Today marks the 25th anniversary of the start of the most remarkable and rapid changes ever made in U.S. and Soviet/Russian nuclear posture and policy.

Susan Koch, who was director for defense policy and arms control on President George H. W. Bush’s National Security Council at the time, summed up what became known as the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs) this way:

President Bush’s first PNI announcement was unprecedented on several levels. First, in its scope and scale; it instituted deeper reductions in a wider range of nuclear weapons systems than had ever been done before. Second, the PNIs were primarily unilateral—not to be negotiated, but instead implemented immediately. While Soviet/Russian reciprocity was encouraged, it was not required for most of the U.S. measures. Third, the decisions announced on September 27, 1991, were prepared with a speed and secrecy that had never been seen before in arms reduction, and have yet to be duplicated. The PNIs were developed in just 3 weeks and involved very few people. In contrast, most arms control measures, before and after the PNIs, required months and often years of interagency and international debate and negotiation by scores of military and civilian officials.

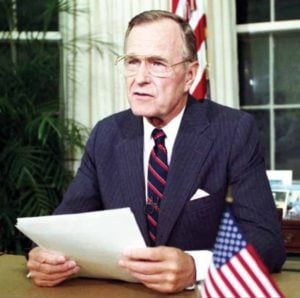

President Bush announcing his nuclear initiatives on September 27, 1991

In just four years, as a result of the PNIs and the 1991 START arms reduction agreement, the U.S. nuclear stockpile of active and inactive warheads dropped from 21,392 to 10,979, a reduction of almost 50 percent. Most of those cuts were due to the PNI-mandated elimination or sharp reductions in entire classes of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons.

Under the PNIs:

- U.S. ground-launched nuclear artillery shells and short-range ballistic missiles—around 2,100 weapons in total, most deployed in Europe—were withdrawn from the field and destroyed. (Note that is more than the current total number of U.S. or Russian deployed strategic weapons.)

- All tactical nuclear weapons on U.S. navy surface ships and attack submarines, and on land-based naval aircraft, were withdrawn from deployment. All of the nuclear depth bombs—approximately half of the total naval tactical nuclear stockpile—were destroyed; half of the other types were also destroyed.

- U.S. strategic bombers were de-alerted, the first time since 1957 that planes were not either in the air or on the ground, engines running and fully loaded with nuclear weapons. All Minuteman II missiles that were slated for elimination under the START agreement were rapidly removed from alert posture and scheduled for quick destruction, ahead of the treaty’s deadlines.

- A host of planned U.S. nuclear systems were cancelled, including a short-range air-to-surface missile, the mobile version of the 10-warhead long-range Peacekeeper missile and a small mobile long-range missile.

Just eight days after President Bush’s September 27 announcement, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev followed suit, declaring a range of similarly dramatic reductions in nuclear forces. The speed and reach of the Soviet leader’s response was far beyond what the Americans has expected. Only a few months later, after the Soviet Union collapsed, President Bush and newly elected Russian President Boris Yeltsin announced a second round of nuclear reductions. It was a cycle of reciprocal, unilateral steps to reduce the nuclear threat, unlike anything before or since.

Implications for Today

Twenty-five years later, what implications do the PNIs have for today?

Start with the most notable fact about the PNIs: they were unilateral steps taken at the president’s initiative. President Bush, joined by his national security advisor, decided to push for dramatic change and three weeks later he announced them from the White House. The president rejected negotiating an agreement with Russia or instigating a lengthy review by the Pentagon of options (although a review of nuclear war plans completed earlier in 1991 did provide useful background). Moreover, while President Bush clearly hoped for reciprocation from the Soviet Union, he decided to move forward with his plans regardless of whether Gorbachev responded or not.

Move to the current era, which began with President Obama early in his first term calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons and talking about putting an end to Cold War thinking. Yet he has not, or not yet, changed nuclear policy or posture in any deeply significant way. The successes, such as the New START arms control agreement, have been modest and in the more traditional arms control mode.

Now in the president’s final months, the White House is conducting a new review of possible nuclear policy changes. According to the press, some of the more significant changes, such as declaring that the United States would not be the first to use nuclear weapons, have already been rejected. Other options, like reducing U.S. deployed or reserve forces, may still be under consideration, but no decision has been announced.

What might hold President Obama back from following President Bush’s bold path?

One difference, opponents of nuclear reductions often point out, is the overall direction of the security landscape in 1991 versus today. Twenty-five years ago, the Soviet Union was collapsing. President Bush’s greatest worry was the possible loss of control of some of the nuclear weapons spread across four Soviet republics. That concern was perhaps the primary motivation behind the PNIs.

Today, Russia is no longer the same conventional threat to Europe that the Soviet Union was, but under Vladimir Putin’s leadership it has become an international bad actor, while maintaining a nuclear arsenal that is the only threat to the survival of the United States.

But it is that last of these factors that should provide all the motivation President Obama needs to act boldly. It is a simple truth that nuclear weapons are no longer a security asset for the United States, but a liability. The only role for U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter a nuclear attack on the United States and its allies. And in 2013, based on the Pentagon’s analysis, President Obama concluded that the United States could safely cut its nuclear stockpile by another one-third, to roughly 1,000 deployed long-range nuclear weapons, regardless of what Russia did.

To date, the president has not acted on this conclusion, instead waiting for Russia to agree to further reductions. But, following the model of his predecessor, President Obama should act boldly and quickly, reducing U.S. strategic weapons to 1,000 deployed warheads. He should also remove land-based nuclear-armed missiles from hair-trigger alert, which would significantly reduce the likelihood that a U.S. nuclear weapon will be used by mistake.

And he should take these steps even if he does not have a willing partner in Putin. Showing leadership on the nuclear issue will further isolate Russia in the international community, while freeing up resources and energy to devote to more important security concerns. President Bush decided to make changes in U.S. nuclear forces and posture without requiring a Soviet response because they were in U.S. security interests regardless of whether Russia reciprocated. That is as true today as it was 25 years ago.