The EPA is getting ready to finalize a critical regulation limiting emissions of smog-forming nitrogen oxide (NOX) and soot (or particulate matter, PM2.5) from new heavy-duty trucks. This is the first time EPA has sought to limit emissions in over two decades, and it is long overdue.

Unfortunately, one of the reasons the regulations have failed has to do with how manufacturers’ compliance with those regulations plays out in the real world. With inadequate measures to curb on-road emissions compared to lab tests, EPA shifted the burden from manufacturers to the communities where those “flexibilities” in the regulation played out in the form of increased asthma, premature death, etc.

Many of the flaws in the last round of regulation have led to changes in the test procedures likely to be finalized by the end of 2022 to help tighten up the wiggle room granted to manufacturers. At the same time, the proposal hints at ways in which EPA could repeat past mistakes, which will create more lax standards than intended on paper and will lead to greater harm for the communities in which these trucks drive.

Below, I’ve tried to run through a few of the subtle ways in which EPA’s headline test cycle reductions could be undermined by loopholes granted to manufacturers, as we think about just how beneficial this next round of standards will be (e.g., do we really get a “90 percent reduction in NOX” just because the test procedure requirement drops from 0.2 to 0.02 g NOX/bhp-hr). And apologies in advance: this blog is weedsy.

Test cycles in the real world

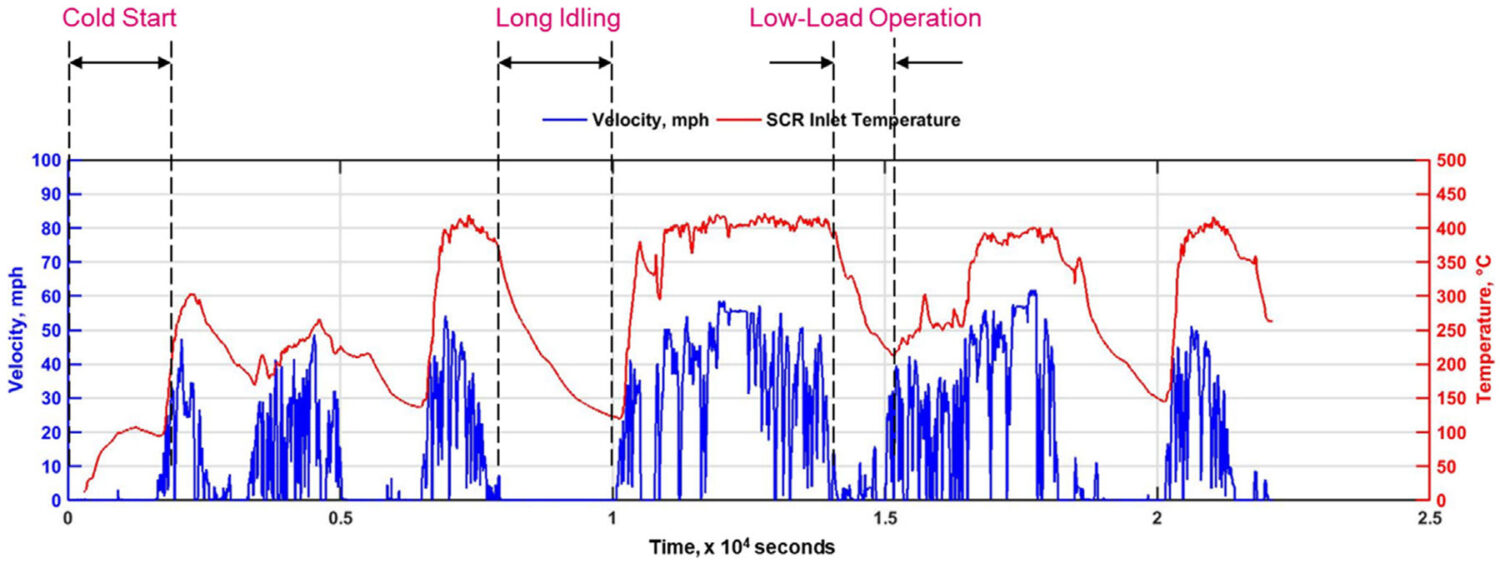

The current test procedures don’t consider operation at low speeds or under low loads, despite these being precisely the operating conditions around ports and warehouses, some of the areas worst impacted by freight pollution. As a result, emissions controls are virtually ineffective in these applications, harming the communities around freight corridors. As a result, we expect the final EPA rule to institute a new test cycle, the “low-load cycle”, which was already introduced as a result of state leadership on NOX regulations.

In-use performance and enforcement

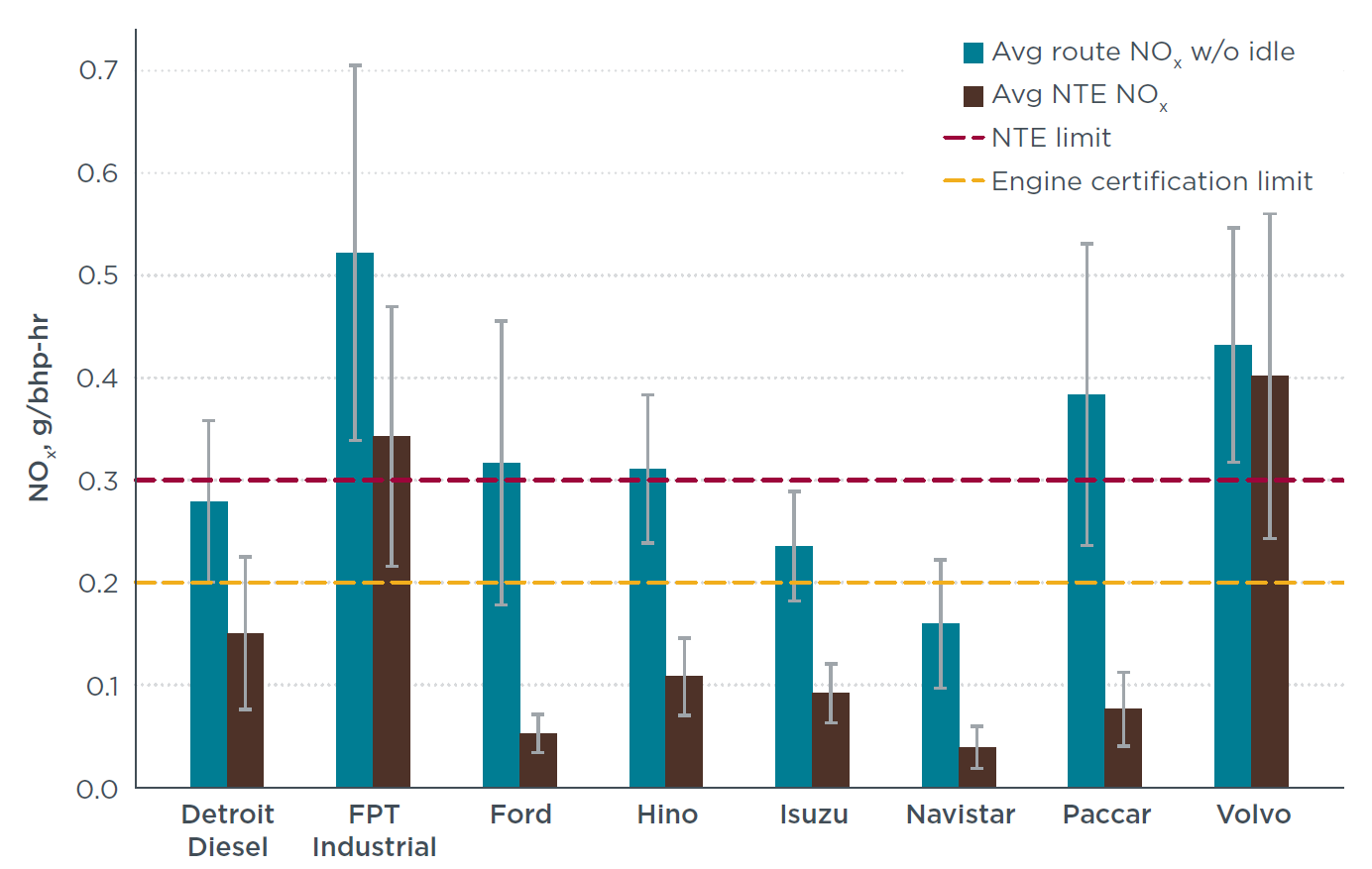

Another critical change being made to the program is related to in-use enforcement. Manufacturers are tested not just on the performance of their products on certification tests, but also on how those trucks perform in the real world. Currently, engines are “not to exceed” (NTE) 1.5 times the certified performance of engine. In this example, 1.5 is considered a conformity factor, meant to recognize that the test cycles are not perfectly reflective of all real-world conditions. However, not only are trucks today granted that extra 50% cushion in the real-world, but they are only required to fall below this NTE limit as long as the engine is operating under certain conditions.

Unfortunately, it turns out that these exemptions cover the vast majority of operating conditions experienced by trucks today—over 90 percent of all real-world data from EPA’s current in-use test program is thrown out! Across all of the data counted, manufacturers achieved a 0.18 g/bhp-hr standard, comparing favorably to the 0.20 g/bhp-hr standard. However, when looking at all the data, truck emissions were 0.42 g/bhp-hr, well above the allowable limit, even accounting for the conformity factor. The figure below shows clearly how much higher total emissions are when compared with the limited NTE data considered by EPA for compliance.

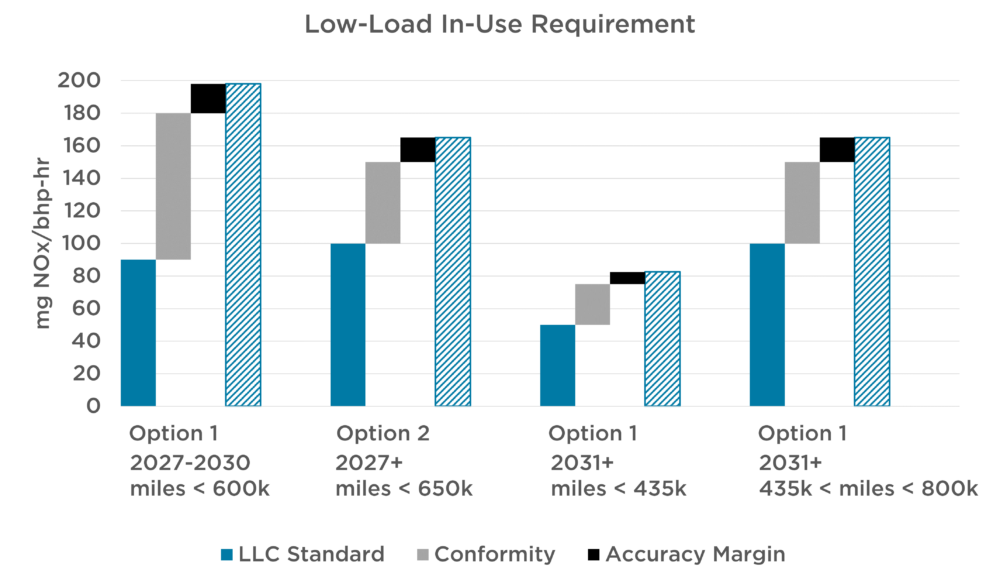

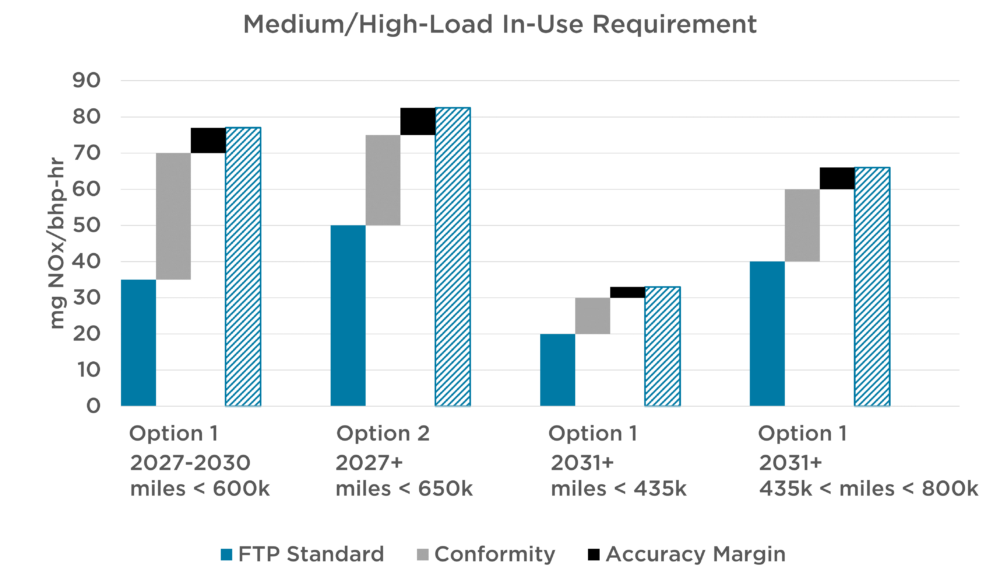

To close this gaping loophole in in-use requirements, EPA is expected to move forward with a program similar to California’s approach, where emissions data is broken down into time-averaged segments that are then compared to different test cycles (with a conformity factor) based on whether it is operating under high/low/idle operating conditions.

As UCS assesses how well this new in-use program closes loopholes being exploited by manufacturers, one thing we will be examining closely in the final rule is the conformity factor, i.e. the wiggle room granted to a manufacturer (it was 1.5 in the proposal), as well as the threshold limit above which non-compliance is determined (e.g., 10 percent, as proposed). It’s also important to look at how EPA is determining what tests to compare the real-world data to, as industry made a number of recommendations to EPA about how to make things easier on manufacturers. It’s especially important to see how these different allowances are compounded—given enough wiggle room, it’s easy for the most stringent requirement on paper be equivalent to the least stringent requirement for purposes of enforcement.

As an example of how these factors multiply, for example, a lab test that requires a standard of 20 mg NOX/bhp-hr but then has a conformity factor of 1.5 and an accuracy allowance of 10 percent would mean EPA wouldn’t be able to go after a manufacturer unless an engine emitted more than 33 mg NOX/bhp-hr—increase those to 2.0 and 15 percent, respectively, that increases to 46 mg NOX/bhp-hr. That’s potentially a 40 percent increase in real-world emissions with the same numerical standard. Similarly, as the figure above shows, there was not a substantial difference in stringency between the proposed Option 1 and Option 2 in terms of in-use emissions, with differences in conformity nullifying much of the difference in stringency, particularly in the early years of the program.

Finally, if we’ve learned anything from the current, inadequate in-use emissions program, it’s that exemptions to in-use testing must be severely limited. However, the truck manufacturers have responded to the proposal by pressing hard to exclude additional data from the in-use testing or use such data to erroneously increase the conformity factors used by EPA to govern in-use compliance, including around low temperature operations. When looking at the stringency of EPA’s rules, UCS and partners will certainly be looking at whether they’ve weakened their in-use testing programs to align more with industry’s requests.

Early/transitional credit programs

I’ve written previously about the danger credit programs pose to the stringency of the truck rule, and that continues to be a major concern as we look at the impact of the final rule. I recently wrote a (very wonky) paper about how giving credits to technology deployment in advance of the beginning of the rule in 2027 could pose a serious problem to the long-term effectiveness on the rule at driving the cleanest technology to market, but it’s worth summarizing here.

EPA has proposed three different early credit programs. The first was to reward the deployment of electric trucks—given that EPA has pushed its consideration of EVs in the greenhouse gas rule to next spring, this is not likely to be included in the final rule. The second program is the “Early Adoption Incentive” meant to credit the sale of trucks which mean a future standard. While a multiplier granted to these vehicles in the proposal would potentially erode some of the benefits of the rule for awarding credits incommensurate with the real-world benefits of the program, which could create issues, at least this credit program is limited only to the adoption of technology that EPA is attempting to drive through its rule. The third program for “Transitional Credits” is the one with most capable of significantly undermining the long-term trajectory of diesel emissions controls.

The Transitional Credit program allows manufacturers to earn credits for certifying engines under the new test procedures that go into effect in 2027, but such credits would be earned against today’s extremely weak, decades-old standard. Because EPA’s rules could require as much as a 90 percent reduction in emissions on the current test procedure, any credits earned against this weak standard could offset a very large number of trucks in the future.

While the illustrated example is simplified, more complex analysis shows that 1 truck certified to state requirements in 2024 could offset the harm of up to 7 of those trucks against the most stringent regulation considered in EPA’s proposal. Indefinite delay of more effective emissions technology could permanently impede the path towards cleaning up the diesel truck fleet.

Limits on mal-maintenance/tampering

As part of this NOX rule, EPA proposed significant increases in the warranty and required lifetime of emissions controls. Diesel trucks can be on the road for a million miles, but currently manufacturers are off the hook for any emissions control problems after the federal required warranty period of 100,000 miles. Some in the market are already purchasing extended warranties, but in order to ensure that diesel emissions controls remain properly maintained, more of the burden needs to be on the truck manufacturers to be responsible for the longevity of these systems. When the rule comes out, a point of interest will be whether the warranty and lifetime match that of the state rules, as EPA proposed in Option 1 (600,000-mile warranty and 800,000-mile useful life in 2031 and beyond), or whether they propose something much more modest, as requested by the Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association.

Another way to make sure that emissions controls are fully active and cannot be bypassed is to strengthen controls around on-board diagnostics and actually limit operation of a vehicle when the emissions controls are not functioning properly so that a vehicle operator must get the system to be compliant before driving it. These tools are known as inducements: they “induce” the driver to fix the truck. Some limited capability may be needed in order to get the vehicle to a shop safely, but EPA’s proposal included a wide range of overrides that would simply discourage truckers from addressing the faults in their control systems. Improper maintenance or tampering can lead to astronomical rates of emissions, so every inch of flexibility or deference to drivers around inducements can be extremely costly in terms of emissions and, as a result, public health. State regulations have strict inducements, so the degree to which EPA aligns with such parameters is important.

Truck loopholes will weaken the effectiveness of EPA’s regulations

No matter what the target may be for manufacturers on paper, all of the above nuances in how the NOX rule is administered have the potential to erode the long-term effectiveness of the forthcoming rule when it comes to reduction of harmful NOX emissions in the real world.

Any shortcomings in real world improvements in emissions translate directly into lives lost. With EPA likely punting to a future rulemaking accelerating the elimination of tailpipe pollution, it is critical that this step in clamping down on diesel emissions be as stringent as possible, since these vehicles will be on our roads for decades to come.