehicles in line with what the states are already doing.

Another further improvement is reducing the level of pollution allowed from the dirtiest engines. Given the averaging nature of this program and its banking and crediting provisions, when a manufacturer produces a cleaner engine than required, they can sell a dirtier one. Under the proposal, a manufacturer could accrue enough credits to sell engines not much cleaner than those on the road today. Thankfully, they’ve reduced the maximum allowable limit to 65 mg NOX/bhp-hr, just less than double the average requirement, at least on the lab tests.

Unfortunately, loopholes in the in-use enforcement of these engines are likely to significantly increase the likely emissions from these engines compared to what these lab test requirements may require.

Déjà vu: loopholes remain, ready for manufacturers to exploit

No matter the lab test procedures, whether this action will yield the most effective emissions control technology and how well the rule reduces emissions in the real-world are dependent upon a test program and compliance margins that have been weakened considerably compared to the state regulations already on the books.

EPA already has experience with an inadequate in-use program—it’s one of the biggest reasons today’s emissions controls have not yielded the 90 percent reduction anticipated two decades ago. Though the consequences of this are well known, and I warned of this in advance of the final rule, EPA is opening a can of worms that could drastically loosen constraints on manufacturers for emissions performance under real-world driving conditions.

Even as it has become clearer and clearer from EPA’s testing at Southwest Research Institute that manufacturers can achieve a 90 percent reduction in NOX emissions on the current test procedure, truck manufacturers have spent millions of dollars in a host of lab tests to convince regulators that the rules are just too hard to achieve. The latest iteration of this is an echo of a strategy used over two decades ago to craft a loophole big enough to drive a polluting semi through.

In the last rulemaking on heavy-duty engine emissions of NOX, manufacturers were able to convince EPA to limit the data captured through the in-use program based on exhaust temperature. This loophole helped ensure that more than 90 percent of real-world data on trucks isn’t considered as a measure of emissions control effectiveness. Lo and behold, two decades of data have shown that unsurprisingly manufacturers didn’t care about operating conditions for which EPA absolved them of responsibility.

Unfortunately, today’s rule seems poised to repeat this error. Rather than just an outright exemption, EPA is proposing to add a temperature-based loophole on in-use emissions. This time, based on a very limited (and no doubt biased) dataset submitted by manufacturers well after the comment period closed, EPA is proposing an adjustment factor to in-use requirements based on the ambient conditions of the engine. Incredibly, that adjustment process starts kicking in below 77°F—hardly frigid temperatures—and excludes data below 40°F entirely.

The path that this opens up is extremely problematic—this adjustment factor scales with temperature and represents as much as a 60 percent increase in allowable emissions. While at extremely low temperatures there may be some argument for adjusting the requirements on manufacturers, giving truckers driving through Chicago or Denver a pass on their emissions because it’s a cold winter day is patently absurd—that’s real life, man, and the OEMs have to figure out how to reduce emissions across all conditions in which their trucks operate!

With nearly 8000 people estimated to die prematurely from exposure to truck pollution every year, creating another perverse incentive for manufacturers to ignore emissions in real-world conditions could prove deadly.

Tomorrow’s story: EPA’s next rule must drive electrification

From any angle, this rule falls short of both what is feasible and what is needed. But the good news is that there is another opportunity for EPA to make up for its miss today—EPA announced that it will propose new greenhouse gas emissions standards for trucks through at least 2030 (and we expect much longer). The Agency says a rule will be proposed by March 2023 and finalized by the end of 2023.

As it readies its next step, EPA still has not granted California its waiver for the Heavy-duty Omnibus and Advanced Clean Trucks rules. Especially with the federal government choosing to finalize weaker rules than what the states have shown is feasible and cost-effective, it is critical that the Agency at least get out of the way so these more stringent regulations can be enforced. The Clean Air Act is pretty clear on the question at hand, and the data is as clear as can be—California must get its waiver ASAP.

While the timetable is hopeful for getting something more done federally, EPA’s proposed two-step strategy risks prioritizing false solutions like the combustion of hydrogen derived from natural gas if it does not simultaneously account for both the greenhouse gas emissions and tailpipe emissions in its Phase 3 rule. To do this, EPA should make the forthcoming Phase 3 rule a multipollutant rule, just as it’s planning to do for passenger vehicles. We have the ability to simultaneously eliminate smog-forming, particulate (soot), and greenhouse gas emissions from all trucks—we need the certainty of a multipollutant rule to ensure we are working to do so.

This administration signed a global memo of understanding targeting the full electrification of the new truck fleet. Congress has provided a significant tailwind for the industry towards meeting that through incentives within the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as evidenced by a recent report showing new electric truck sales could exceed 40 percent in 2030 even in the absence of federal regulation. And manufacturers have committed to up to 60 percent of their new truck sales in 2030 being electric.

Regardless of how well today’s rule reduces diesel emissions moving forward, under its Clean Air Act obligation EPA must use the Phase 3 rulemaking next year to make sure industry lives up to its promises of a zero-emission future. We cannot afford another missed opportunity like today.